Ffasâd y Vulcan

, 16 Ebrill 2020

Cofrestrwyd tafarn y Vulcan fel ‘ale house’ am y tro cyntaf ym 1853. Erbyn iddi gael ei datgymalu gan yr Amgueddfa yn 2012 gwelwyd sawl cyfnod o addasiadau. Roedd gwaith addasu 1901 ac 1914 mor sylweddol fel bod rhaid ceisio am ganiatâd cynllunio drwy Gyngor y Sir. Heddiw, mae’r cynlluniau yn Archifdy Morgannwg.

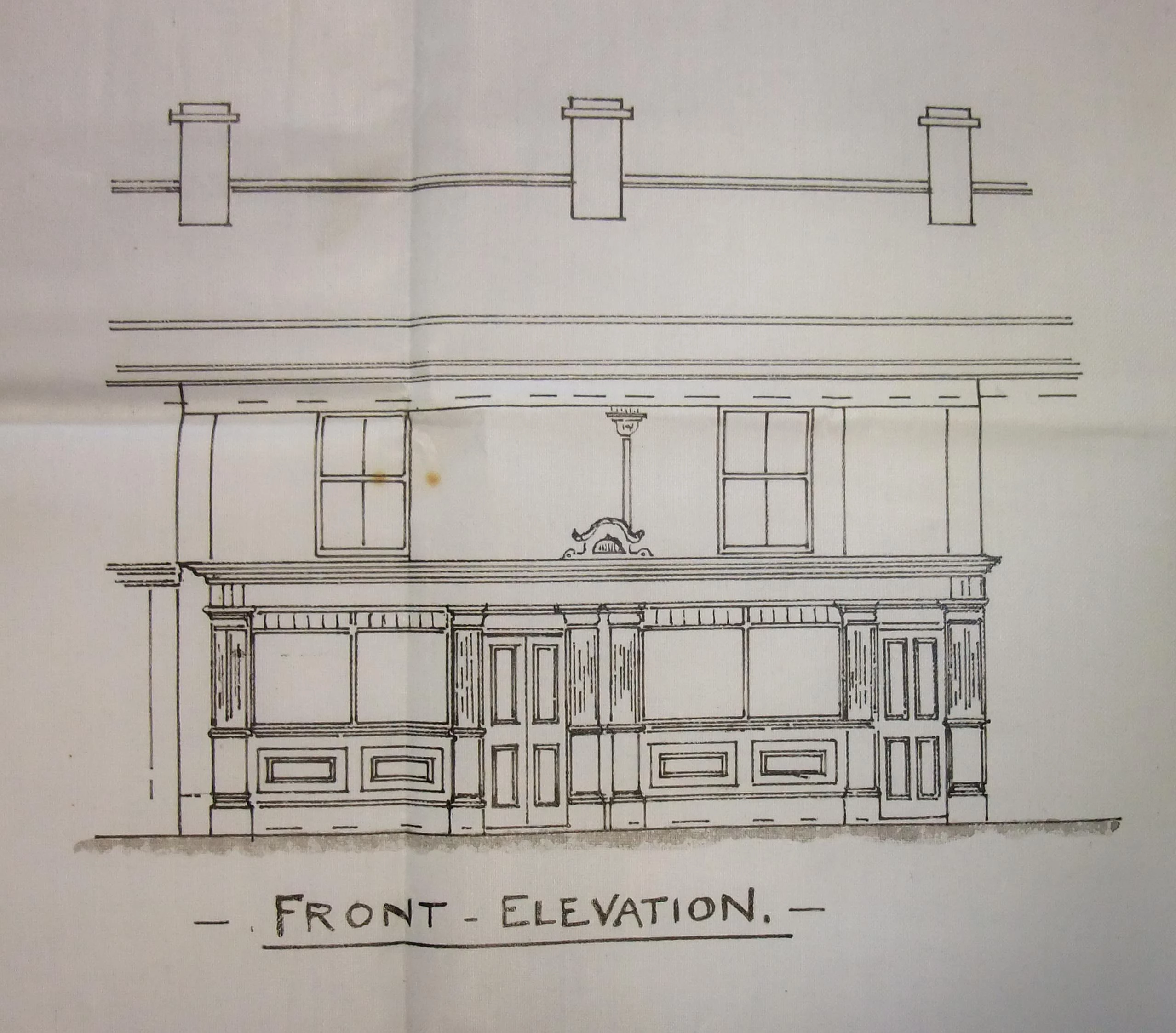

Mae’r cais cynllunio o 1914 yn cynnwys dau ddarlun (does dim darlun o’r ffasâd ar y cais o 1901) – labelwyd un darlun yn At present, a labelwyd y llall yn Proposed. Does dim esboniad ysgrifenedig wedi goroesi i gyd-fynd â’r darluniau. Serch hynny, wrth edrych yn fanwl mae modd bwrw mwy o olau ar y newidiadau arfaethedig. Y gwahaniaeth mwyaf amlwg yw’r cynnydd ar y llawr cyntaf o ddwy ffenest i bedair, a chodi pileri newydd o frics coch naill ochr. Gwaredwyd y parapet oedd o flaen y to – sydd i’w weld fel cyfres o linellau llorweddol uwchben y ffenestri, ac fe addaswyd y simneiau a gosodwyd to newydd o lechi. Bu un newid arall, sydd ddim yn amlwg yn y darlun, a hwn oedd y newid mwyaf yn hanes y Vulcan – cynyddwyd uchder yr adeilad yn sylweddol. Mae’r darlun gwreiddiol yn dangos y dafarn yn rhannu to gyda’i gymdogion, lle mae’r darlun arfaethedig yn dangos adeilad cryn dipyn yn dalach na’r cymdogion.

Doedd dim bwriad i newid strwythur y ffasâd llawr gwaelod – dau ddrws, a dwy ffenest wedi eu rhannu yn ddwy a ffenestri linter (fanlights) uwch eu pen. Ond, wrth edrych yn fanwl mae modd gweld bod nifer o wahaniaethau allweddol, a digon i awgrymu fod y ddau ffasâd yn rhai gwahanol. Yn y darlun gwreiddiol mae dau banel hirsgwar o dan bob ffenest, ond yn y darlun arfaethedig dim ond un sydd. Mae’r nifer o baneli drws yn wahanol hefyd. Yn y darlun gwreiddiol, naill ochr i’r ffenestri mae’r pileri yn rhai rhychiog ac yn gorffen cyn cyrraedd y ffris. Dyw’r pileri ddim yn rhychiog yn y darlun arfaethedig ac maent yn cario ymlaen mewn i’r ffris nes cyrraedd y cornis uwch ei ben. Mae’r darlun arfaethedig hefyd yn dangos tri ffenest linter uwch ben pob gwydr ffenest, lle mae saith yn y darlun gwreiddiol. Dyw’r terfyniad addurniadol ddim i’w weld yn y darlun arfaethedig chwaith. Dim ond yn y darlun arfaethedig mae’r gwahaniaeth mwyaf oll i’w weld, sef yr arysgrif newydd THE VULCAN HOTEL, WINES & SPIRITS ac ALES & STOUTS.

Er nad yw’n glir yn y cynlluniau, rydym yn sicr fod y darlun gwreiddiol yn dangos ffasâd llawr gwaelod o bren – tebyg iawn i flaen siop Fictoraidd draddodiadol, a newidiwyd hwn yn 1914 am un tebyg o deils gwydrog a arhosodd yn eu lle nes tynnu’r adeilad yn 2012.