Dyes and Tannins in the Amgueddfa Cymru Botany Collections

, 4 Mawrth 2019

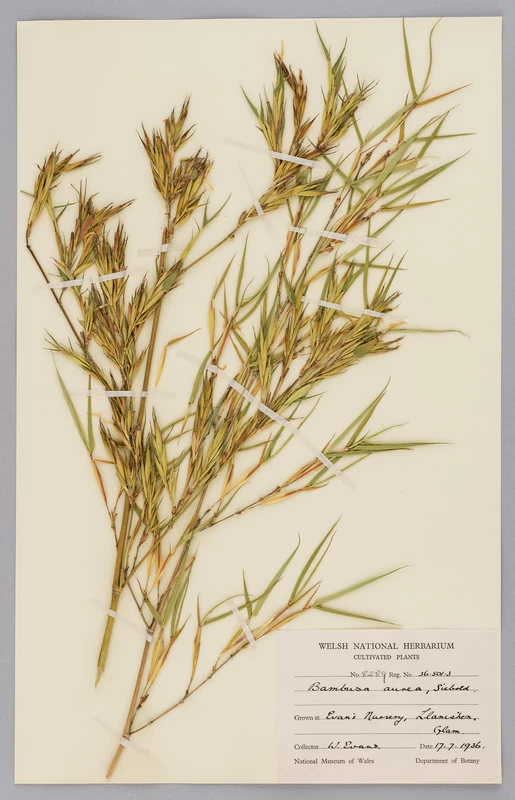

The Amgueddfa Cymru economic botany collection features 65 specimens of plant-based dyes and tannins. The collection includes a range of leaves, roots, petals, seeds and barks used for dyeing and tanning from around the world.

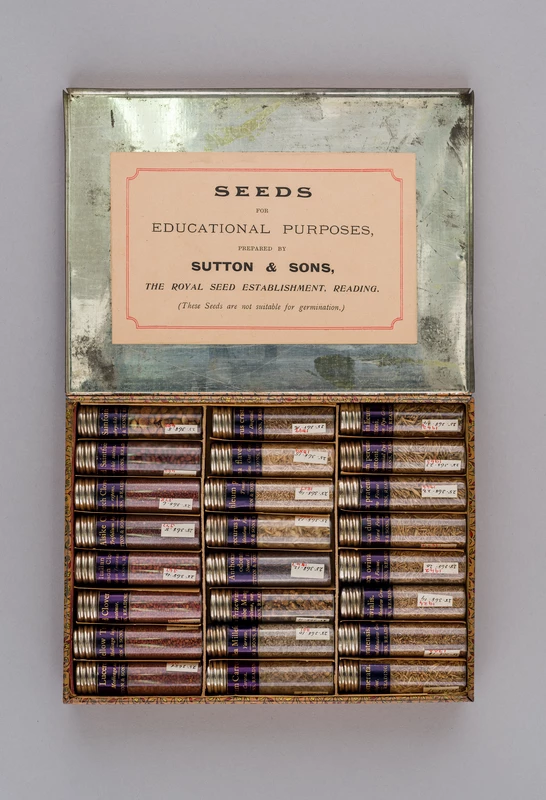

'Economic Botany' refers to a group of plants that have recognised societal benefit. The Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales economic botany collection contains over 5,500 plant-based specimens, together with 12,000 timber specimens. Categories within the collection include medicinal plants; food products; dyes and tannins; gums, resins and fibres; and seeds.

Most of the dye specimens were collected from Asia, South Africa and the West Indies as well as a few samples from South America. There is one specimen from the UK - Isatis tinctoria (Woad) from Roath Park Cardiff (1936). Most of the acquisitions of these specimens were made in 1914, 1920—22 and 1938. Only two of the specimens were added after 1938.

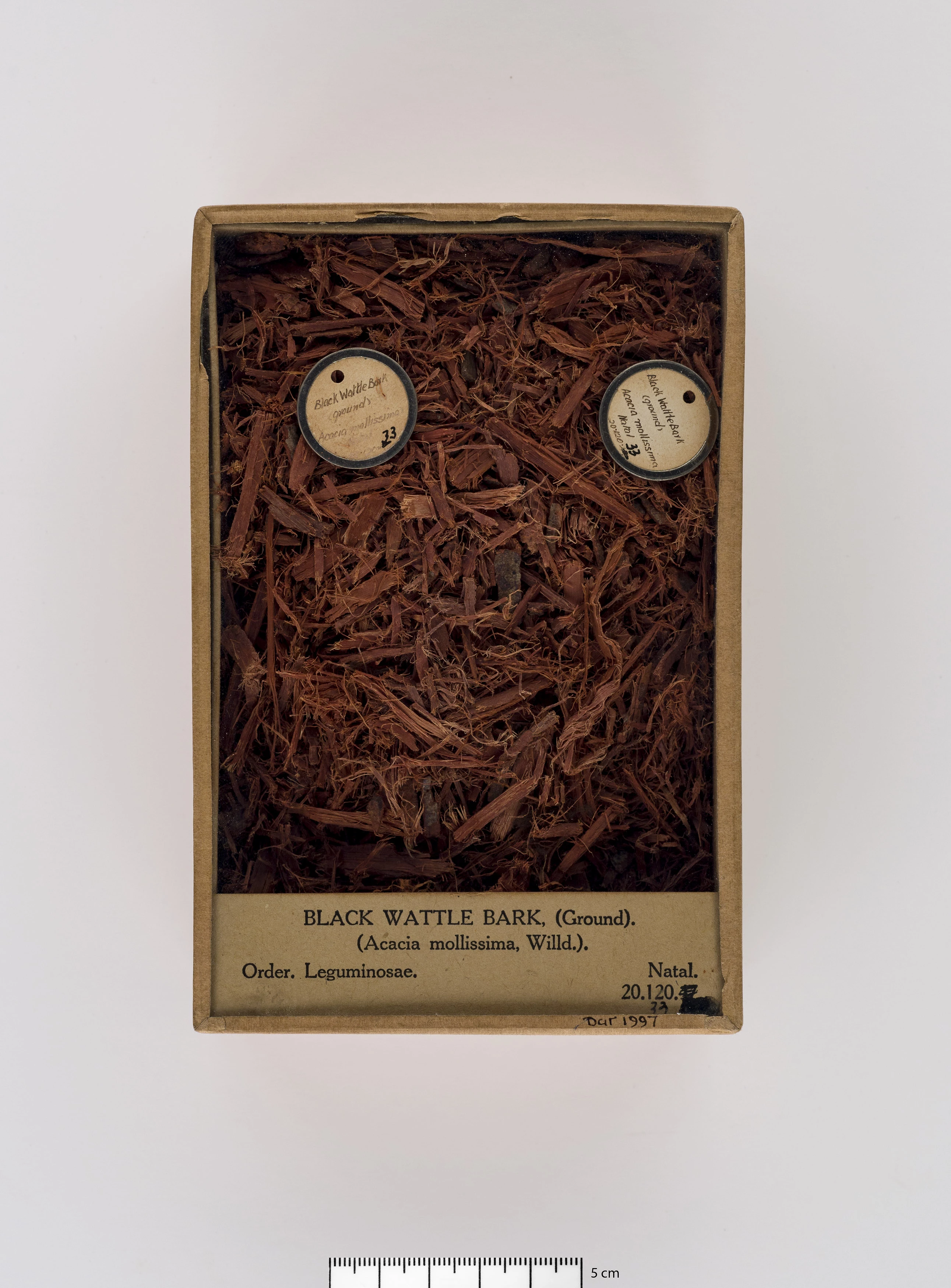

As well as leaves, petals, roots and fruits the collection contains a range of specimens of barks for dyeing, largely acquired in the 1920s.

Dye specimens

A number of the plant-based dye specimens originate from India including:

- The dried leaves of Indigofera tinctoria (Indigo) – one of the most famous plant dyes produces a range of blue tones.

- The roots of Rubia cordifolia (Indian madder) which produce a red dye.

- The roots of Morinda citrifolia (Al dye) which produce a yellowish colour.

- Myrobalans fruits (Terminalia chebula) which produce a yellow dye.

- The petals of Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius).

Many of these plants indicate their potential as colouring agents in their botanical names. Carthamus derives from Arabic meaning ‘dye’ whilst tinctoria is a Latin word for dyeing or staining.

The collection also includes specimens from the Caribbean including Bixa orellana (Anatto seeds) from the Dominican Republic, Gold Coast, Trinidad and Tobago; and Bursera graveolens leaves from Colombia, both of which produce a red dye.

Some of these plants are used in combination to produce enhanced tones. For example, Myrobalans (Terminalia chebula) produce a buttery yellow on their own, if added to Indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) produce a teal and with madder (Rubia cordifolia) they produce orange.

Tannins

Some barks are very high in tannin. Such barks are useful for the dyeing of cellulose fibres (such as cotton and silk). The collection features a range of barks used as tannins including:

- The powdered bark of Quercus tinctoria (North America 1921), known as Dyer’s oak.

- Haematoxylon campechianum (Log wood) (Central America and West Indies 1921) which produces a purple from the heartwood.

- Rhizophora mucronata (Mangrove) (India 1920) bark which produces a reddish brown with mordant.

- The bark of Ceriops candolleana (Tengah) (India 1920), used in Malaya within Batik dyeing for purple, brown and black colours.

- Cassia auriculata (Tanner’s Cassia) (India 1921).

- An extract of wood from Schinopsis balansae (Quebrachio) from Argentina.

- Acacia mollissima (Black Wattle) (South Africa) including bark, chopped bark, ground bark and solid mimosa extract (acquired from Kew in 1924).

The collection also includes a range of Libidibia coriaria (Divi divi) seed pods from the West Indies used for tanning and extract as dye (including specimens acquired from Kew in 1924).

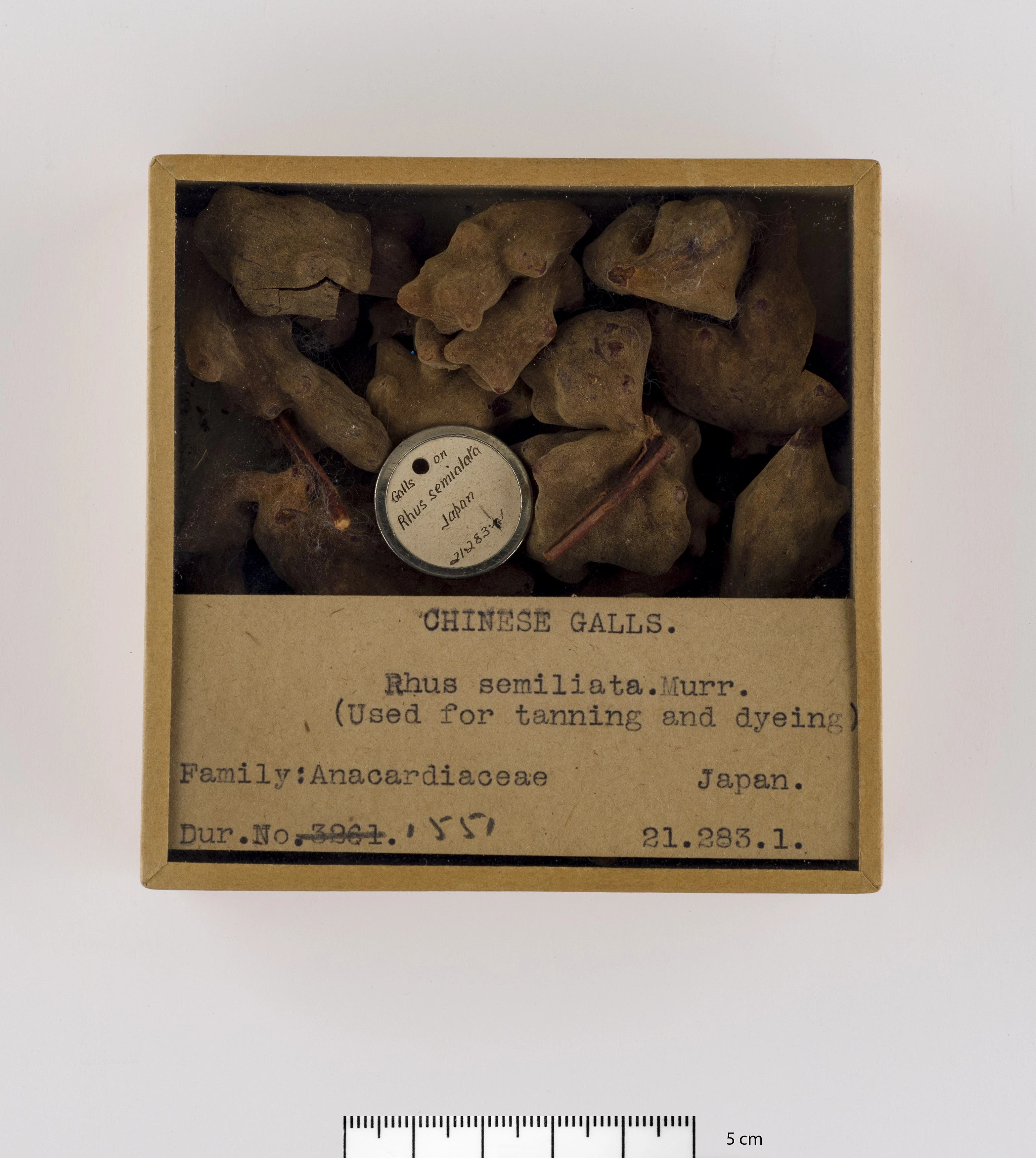

Galls

The collection also contains a range of galls mainly from Southern Europe (used as tannin) mainly acquired in 1914. This includes Blue Aleppo Galls, Green Aleppo Galls, Morea galls (Greece), White Bussorah galls, Blue Smyrna galls. These oak marble galls are caused by gall wasps which puncture bark of Quercus species and lay eggs inside. As well as oak marble galls, Chinese Sumac (Rhus chinensis) are also used as tanning agents.

Galls are used in dyeing processes since they tend to be very high in tannin. Cellulose-based fabrics are often treated in a gall bath prior to adding mordant (a substance that fixes dye in fabric). This process is called ‘galling’. The fabric can then be mordanted with alum, as the tannin forms an insoluble compound with the alum and natural dye, resulting in more permanent colour.

Dyed wool specimens

The dyes and tannins collection also features a range of specimens of wool that were dyed with plants using wool from the Cambrian Mill, Felindre. This includes Weld (with tin mordant), Privet (with tin mordant), Brazil wood (with alum mordant), Onions (with tin mordant), Eucalyptus (with copper mordant), Indigo (no mordant), Madder (with tin mordant), Walnut (no mordant) alongside two red and blue cloth specimens (possibly Madder and Indigo).

Tin can produce very bright natural colours. However, in excess it can make wool brittle and it is also harmful, potentially causing irritation to skin, eyes and respiratory system and damage to the liver and kidney system. Of note are the two specimens (Walnut and Indigo) that are ‘substantive’ rather than ‘fugitive’. Substantive dyes do not require a mordant.

In 2017-2018 Poppy Nicol worked with Heather Pardoe to explore the economic botany collection and its relevance for helping us understand biodiversity and the importance of plants for health and well-being. You can read more about the Sharing Stories Sharing Collections Project here.

Have a look back at previous posts about this collection:

This article is by Dr. Poppy Nicol, a visiting researcher from Cardiff University.