Museums and Dust

, 4 Mawrth 2015

Dust, dust, dust, where ever you look! Museums are dusty places - dust is on top of shelves and underneath cupboards, it covers objects, books, specimens... Keeping our heritage in tip-top condition is a constant battle against dust.

What is dust? Dust in the atmosphere is made up of lots of tiny particles of soil, pollen, pollution, volcanic eruptions etc. Inside buildings, such as museums and your own office or home, dust is mainly bits of human (and pet) hair and skin, textile and paper fibres.

Why is dust a problem? Fresh dust, in small amounts, is not a problem other than making objects look unsightly. Over time, however, dust has a tendency to become really sticky. How often do you clean the tops of your kitchen cupboards? Only when you move houses, like most people? Then you'll know how difficult it is to remove the dust.

In addition, dust it hygroscopic - it absorbs moisture from the air. And because dust is really nutritious - just think of all those yummy skin cells - once it gets damp it is the PERFECT substrate for mould. Mould is really bad. Mould is responsible for damage to an awful lot of museum objects across the world.

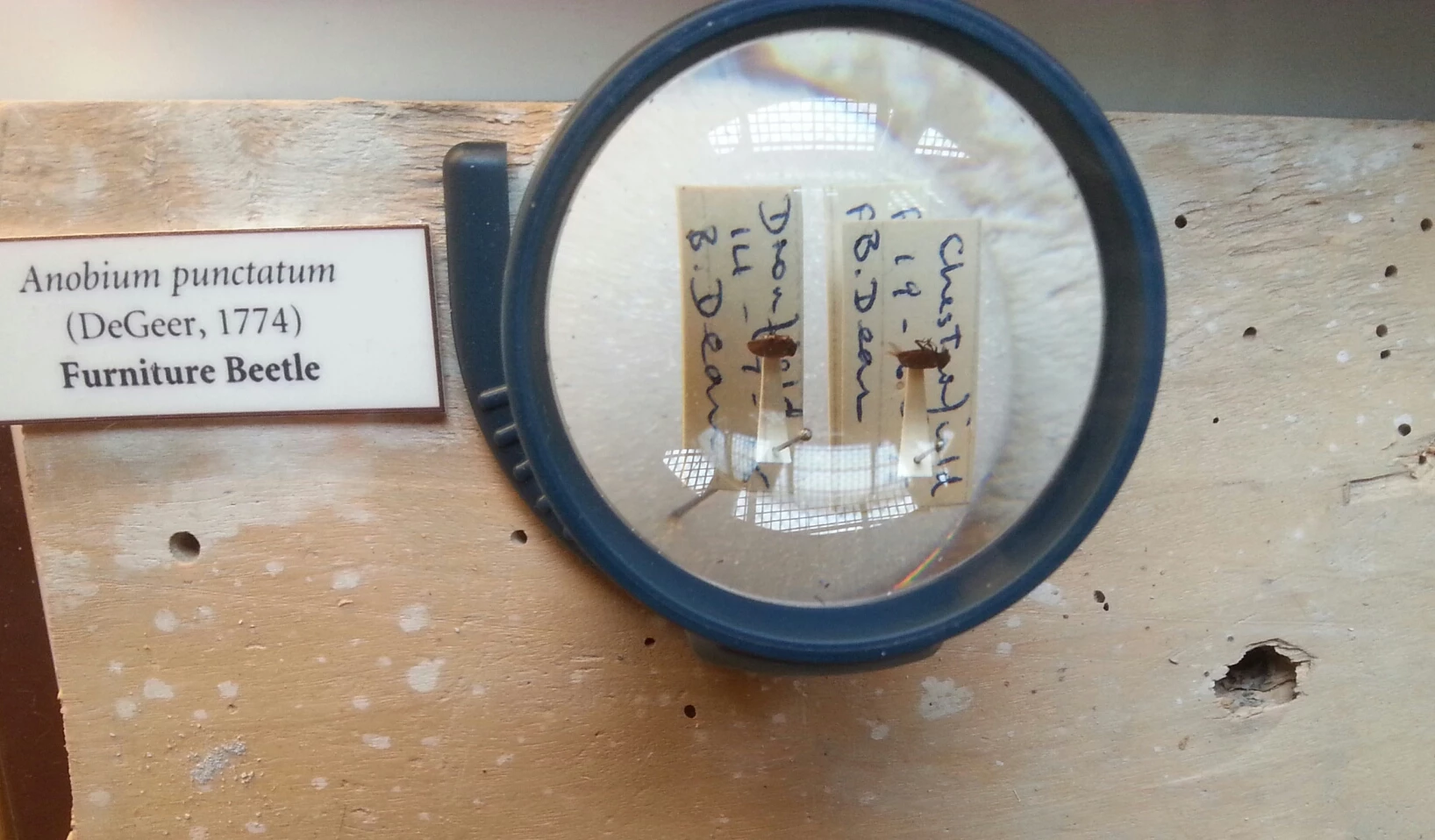

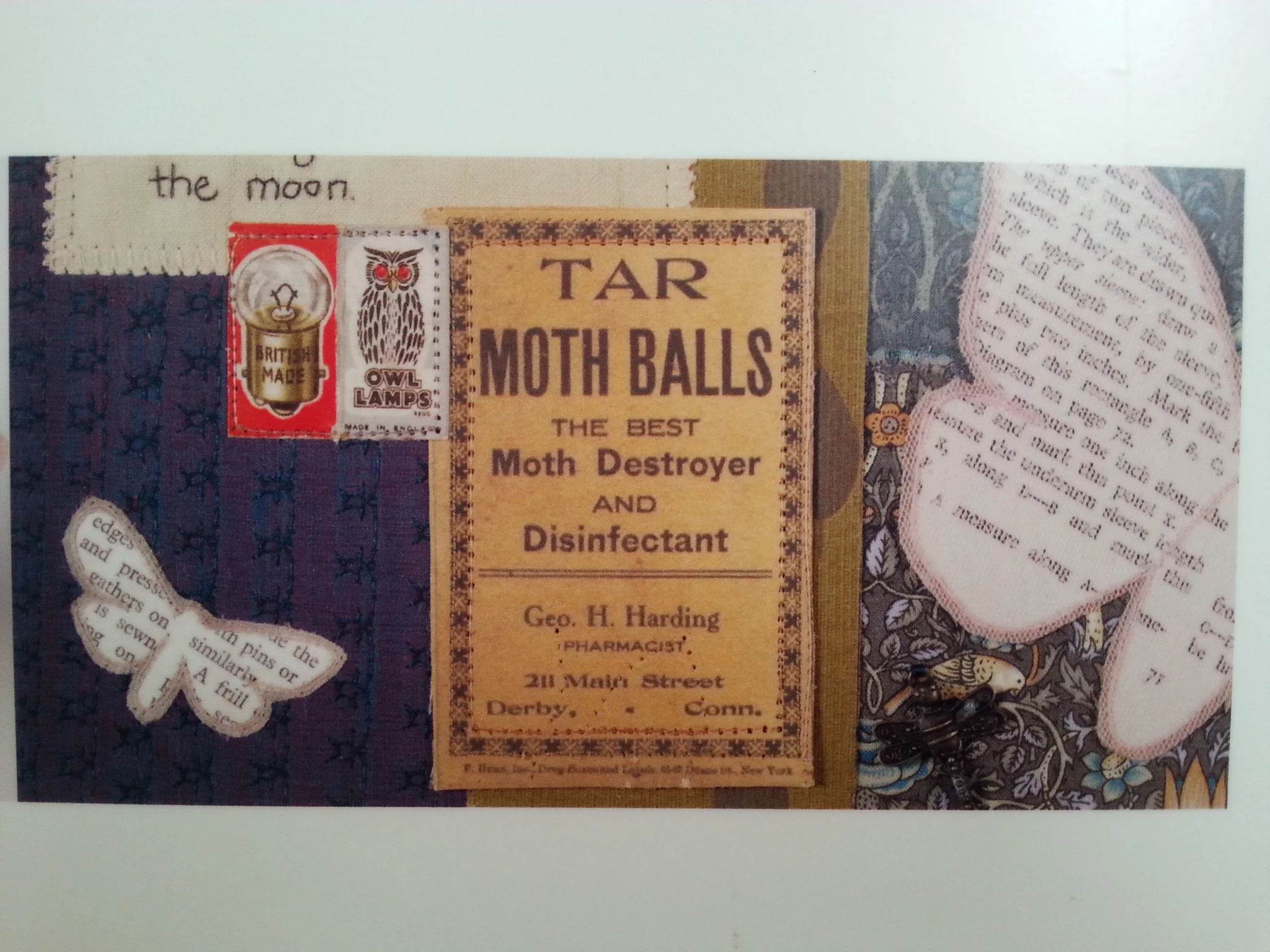

Dust also attracts pest insects. They hide in dust, sometimes live of it – or the mould that grows on dust – and generally thrive in environments that are dusty, messy and neglected. There are some insects that cause a lot of damage to museum collections.

So we keep dust at bay in the museum because we want to maintain your heritage in as good a condition as possible. We are fortunate to have the support of some brilliant volunteers to help us keep the collections clean. Rachel, Vicky, Meredith and Elizabete - all students at Cardiff University's Department of Archaeology and Conservation - have just helped us clean one of the Library stores and one of the Art stores. Thank you to the volunteers for their help keeping dust, mould and insects under control in the museum.