Mae llai nag wythnos tan ddiwrnod Nadolig ac i'r rhan fwyaf ohonom mae'r gwaith paratoi ac addurno yn dod i ben. Mae ein cartrefi yn edrych yn fendigedig, a'r goeden Nadolig yn disgleirio gyda goleuadau. Mae'r cardiau Nadolig wedi eu postio, y negeseuon cyfryngau cymdeithasol wedi eu danfon, a'r anrhegion wedi eu lapio. Mae'r twrci wedi'i archebu a'r pwdin Nadolig wedi ei brynnu (neu ei goginio!). Erys y traddodiadau yma yn rhan bwysig o'r Nadolig yn 2017 ond paham ac o ble y ddaeth y traddodiadau hyn?

Addurniadau

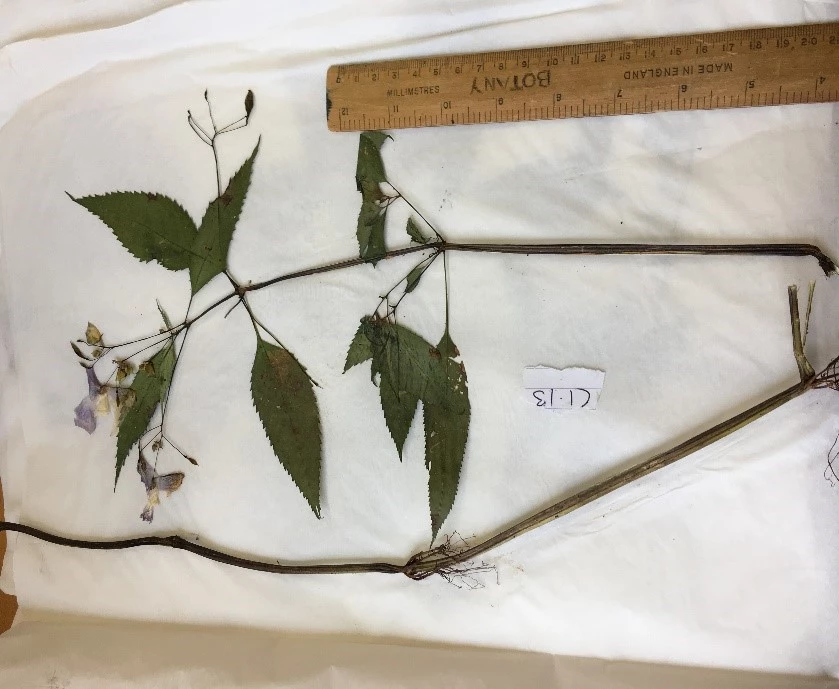

Rydym wedi addurno ein cartrefi ar yr adeg hon o'r flwyddyn ers amser y Paganiaid. Defnyddiwyd bytholwyrdd gan y Paganiaid i gydnabod byrddydd y gaeaf ac i'w hatgoffa bod y Gwanwyn ar ei ffordd. Y Pab Julius 1 benderfynodd taw y 25ain o Rhafgyr fyddai dyddiad dathlu geni Crist, a gan bod y dyddiad hwn yn cwympo yng nghanol dathliadau'r Paganiaid, amsugnwyd rhai o draddodiadau y Paganiaid i mewn i galendr y Cristnogion, gan gynnwys addurno gyda bytholwyrdd, yn enwedig gyda chelyn.

I Gristnogion roedd planhigion bytholwyrdd yn arwyddocâd o fywyd tragwyddol Duw; y celyn yn symbol o goron ddraen yr Iesu ar y Groes, a'r aeron ei yn cynrychioli ei waed. Yn ogystal â hyn, roedd i blanhigion bytholwyrdd eraill arwyddocâd yn ystod y cyfnod. Mae iorwg, er enghraifft, yn blanhigyn sydd yn glynnu, ac felly roedd yn symbol o ddyn yn dal ei afael yn dynn ar Dduw. Ystyrid bod gan rhosmari gysylltiad â'r Forwyn Fair tra bod gan llawryf, neu glust yr Asen, gysylltiad â llwyddiant, yn enwedig llwyddiant Duw yn goroesi yn erbyn y Diafol. Credid bod celyn a iorwg yn blanhigion benywaidd a gwrywaidd. Celyn a'i bigau miniog yn cynrychioli'r dyn tra bod yr Iorwg yn cynrychioli'r fenyw. Pa bynnag un o'r rhain a fyddai'n croesi'r trothwy gyntaf fyddai'n dynodi pen y cartref am y flwyddyn i ddod. Anlwc oedd addurno gyda'r bytholwyrdd cyn Noswyl Nadolig ac anlwc hefyd oedd ei dynnu o'r cartref cyn y ddeuddegfed nos.

Yng nghefn gwlad Cymru addurnwyd cartrefi gyda phlanhigion bytholwyrdd yn oriau man y bore cyn mynd i'r gwasanaeth Plygain yn yr eglwys blwyfol. Gwasanaeth garolau oedd gwasanaeth y Plygain a oedd yn cael ei gynnal fel arfer rhwng 3 o'r gloch a 6 o'r gloch y bore. Unigolion a grwpiau fyddai'n canu'r carolau. Arferid goleuo'r ffordd i'r egwlys gyda chanhwyllau'r Plygain ac fe'i gosodwyd hefyd yn yr egwlys i'w addurno a'i oleuo. Defnyddiwyd canhwyllau fel addurn gan y Paganiaid i'w hatgoffa am olau'r haul ac fe'u defnyddiwyd gan Gristnogion fel atgoffeb am bresenoldeb Duw. Cyn ddyfodiad trydan goleuwyd coed Nadolig gyda chanwyllau.

Cliciwch yma i glywed Parti Fronheulog ac eraill yn canu’r garol “Addewid rasusol Ein Duw”. Recordiwyd gan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru yn ficerdy Llanrhaeadr-ym mochnant wedi’r Swper Plygain yno ym mis Ionawr 1966.

https://www.casgliadywerin.cymru/items/738256

Coed Nadolig ac Addurniadau Eraill

Mae tystiolaeth ar gael i awgrymu bod coed Nadolig wedi cael eu defnyddio fel addurn Nadolig ym Mhrydain mor bell yn ôl â'r 1790au, a bod y siap triongl i Gristnogion yn arwydd o'r cysylltiad rhwng y mab, y tad a'r ysbryd glân. Ddaeth y traddodiad yn fwy poblogaidd yn oes Fictoria oherwydd i'r Frenhines Fictoria a'r Tywysog Albert ddefnyddio coeden Nadolig i addurno Castell Windsor yn 1841 ac eto yn 1848. Ymddangosodd llun o'r teulu gyda'r goeden wedi ei haddurno yn The London Illustrated News.

Yn yr 1920au dechreuodd addurniadau artiffisial gymryd lle'r planhigion bytholwyrdd, yn enwedig mewn trefi a dinasoedd. Roedd addurniadau artiffisial erbyn hyn yn rhatach i'w prynnu, ac wedi cael eu gwerthu mewn siopau fel Woolworths ers yr 1880au, yn ogystal â losin, cacennau a rhubannau. Yn y 1920au a'r 1930au gwelwyd dechrau ar yr arfer o lapio anrhegion. Gwelwyd y goleuadau trydanol cyntaf ar goeden Nadolig yn Efrog Newydd yn 1882, dim on tair mlynedd ar ol ddyfeisio'r bwlb golau.

Adeg yr ail Rhyfel Byd daeth cadwynni papur yn boblogaidd fel addurniadau Nadolig gan ei bod yn hawdd i'w creu yn y cartref, ac yn y 1950au gwelwyd coed Nadolig artiffisial yn cael eu gwerthu.

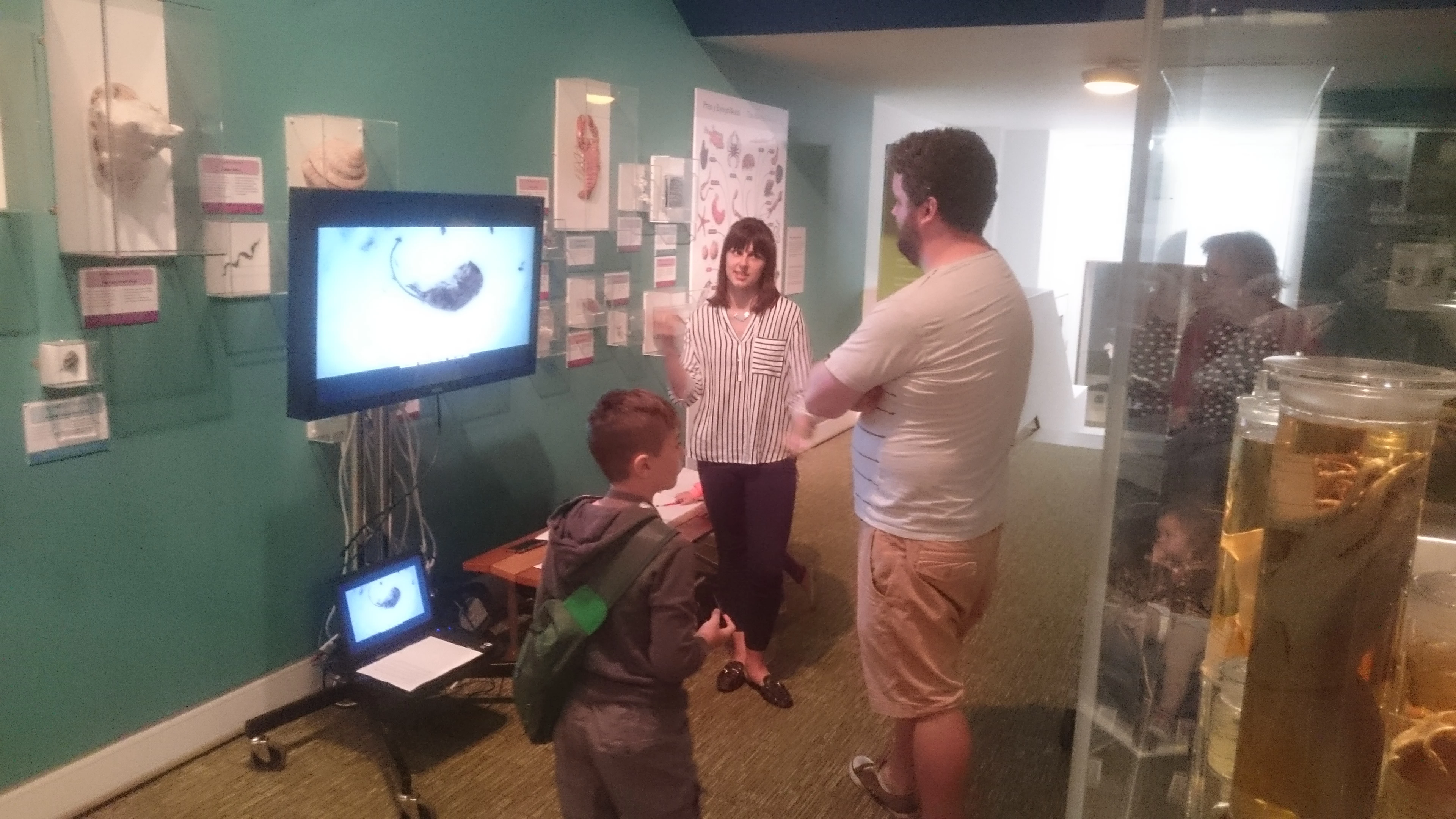

Pob adeg Nadolig yn Amgueddfa Werin Cymru mae'r staff yn addurno'r adeiladau gydag addurniadau sy'n addas ar gyfer y cyfnod a'r ardal.

Cardiau Nadolig

Yn 1840 dyfeisiwyd y "Penny Post" gan Rowland Hill ac yn sgil hynny cynhyrchwyd 1000 o gardiau Nadolig gan Sir Henry Cole yn ei siop gelf yn Llundain er mwyn eu gwerthu am swllt yr un. Erbyn 1870, gan bod y system trenau erbyn hyn yn fwy cyflym, roedd pobl yn gallu danfon eu cardiau Nadolig am hanner ceiniog. Yng nghasgliad Amgueddfa Victoria ac Albert yn Llundain, mae carden Nadolig a ddanfonwyd o Gwrt-yr-Ala yng Nghaerdydd yn 1844.

Bwydydd Nadolig

Erbyn heddiw cysylltir y Nadolig â bwyta bwyd moethus fel pwdin Nadolig. Yn draddodiadol gwnaethpwyd y pwdin Nadolig 5 wythnos cyn y Nadolig ac yn Nghymru arferid rhoi tro i bob aelod o'r teulu, yn cynnwys y plant a'r gweision, i droi y gymysgedd, gyda phen y teulu yn cael y fraint o droi y gymysgedd yn gyntaf. Yn y gymysgedd rhoddwyd eitemau a oedd yn rhagweld y dyfodol. Os daethpwyd o hyd i fodrwy priodas, byddai hyn yn darogan priodi yn y dyfodol. Os byddai dyn ifanc yn dod o hyd i fotwm yn y gymysgedd, byddai hyn yn darogan dyfodol unig fel hen lanc. Os byddai merch ifanc yn dod o hyd i winiadur byddai hyn yn darogan dyfodol heb briodas a bywyd unig fel hen ferch. Os dod o hyd i chwe ceiniog, byddai lwc dda yn dod i'ch rhan.

Bwyd traddodiadol arall a welid adeg y Nadolig yng Nghymru oedd cyflaith. Math o losin oedd hwn wedi ei wneud o fenyn, triog a siwgr wedi eu ferwi. Y gamp oedd tynnu a rolio'r gymysgedd tra ei fod yn oeri ac yna ei dorri wrth iddo galedu yn ddarnau bach. Roedd y rysait yn gallu amrywio o ardal i ardal. Cliciwch yma i weld ffilm o gyflaith yn cael ei baratoi

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=26bDQqRQICY

Nadolig Llawen i chi gyd!