Gifts of the Welsh Gold King

, 27 Tachwedd 2019

Often, when writing a book on one subject, you come across fascinating information which cannot be included because it strays too far from the original remit. Such was the case when writing The Curious Case of the Eisteddfod Baton (Wordcatcher Publishing) a fascinating story about a Welsh gold conductor’s baton, housed at Parc Howard Museum, Llanelli. The baton had was given to the National Eisteddfod by William Pritchard Morgan, the ‘Gold King of Wales’ who had given other gifts of Welsh gold, including two now in Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

The Welsh Gold King

In 1888 William Pritchard Morgan was enjoying mass popularity and success. The millionaire ‘King’ had come a long way from his modest origins at Usk in 1844 where he was born, the son of William Morgan, an influential Wesleyan preacher. They were not rich, the family house consisted of just a back parlour, kitchen with pantry, and three bedrooms for the six family members and a servant. When Morgan was eight his father died from a chill caught while tramping around the country preaching - his will included old carpets and pans, an old piano, about twenty books, a German clock but nothing of silver or gold, and no money. The assessor valued his possessions at just £84 when the average yearly wage for a teacher was around £81.

As soon as he was old enough Morgan was articled to work for Newport lawyer Robert James Cathcart but he did not stay to complete his articles. Apparently he and Cathcart had a ‘lively quarrel’ when Morgan had taken exception to something Cathcart had said to him. Without further ado young Morgan put on his hat and took himself off, but worried about the reception he would receive at home for abandoning his job he decided instead to run away to Australia.

Having sold his watch and law books Morgan proceeded to Liverpool where he embarked for Australia and new opportunities offered by the second largest gold rush in the world – the first having been in California a decade previously.

Some twenty years later Morgan was back in Wales - now a multimillionaire through his enormously successful legal practice and investments in gold mines. Fascinated by the myriad reports that gold had been found in Wales he bought a mansion on a mountain in Dolgellau - and began digging.

He was not the first to have done so. The Little Gold Rush of North Wales in the 1860s saw huge amounts of money made and lost, all widely reported in the British and colonial press. Morgan, along with half the world, avidly followed the developments until the small gold rush petered out at the end of the decade.

Convinced he could succeed where others had failed Morgan, by force of both his personality and his money, set about transforming the mining of gold in Wales. Shortly after taking over the Gwynfynydd mine in Dolgellau in 1887 Morgan’s faith was vindicated when he hit a large pocket of gold. So fabulous was this discovery that he declared to the whole of Britain there was enough gold in Wales to pay off the national debt. His mine, he said, was going be one of the richest in the world - and as there were fifty other sites in North Wales there was every reason to believe that gold would be found in huge quantities. ‘Gallant Little Wales’ was going to be enormously wealthy.

Morgan’s announcements sent the national press into frenzy. Story after story appeared and every development at Gwynfynydd was enthusiastically reported which in turn brought any array of visitors, from royalty to hordes of sailors who hiked up the mountain on their days off. Morgan became a celebrity and with his new found fame pursued his passion for politics, controversially being elected MP for Merthyr - a huge endorsement of his liberal beliefs and his fight for working class people.

As a celebrity and politician Morgan loved to use his gold. He had specially commissioned pieces presented to leading figures of the day, such as ‘A History and Geography of Wales for the Young’ bound in gold for The Princess of Wales; a paperweight made of a solid piece of gold ore for the Prince of Wales; and a medal and a gold covered album of pictures of Corwen presented to Queen Victoria, commemorating her 1889 visit to Wales. While the whereabouts of these objects are unknown, three of Morgan’s gifts are in Welsh museums: the Eisteddfod baton at Parc Howard, Llanelli (for more on this see The Curious Case of the Eisteddfod Baton (Wordcatcher Publishing)); the Stanley Medal; and the Clara Novello Davies’ baton both – the last two now housed at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

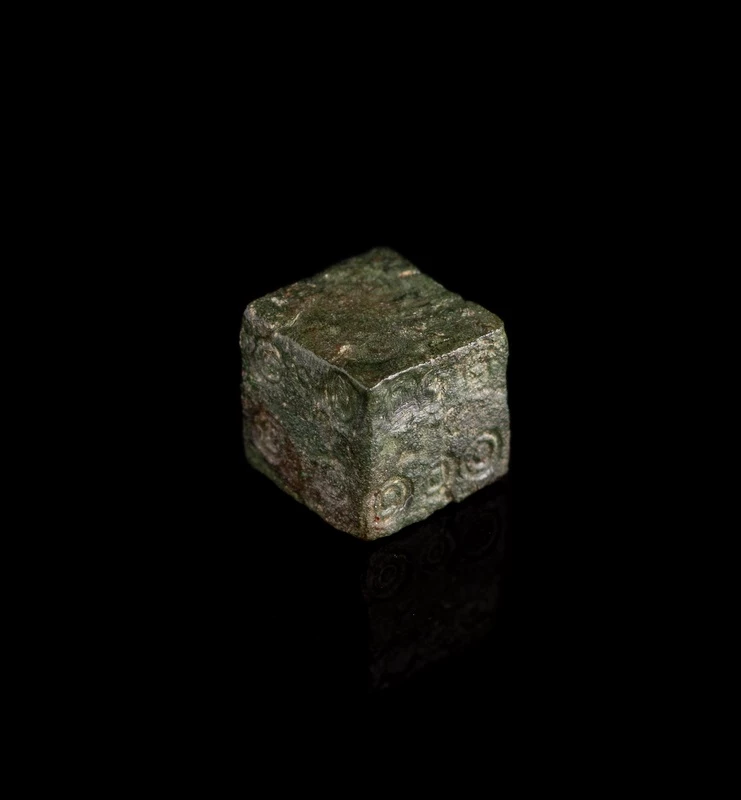

The Stanley Medal

The Royal Geographical Society’s (RGS) most prestigious award is a gold medal and two are awarded every year, each requiring the approval of the Queen. In 1873 they had presented one to Henry Morton Stanley for finding Dr Livingston; but seventeen years later Stanley carried out an act so universally acknowledged as pure heroism, that the Society wanted to honour him again. However, they had already given him their highest award so what were they to do? In the end they gave him a second gold ‘unofficial’ medal – which is why it does not appear in their annual record of awards.

In 1890, five years after the killing of General Gordon in the revolt against British rule in Egypt, Emin Pasha, then the Governor of Egyptian Sudan, had become trapped during an outbreak of fighting and his plight became world news. It was Stanley who led the controversial Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1886-89), one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa, where he succeeded in rescuing Pasha. It was in recognition of this bravery that the medal was commissioned - and having sought the advice of the Medal Department of the British Museum the design was entrusted to Elinor Halle.[1]

Elinor Hallé (1856-1926) was a sculptor, inventor and daughter of the conductor and founder of the Hallé Orchestra. She had been a student at London’s Slade School of Art, which in 1871 was the first public art school to admit women on the same terms as men. She had been one of the Slade Girls - a group of women ‘responsible for a large number of the cast medals produced during the revival in Britain in the 1880s and 1890s … now shadowy figures about whom little is known.’[2]

At the time of commission for the Stanley honour, Elinor was a respected medal designer and her medal of Cardinal Newman had won top prize at the 1885 International Inventions Exhibition.