Y Cenhedloedd Unedig yn nodi blwyddyn ryngwladol tabl cyfnodol yr elfennau cemegol: Chwefror - manganîs

, 8 Chwefror 2019

Rydym wedi dewis manganîs i sôn amdano ym mis Chwefror fel rhan o flwyddyn ryngwladol tabl cyfnodol yr elfennau cemegol. Efallai nad yw manganîs yn un o’r elfennau sy’n neidio i’r meddwl wrth sôn am Gymru ond mae’n bwysig iawn i Gymru ac, yn wir, i Ynysoedd Prydain.

Pan fydd yn ymddangos yn naturiol, mae’r elfen fetelig manganîs (symbol cemegol – Mn, rhif atomig 25), bob amser yn digwydd mewn cyfuniad ag elfennau eraill yn yr hyn a elwir gan wyddonwyr yn ‘gyfansoddion’.

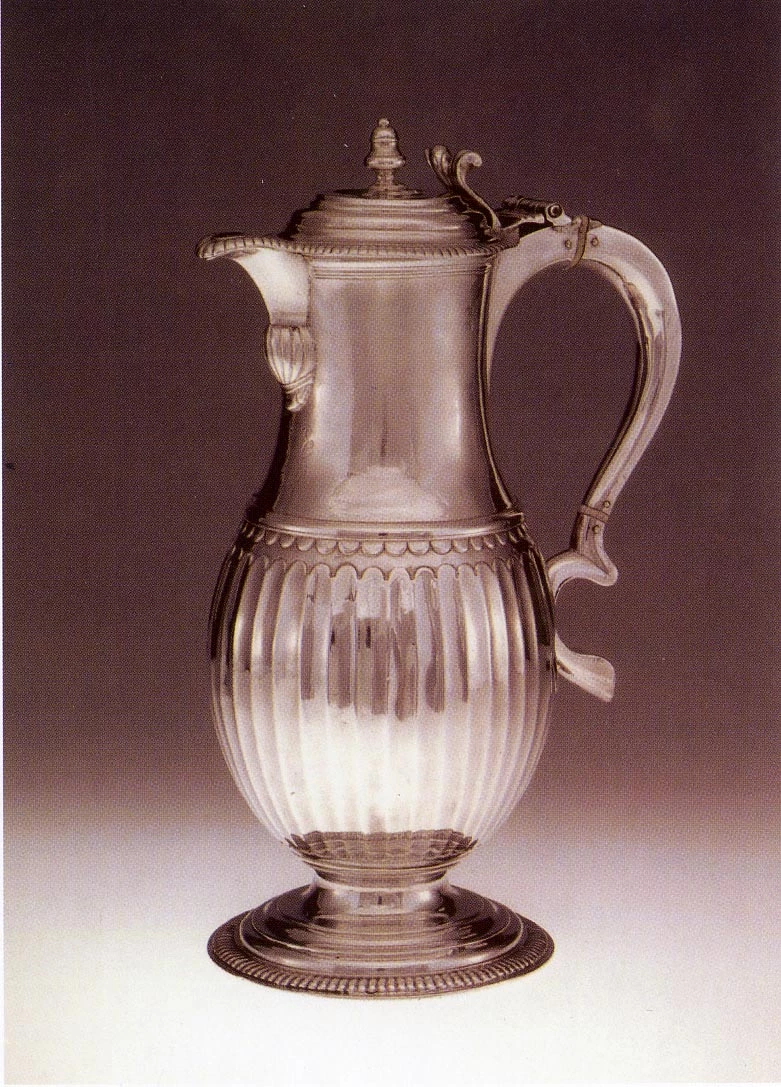

Ymhell cyn y flwyddyn 1774, pan gafodd metel manganîs pur ei arunigo gyntaf a’i gydnabod yn elfen newydd gan y cemegydd o Sweden, Johan Gottlieb Gahn, gwelwyd bod cyfansoddion oedd yn cynnwys manganîs yn ddefnyddiol iawn mewn prosesau diwydiannol. Yn wir, gwyddom fod hen wareiddiadau fel yr Eifftiaid a’r Rhufeiniaid wedi defnyddio manganîs deuocsid i dynnu lliw o wydr.

Yng Nghymru, mae ocsidau manganîs yn digwydd mewn nifer o wahanol gefndiroedd daearegol ond ni ddechreuwyd cloddio amdanynt tan ddechrau'r 19eg ganrif pan ddaeth y dyddodion a oedd ar gael yn fwy hwylus yn Lloegr i ben. Gan mai ychydig o ocsidau manganîs oedd ar gael iddynt, dechreuodd y diwydiant gwydr chwilio ymhellach, mewn rhannau mwy anghysbell o Ynysoedd Prydain, yn cynnwys rhannau o ogledd Cymru.

Erbyn yr 1840au roedd ocsidau manganîs duon wedi’u canfod, a’u cloddio, yn y Bermo ac ardal yr Arennig yn Sir Feirionnydd, ac yn y Rhiw a Chlynnog Fawr yn Sir Gaernarfon. Roedd y dyddodion hyn i gyd yn fychan ac yn gymharol anghynhyrchiol, ond am resymau hollol wahanol.

Yn achos y Bermo a’r Rhiw, buan iawn yr oedd yr ocsidau manganîs duon, meddal, cyfoethog ar wyneb y tir yn troi’n graig galed, debyg i fflint, ddim ond ychydig ddegau o fetrau o dan yr wyneb. Yn y ddau leoliad, nid oedd y bobl yn gwybod am unrhyw ddiben i'r graig galed isod a rhoddwyd y gorau i gloddio, ond nid dyma oedd diwedd y stori.

Daw’r cofnod cynharaf o gloddio am fanganîs yn ardal yr Arennig o 1823 pan dalwyd breindaliadau am fanganîs o “Llanecil mines” (ym mhlwyf Llanycil y mae’r Arennig). Bu cloddio achlysurol mewn nifer o fwyngloddiau a chloddiadau prawf yn yr ardal tan ddechrau’r 20fed ganrif. Mae’r ocsidau manganîs duon hyn i’w cael mewn holltau cul, serth neu wythiennau, sy'n torri trwy greigiau folcanig hynafol o'r oes Ordofigaidd – a elwir yn 'twffau llif lludw'. Er mwyn cyrraedd y gwythiennau cul, serth hyn mae angen cloddio twnelau a suddo siafftiau, ac mae hynny’n fater costus. Buddsoddwyd cryn dipyn o arian yn rhai o’r mwyngloddiau ond y broblem fawr oedd bod angen cludo’r manganîs yn bell i’r gwaith gwydr yn St Helens, ger Lerpwl, ac i rannau eraill o Loegr.

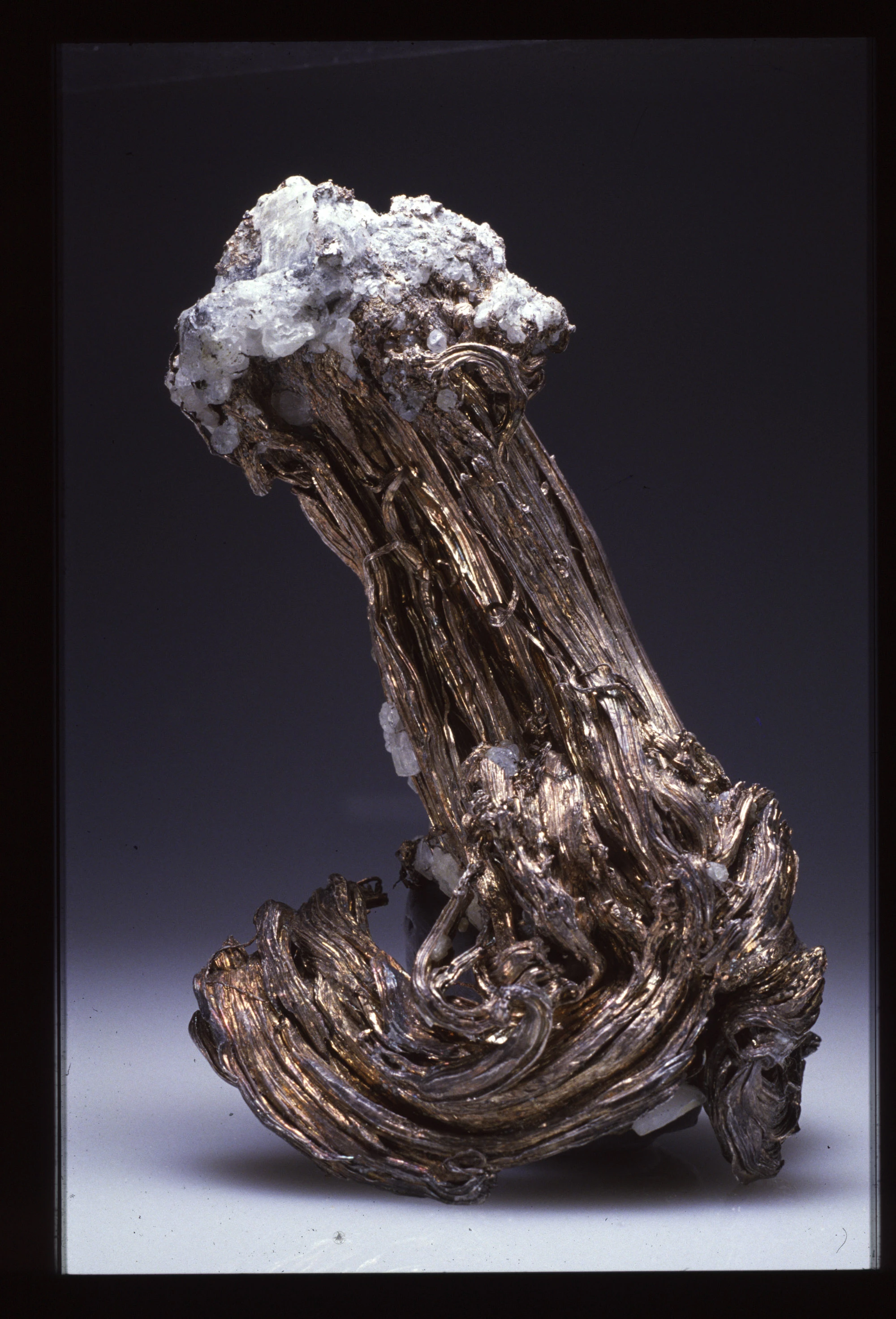

Dim ond ychydig gannoedd o dunelli o’r mwyn a werthwyd i gyd ond roedd bob amser yn cael ei gyfrif yn fwyn o ansawdd da – yn cynnwys dros 70% o fanganîs ocsid. O safbwynt mwynoleg, disgrifiwyd y mwyn fel ‘psilomelan’ – term a ddefnyddir am unrhyw fanganîs ocsid caled, anhysbys, sy’n debyg i swp o rawnwin. Dangosodd astudiaethau dadansoddol modern ei fod yn cynnwys, yn bennaf, sawl haen o cryptomelan a holandit (ocsid manganîs potasiwm ac ocsid manganîs bariwm yn y drefn honno.)

Yn 1827 cafodd manganîs ei ddarganfod yn y Rhiw am y tro cyntaf. Cafodd ei brofi a gwelwyd ei fod yn addas i wneud halen cannu. Anfonwyd samplau at gwmnïau yn Lloegr, yr Alban, Iwerddon, yr Almaen a Rwsia ac, yn yr 1850au, roedd llwythi’n cael eu hanfon ar longau i Lerpwl a Runcorn.

Yn ystod yr 1930au, dywedir bod ocsidau manganîs o'r Bermo wedi’u hanfon i Glasgow i gannu gwydr, ond ychydig iawn o ddyddodion oedd ar gael a daethant i ben o fewn degawd.

Fel sy’n digwydd mor aml, mae datblygiadau gwyddonol yn creu cyfleoedd newydd ac yn canfod diben i ddeunyddiau a oedd gynt yn ddiwerth. Dyna’n union a ddigwyddodd gyda’r creigiau caled, tebyg i fflint, a ganfuwyd o dan yr haen arwynebol o ocsidau manganîs duon ger y Bermo ac yn y Rhiw. Yn y Bermo, gwelwyd bod y graig galed wedi’i gwneud o haenau o graig waddodol a ffurfiwyd ar wely môr dwfn yn y cyfnod Cambriaidd tua 520 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl. Mae 28% ohoni yn fanganîs, ond mae ar ffurf silicadau a charbonadau sy'n ddiwerth ar gyfer gwneud gwydr. Fodd bynnag, tua dechrau’r 1880au, sylweddolwyd bod y graig galed hon oedd yn cynnwys manganîs yn beth delfrydol i’w roi mewn ffwrneisi chwyth i gynhyrchu dur manganîs cryf iawn.

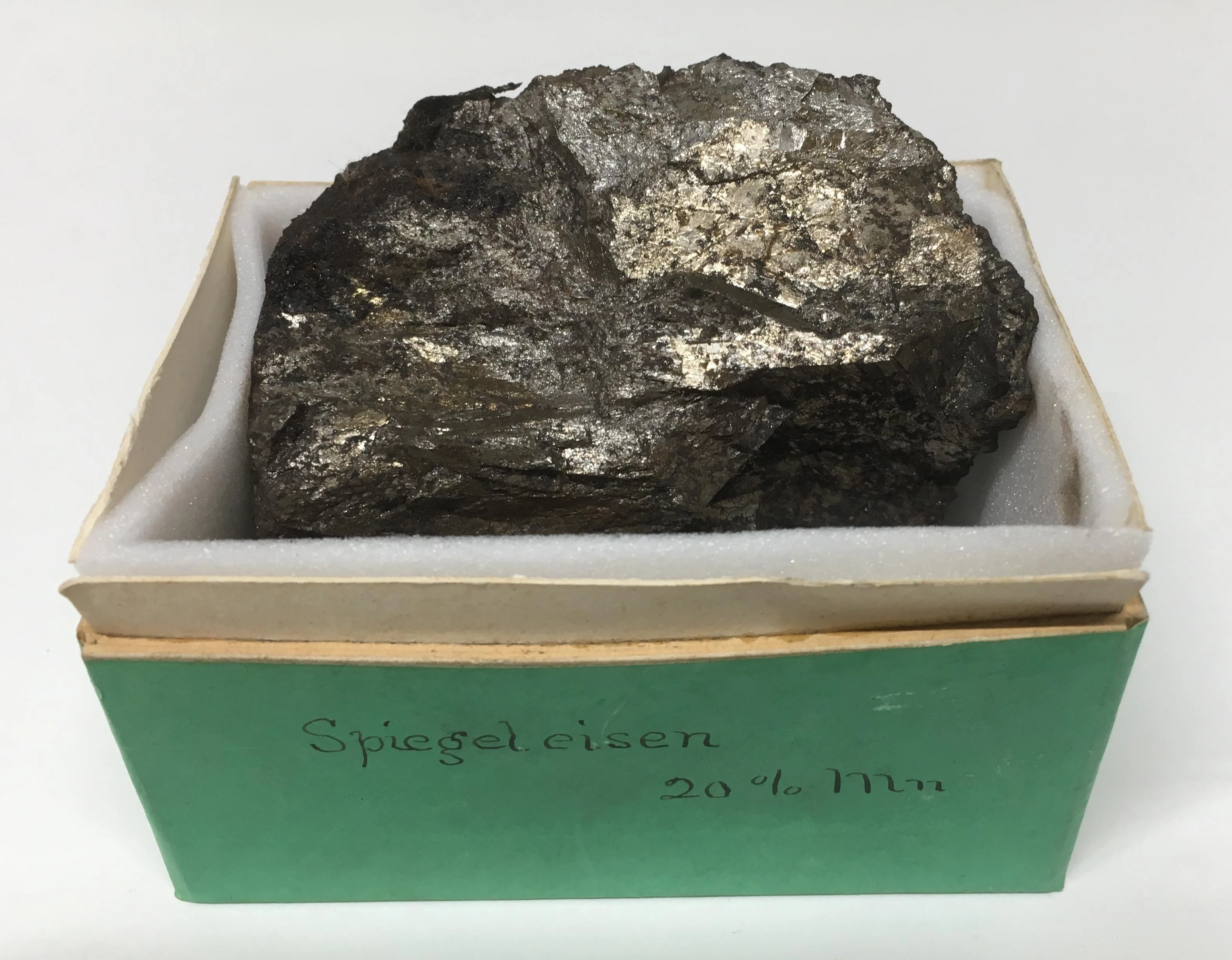

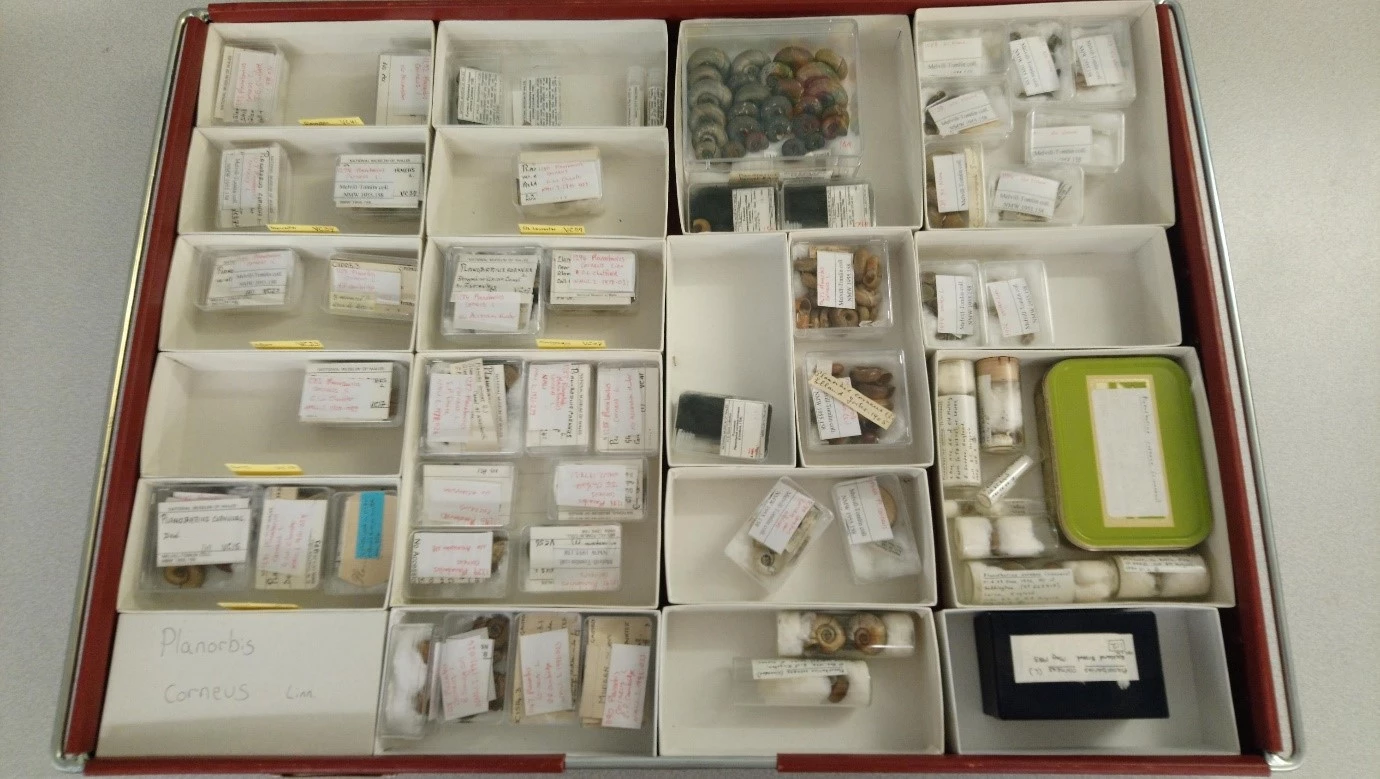

Roedd un o gamau’r broses hon yn cynnwys creu aloion o haearn a manganîs o gyfrannedd benodol. Mae gan yr Amgueddfa enghreifftiau o ‘raddau’ gwahanol yr aloion haearn a manganîs o gasgliad bychan William Terrill (1845-1901) a oedd yn brofwr metel cemegol yn Abertawe.

Agorwyd nifer o fwyngloddiau mewn cyfnod byr ar draws y Rhinogydd, i mewn tua’r wlad o’r Bermo a Harlech, gan gloddio mewn gwely o graig 12 modfedd o drwch yn cynnwys llawer o fanganîs. Erbyn hydref 1886, roedd pedwar mwynglawdd yn cynhyrchu cyfanswm o 400 tunnell o fwyn bob wythnos ac, erbyn 1891, roedd 21 o fwyngloddiau’n gweithio. Oherwydd pwysigrwydd y diwydiant, gosodwyd rhwydwaith eang o draciau dros beth o dir garwaf Cymru. Datblygwyd dulliau anarferol o gloddio’r gwely mwyn tanddaearol a oedd yn aml ar oleddf bas, mewn ‘ystafelloedd’ mawr, gan adael colofnau o’r mwyn yn eu lle i gynnal y to. Roedd darnau o graig gwastraff yn cael eu pentyrru’n daclus ar y llethrau y tu allan i’r mwyngloddiau mewn ffordd na welwyd yn unman arall ym Mhrydain.

Fodd bynnag, nid oedd y mwyn cystal â mwyn o dramor. Felly, dechreuwyd cau’r mwyngloddiau, gyda’r olaf yn cau yn 1928. Cynhyrchwyd cyfanswm o 101,000 tunnell o fwyn o’r mwyngloddiau hyn. Roedd yr ocsidau manganîs duon a gloddiwyd gyntaf yn y Bermo yn rhan o gramen fain a ffurfiwyd trwy ocsidiad yn yr 11,000 o flynyddoedd ers diwedd yr oes iâ ddiwethaf trwy addasu’r carbonadau manganîs mewn cyswllt â dŵr glaw ac aer.