Menywod Llangollen: Stori ar Blât

, 25 Awst 2017

Fel arfer Mis Hanes LGBT ym mis Chwefror yn frith o erthyglau a digwyddiadau yn ymwneud â chyfeiriadedd rhywiol, hunaniaeth, a’u hanes. Ond ddylai hanes byth gael ei gyfyngu i un mis, felly ar achlysur Pride Cymru yng Nghaerdydd, dyma gyfle da i ystyried hanes LGBT.

Stori ar Blât

Ystyriwch, er enghraifft, y plât yn nghasgliad Amgueddfa Cymru ag arno olygfa o ddwy fenyw yn marchogaeth. Mae’n un o filoedd o eitemau crochenwaith printio troslun glas a gwyn fu mor boblogaidd ers y 19eg ganrif. Ond mae’r llun hwn yn fwy nag addurn.

Plât, Crochendy Morgannwg, oddeutu 1813-1839

“Menywod Llangollen” yw teitl y gwaith, a ysbrydolwyd gan hanes dwy fenyw – y Fonesig Eleanor Butler a Miss Sarah Ponsonby.

Taniwyd fflam rhwng Eleanor a Sarah gartref yn Iwerddon, a chan ofni’r atyniad hwn rhwng dwy ferch, ceisiodd y ddau deulu eu gwahardd rhag gweld ei gilydd. Yn benderfynol o fod gyda’i gilydd, dihangodd y ddwy liw nos, ond cawsant eu dal ymhen fawr o dro. Brwydrodd Eleanor a Sarah yn ddiflino am yr hawl i fod gyda’i gilydd tan i’w teuluoedd ildio, a gadel iddynt fynd.

Teithiodd y ddwy i Gymru ac ymgartrefu ger Llangollen, gan fyw yno am dros 50 mlynedd.

Enwogrwydd 'Menywod Llangollen'

Lledodd yr hanes amdanynt yn gyflym, a byddent yn llythyra gydag enwogion megis Shelley, Byron, Syr Walter Scott, Dug Wellington, Josiah Wedgewood a Caroline Lamb, gyda nifer yn ymweld â’r ddwy yn Llangollen. Parhaodd y diddordeb yn y cwpl wedi eu marw ym 1829 a 1831 ac erbyn heddiw maent yn adnabyddus fel un o’r cyplau lesbiaidd enwocaf erioed.

Roedd y ddwy yn bendant yn ystod eu bywydau nad oedden nhw am gael llun neu bortread wedi’i dynnu.

Roedd y ddwy yn bendant yn ystod eu bywydau nad oedden nhw am gael llun neu bortread wedi’i dynnu.

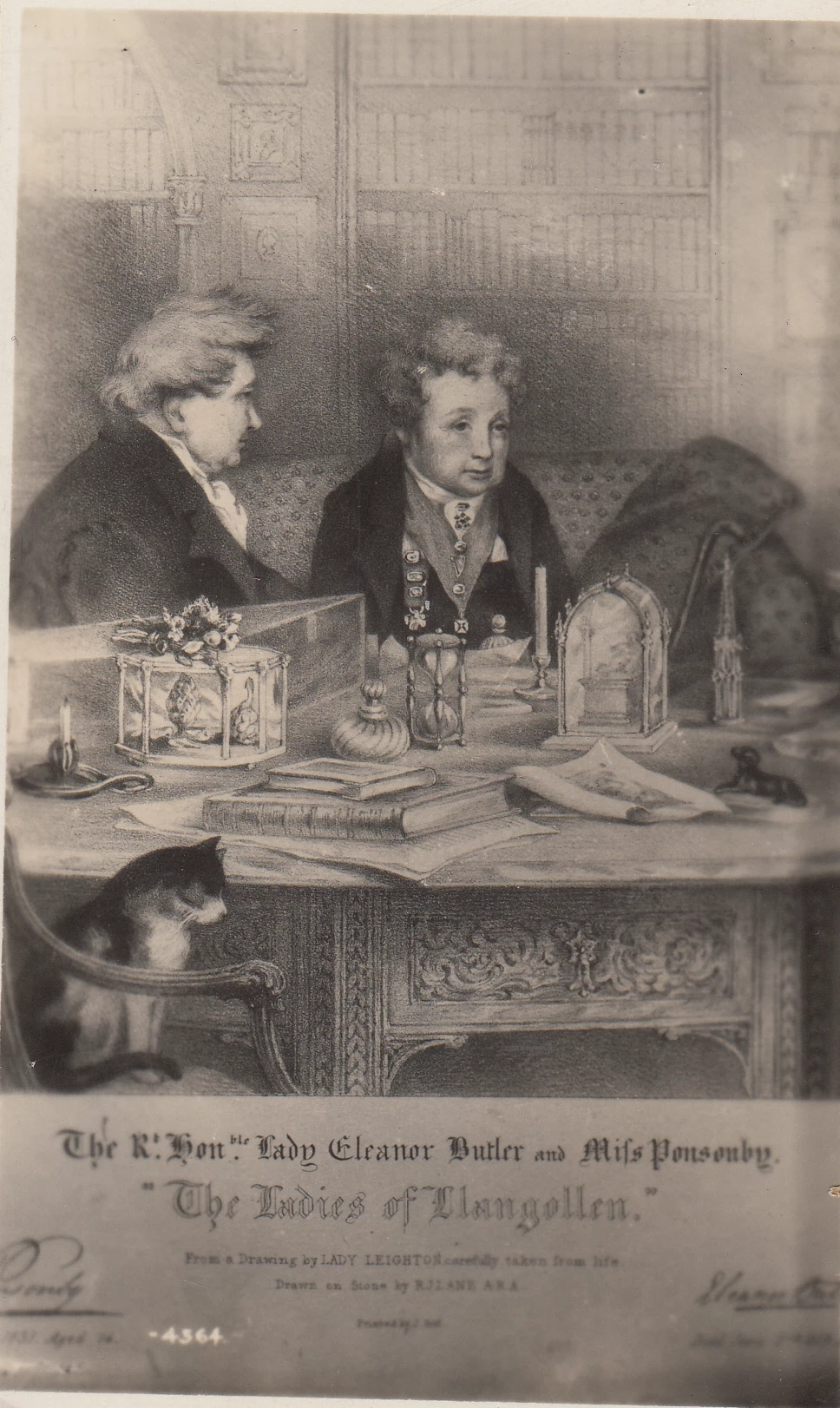

Ond pan ymwelodd y Fonesig Parker ym 1829, perswadiodd ei mam i ddwyn sylw Eleanor a Sarah tra’i bod hithau’n creu brasluniau cyflym o dan y bwrdd. Erbyn hynny roedd Eleanor yn hollol ddall, felly llwyddodd y Fonesig Parker i fraslunio’i hwyneb yn llawn, tra bod Sarah mewn proffil. Wedi i’r cwpwl farw, datblygodd y brasluniau yn ddarlun llawn o’r ddwy yn eu llyfrgell a gwerthu copïau i godi arian at elusennau.

Portread o'r Foneddiges Eleanor Butler a Sarah Ponsonby, wedi'i ddarlunio ar sail sgets cyfrin a wnaethpwyd yn eu cartref yn Llangollen

Dwyn Portread

Oddeutu 1830 copïwyd y darlun heb ganiatâd gan James Henry Lynch ac ef gynhyrchodd y darlun mwyaf adnabyddus o Eleanor a Sarah. Masgynhyrchwyd y darlun a’i ddefnyddio ar amryw o nwyddau megis cofroddion twristiaid, cardiau post a chloriau nifer o lyfrau.

Portread 'Lynch' o'r Foneddiges Eleanor Butler a Sarah Ponsoby, wedi'i gopïo yn helaeth o'r portread 'Llyfrgell'. Fe werthwyd nifer sylweddol o'r print hwn.

Mae darlun Lynch yn eu dangos yn sefyll yn yr awyr agored ac yn gwisgo’r clogynnau marchogaeth oedd yn gymaint o ffefryn gan y dwy. Ymddangosodd y gwaith tua diwedd y cyfnod o ddiddordeb cyhoeddus ym mywyd Eleanor a Sarah; erbyn troad y 19eg ganrif roedd hanes y menywod wedi lledu a nifer yn cyhoeddi eu stori.

Ysgrifennodd William Wordsworth gerdd ym 1824 ar ôl ymweld â’r ddwy. Ymddangosodd y crochenwaith felly mewn cyfnod pan oedd diddordeb mawr yn eu hanes.

Crochenwaith Morgannwg a Hanes 'Plât Llangollen'

Mae’r plât cyntaf yn dangos y ddwy ar eu ceffylau yn siarad â gwr yn cario pladur dros ei ysgwydd. Yn y cefndir mae gyrr o wartheg, tref Llangollen, afon Dyfrdwy a fersiwn hynod ramantus o gastell Dinas Brân.

Mae’r plât cyntaf yn dangos y ddwy ar eu ceffylau yn siarad â gwr yn cario pladur dros ei ysgwydd. Yn y cefndir mae gyrr o wartheg, tref Llangollen, afon Dyfrdwy a fersiwn hynod ramantus o gastell Dinas Brân.

Gwyddom ddyddiad cynhyrchu cynharaf y plât o stamp y gwneuthurwr ar y gwaelod – ‘BB&I’, sef Baker, Bevin and Irwin o Grochendy Morgannwg ac a ddefnyddiwyd oddeutu 1815-25. Daeth yn un o blatiau enwocaf y crochendy hwnnw. Er bod Eleanor a Sarah yn frwd dros gadw dyddiaduron, ac i’r gwaith gael ei gynhyrchu yn ystod bywydau’r ddwy, nid oes sôn amdano yn eu hysgrifau. Wyddon ni ddim os oeddent yn gwybod am fodolaeth y platiau neu wedi cytuno i gael eu portreadu yn y fath fodd.

Ym 1838 daeth Crochendy Morgannwg dan reolaeth y gwr busnes o Abertawe Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn ac fe barhaodd i gynhyrchu’r platiau dan stampiau Morgannwg, Abertawe a Cambrian tan oddeutu 1840. Mae’n debygol ei fod yn defnyddio’r un dyluniad yng Nghrochendy Cambrian ym 1925; roedd cystadleuaeth gref rhwng y ddau grochendy a byddent yn aml yn copïo gwaith ei gilydd.[1]

Y cyswllt rhyfeddol yma yw taw un o aelodau enwocaf teulu Lewis oedd Amy Dillwyn. Menyw fusnes oedd Amy, ac yn ogystal a bod yn nofelydd blaenllaw, hi gymerodd yr awenau yng ngweithfeydd sinc ei thad wedi iddo farw.

Roedd Amy hefyd mewn perthynas hoyw. Braf yw breuddwydio bod Amy, wedi gweld plât Crochendy Morgannwg, wedi dwyn perswâd ar ei thad i’w gynhyrchu yng Nghrochendy Cambrian, ond nid oes unrhyw dystiolaeth o hyn.

Manylun o blât glas yn dangos darlun o Sarah Ponsonby ac Eleanor Butler

© Norena Shopland

Manylun o blât glas yn dangos darlun o Sarah Ponsonby ac Eleanor Butler

© Norena Shopland

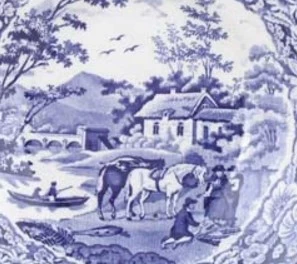

Mae’n anodd dweud os taw plât Crochendy Morgannwg oedd y cyntaf i gael ei gynhyrchu, neu plât gan William Adams o Stoke. Ladies of Llangollen yw enw’r dyluniad hwn hefyd, gyda dwy fenyw mewn clogynnau marchogaeth yn sefyll dros ŵr sydd yn dangos pysgodyn mawr i’r ddwy. Yn y cefndir mae’r ceffylau, ac yn y pellter mae dau ŵr mewn cwch ar afon gyda phont drosti a bwthyn gwerinol ar y lan. Ar y gorwel mae mynydd Cadair Bedwyr.

Mae’n anodd dweud os taw plât Crochendy Morgannwg oedd y cyntaf i gael ei gynhyrchu, neu plât gan William Adams o Stoke. Ladies of Llangollen yw enw’r dyluniad hwn hefyd, gyda dwy fenyw mewn clogynnau marchogaeth yn sefyll dros ŵr sydd yn dangos pysgodyn mawr i’r ddwy. Yn y cefndir mae’r ceffylau, ac yn y pellter mae dau ŵr mewn cwch ar afon gyda phont drosti a bwthyn gwerinol ar y lan. Ar y gorwel mae mynydd Cadair Bedwyr.

Cynhyrchodd Adams gyfres grochenwaith dan y teitl ‘Native’ yn y 1820au, ac roedd y plât hwn yn rhan o’r gyfres honno. Yn fuan caffaelwyd y dyluniad gan F. ac R. Pratt o Fenton, Swydd Stafford gan ailenwi’r gyfers yn ‘Pratt’s Native Scenery’ a’i hatgynhyrchu rhwng 1880 a 1920. Prynwyd y busnes gan Cauldon yn y 1920au a cynhyrchwyd yr un dyluniad tan y 1930au.

Mae diddordeb mawr o hyd ym mywydau Eleanor a Sarah, yn enwedig wrth i ni drafod y diffiniad o berthynas lesbiaid yn y gorffennol. Er gwaetha’r diddordeb, prin yw’r sylw a roddir i’r crochenwaith glas a gwyn yma, a peth da yw cofio bod y gweithiau yma yn rhan o gasgliad LGBT Amgueddfa Cymru.

NORENA SHOPLAND

Awdur Forbidden Lives: LGBT stories from Wales a gyhoeddir gan wasg Seren, 17eg o Hydref, 2017

Gwefan: http://www.rainbowdragon.org

[1] Diolch i Andrew Renton, Ceidwad Celf Amgueddfa Cymru am gadarnhau