Mis Hanes LHDT+ 2022

, 1 Chwefror 2022

Mae Chwefror bob blwyddyn yn Fis Hanes LHDT+, gyda digwyddiadau gydol y mis yn helpu i hyrwyddo hanes a phrofiad bwyd pobl LHDT+. Fel arfer, mae thema wahanol ar gyfer y mis, a'r thema eleni yw ‘Gwleidyddiaeth mewn Celf’.

Mae Amgueddfa Cymru wedi trefnu nifer o ddigwyddiadau ar gyfer Mis Hanes LHDT+ 2022:

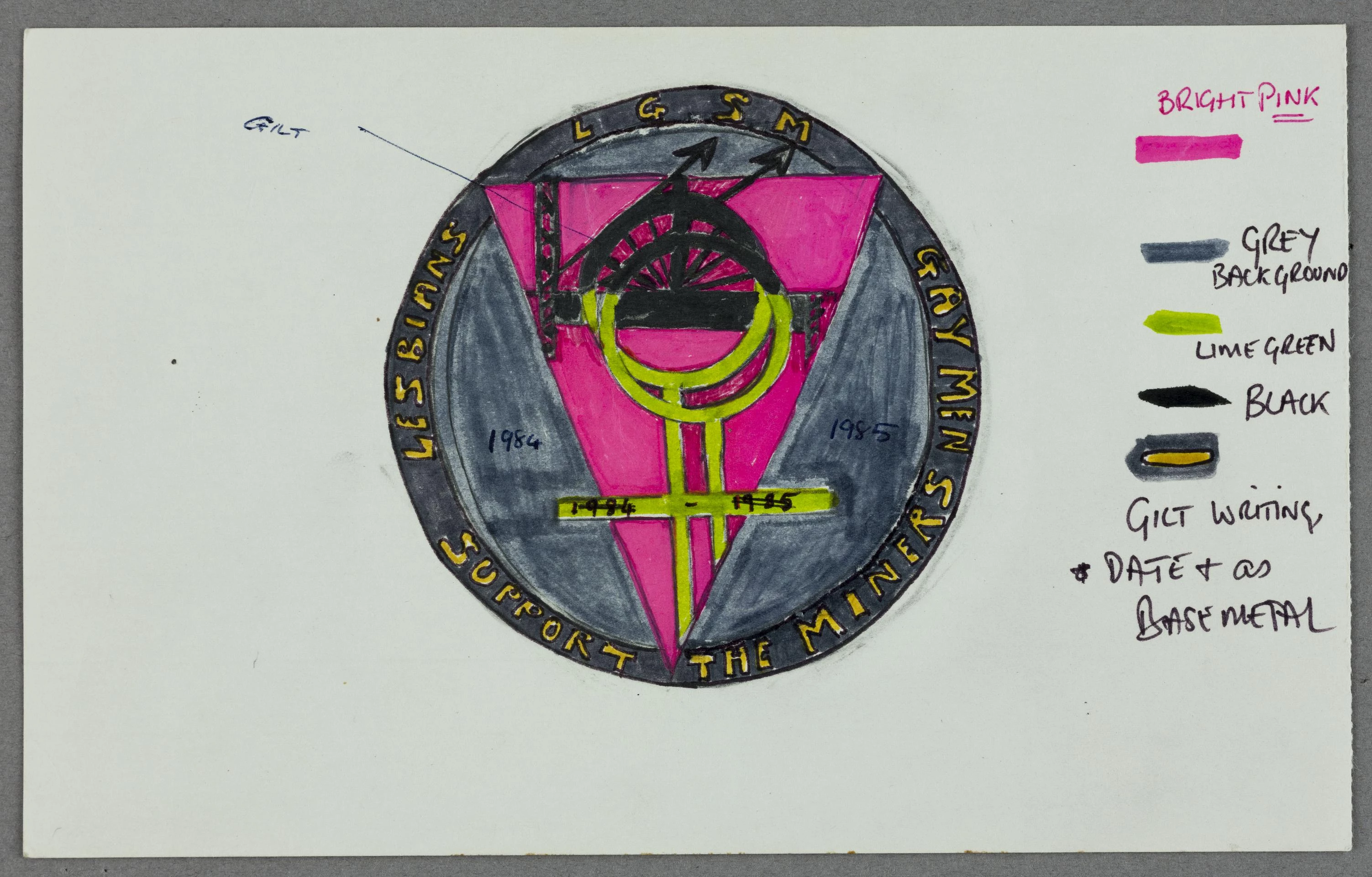

Drwy gydol y mis bydd cynllun gwreiddiol bathodyn Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners Jonathan Blake o 1985 i'w weld yn Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru. Bydd yn cael ei arddangos yn oriel Cymru... yn Sain Ffagan ar y cyd â bathodyn gwreiddiol LGSM. Grŵp oedd Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners fu'n codi arian ar gyfer glowyr de Cymru oedd yn dioddef yn ystod streic fawr 1984-85. Erbyn diwedd 1984 roedd unarddeg o ganghennau LGSM ar draws y DU. Roedd pob cangen wedi 'gefeillio' â chymuned benodol, a changen Llundain yn cefnogi cymunedau yng nghymoedd Nedd, Dulais a Tawe Uchaf. Anfarwolwyd yr hanes hwn, ac ymweliad LGSM ag Onllwyn, yn 2014 yn y ffilm Pride. Mark Ashton, un o sylfaenwyr LGSM ym 1984, oedd un o wynebau Mis Hanes LHDT+ 2021 ac mae'n fraint dathlu eto eleni lwyddiannau rhyfeddol ymgyrch Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners.

Fel rhan o gyfres 'Sgyrsiau Amgueddfa' Amgueddfa Cymru bydd y curadur Mark Etheridge yn cynnal sgwrs ar gasgliad LHDT+ Sain Ffagan a phwysigrwydd cynrychiolaeth mewn casgliadau. Gallwch archebu tocyn ar - Sgyrsiau'r Amgueddfa: Casgliad LHDTQ+ Sain Ffagan | English | Amgueddfa Cymru.

Rydyn ni hefyd yn datblygu project cyffrous ar gyfer Mis Hanes LHDT+. Diolch i nawdd Cyngor y Celfyddydau, bydd LGBTQ+ History Wales Songbook gan Gareth Churchill yn cael ei berfformio yn Sefydliad y Gweithwyr Oakdale yn Sain Ffagan yn ystod y mis. Bydd y perfformiad cerddorol i lais a phiano/allweddell yn dathlu a rhoi llais cerddorol i gasgliad hanes LHDTQ+ Sain Ffagan. Perfformiad caeëdig fydd hwn i ddechrau, yn cael ei ffilmio a'i ddarlledu ar-lein fel diweddglo i Fis Hanes LHDT+ a'i hysbysebu ar bob un o sianeli cyfryngau cymdeithasol yr Amgueddfa.

Wrth gwrs, nid am un mis yn unig y dylai hanes LHDTQ+ gael ei ddathlu. Cadwch lygad drwy gydol 2022 am ragor o arddangosiadau a digwyddiadau yn safleoedd Amgueddfa Cymru. Dyma rai o'r cynlluniau sydd ar y gweill:

Yn Sain Ffagan mae nifer o wrthrychau LHDTQ+ bellach yn cael eu harddangos yn orielau Cymru... a Byw a Bod... Yn ogystal â'r bathodynau LGSM, mae tebot a phadl yn perthyn i Fenywod Llangollen (o bosib y pâr lesbiaidd enwocaf erioed) a chopi o gerddoriaeth We'll Gather Lilacs a gyfansoddwyd gan Ivor Novello.

O ganol mis Mawrth bydd gwrthrychau o'r casgliad LHDTQ+ i'w gweld yn Amgueddfa Genedlaethol y Glannau fel rhan o arddangosfa Trawsnewid. Project gan Amgueddfa Cymru ar gyfer pobl ifanc LHDTQ+ rhwng 16-25 oed yw Trawsnewid. Mae'n edrych ar ffigurau queer, neu sydd ddim yn glynnu at rywedd ddeuaidd yn hanes Cymru ac yn cefnogi cyfranogwyr i greu gwaith wedi ei ysbrydoli gan brofiad bywyd.