Ar daith gyda Cranogwen

, 21 Chwefror 2023

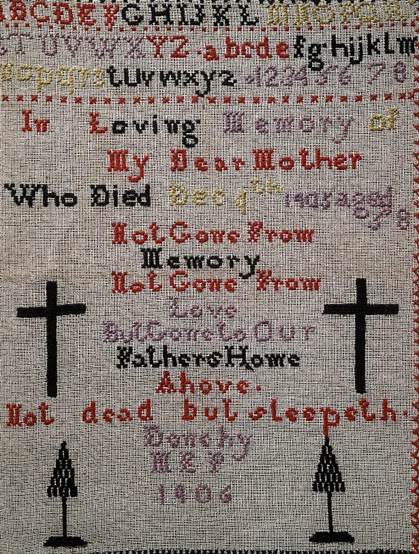

Wrth geisio creu darlun o fywydau pobl, yn enwedig rhai o’r gorffennol, y pethau bach sy’n aml yn dod â nhw'n fyw – broets neu docyn darlith efallai – ac mae dwy eitem yng nghasgliad Amgueddfa Cymru yn sicr yn gwneud hynny.

Mae'r ddwy yn perthyn i Cranogwen – enw barddol Sarah Jane Rees (1839–1916), capten llong, bardd, llenor, golygydd ac ymgyrchydd dirwest wnaeth fyw rhan fwyaf o'i hoes yn nhref fechan Llangrannog, Sir Aberteifi. Yno y cafodd hi’i geni, ac oddi yno fe deithiodd hi drwy gydol ei hoes nes dod erbyn troad yr 20fed ganrif yn un o ferched mwyaf adnabyddus Cymru. Dyma hefyd lle roedd hi’n byw gyda’i phartneriaid – Fanny Rees “Phania” (1853-1874) fu farw yn 21 oed, a Jane Thomas (1850-?) sy’n cael ei disgrfio yn y rhan fwyaf o’i datganiadau cyfrifiad fel ‘gweithiwr domestig’, ‘morwyn’ neu ‘glanhawraig’.

Byddai Cranogwen yn aml oddi cartref, yn cyfrannu at fyrdd o brojectau ac yn darlithio, ond aeth ar ei thaith gyntaf ym 1866. Roedd hyn flwyddyn ar ôl ennill gwobr farddoniaeth yr Eisteddfod – oedd yn ddadleuol pan ddatgelwyd bod menyw wedi curo’r dynion. Felly, pan ddechreuodd ar ei theithiau roedd hi eisoes yn adnabyddus, fel y nododd un o newyddiadurwyr Y Gwladgarwr:

“Fe gofia y darllenydd mai y ferch ieuanc hon a gymerodd y wobr yn Eisteddfod Aberystwyth am y gan i'r Fodrwy Briodasol. Wedi clywed hynny, a deall hefyd bod ein beirdd blaenllaw, megys Islwyn a Ceiriog yn cystadlu, braidd nad oeddwn yn hanner credu fod rhyw 'faw yn y caws' yn rhywle.” [i]

Canolbwynt taith Cranogwen oedd ei darlith Ieuenctyd a Diwylliant eu Meddyliau, ond dyma hi’n ddiweddarach yn cynnwys dwy ddarlith arall, Anhebgorion Cymeriad da ac Elfennau Dedwyddwch – pob un yn trafod gwella cymeriad pobl. Gan ei bod hi'n darlithio yn Gymraeg, cafodd y darlithiau sylw yn y wasg Gymraeg a braidd dim sylw yn y wasg Saesneg.

Dechreuodd Cranogwen ei thaith yn ardal Aberystwyth, felly gobeithio bod Jane wedi gallu mynd gyda hi i gynnig rhywfaint o gefnogaeth. Ond wrth i’w darlithoedd ddod yn fwy poblogaidd roedd Cranogwen yn teithio ymhellach oddi cartref, ac o fewn deufis daeth bron i fil o bobl i wrando arni yng Nghapel Brynhyfryd Abertawe – tipyn o her i unrhyw un felly gobeithio bod Jane yno i i’w chefnogi.

Lledodd y sôn amdani’n gyflym, ac fel y nododd un o newyddiadurwyr Baner ac Amserau Cymru: ‘Nid oes angen yn y byd myned i drafferthu rhoddi canmoliaeth i'r ddarlithyddes hon, o herwydd mae ei henw wedi myned eisoes yn eithaf adnabyddus bron trwy Gymru.[ii]

Roedd yn cael ei chanmol ym mhobman gan wneud i un newyddiadurwr feddwl i ddechrau na fedrai fod cystal ag yr oedd pobl yn ei ddweud: ‘a chan ein bod wedi clywed y fath ganmoliaeth iddi, yr oeddym yn dysgwyl ei bod yn dda. Ond ni ddaeth erioed un ddychymyg i galon neb o honom ei bod mor gampus ag y mae, ac mor feistrolgar ar ei gwaith.’ [iii]

Dro ar ôl tro cafodd adolygiadau gwych a tyfodd ei darlith awr yn ddwy awr a mwy wrth i bwysigion lleol ymddangos ar y llwyfan ochr yn ochr â hi, gan fynnu siarad hefyd. Heidiai beirdd lleol ati, gan ysgrifennu englynion iddi, a llawer o'r rheini'n cael eu cyhoeddi yn y papurau. Roedd merched hefyd yn dilyn ôl ei throed ac yn camu i’r llwyfan.

Roedd hyn yn achosi pryder.

Ddylai merched, yn enwedig ‘merched ifanc’ (roedd hi’n 27 ar y pryd) ddim darlithio, meddai’r dynion oedd yn cwyno bod merched yn siarad yn gyhoeddus ynamhriodol. ‘The inhabitants of South Wales,’ meddai'r Cardiff Times, ‘are running wild with the young ladies who are lecturing about the country [and] in the opinion of many eminent men this is going too far.

At the recent meeting of the Association of the Calvinistic Methodists held at Caernarvon, the Rev. Henry Rees, and eminent minister, whose name is known through the Principality, spoke against female preachers, and stated that it would be far more becoming in those who are fond of preaching to attend to those duties which belong to their sex. We are glad that a gentleman of Mr Rees’s standing has set his face against this new mania.[iv]

‘Ai nid gartref mae lle y merched hyn?’ gofynnodd Seren Cymru 'a ydym yn barod i weled ein heglwysi yn cael eu britho, os nad yn gorlifo â merched yn darlithio.’[v]

Anwybyddodd y rhan fwyaf o newyddiadurwyr y cwyno, a pharhau i ganmol Cranogwen.

Roedd y sgyrsiau fel arfer yn cychwyn am 7pm gyda thocynnau yn 6d (tua £2 heddiw). Roedd y cynulleidfaoedd yn enfawr a nifer yn nodi sut y byddai gwrandawyr yn aml yn eistedd wedi'u cyfareddu am ddwy awr yn nodio mewn cytundeb, cyn rhoi cymeradwyaeth fyddarol iddi. Nodwyd bod elw bron pob un o'i sgyrsiau yn mynd i dalu dyledion capeli.

Parhaodd Cranogwen i deithio drwy gydol 1867 ac mae dyddiad 2 Ionawr ar y tocyn sydd yn Amgueddfa Cymru. Does dim adroddiad papur newydd ar y ddarlith ym Mrynmenyn, Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr, ond gyda cymaint o ddarlithoedd a’r daith erbyn hyn yn flwydd oed, fyddai pob noson ddim yn cael yr sylw.

Ym 1869–1870 aeth Cranogwen ar daith i’r Unol Daleithiau gan draddodi'r un math o ddarlithoedd – byddai angen i ni archwilio’r cofnodion mewnfudo i weld a aeth Jane gyda hi.

Parhaodd Cranogwen â’i gwaith da ar ôl dychwelyd i Gymru, ac ar ddechrau’r ugeinfed ganrif dechreuodd ymwneud â'r mudiad dirwest, fel llawer o wragedd amlwg eraill. Roedd meddwdod, yn enwedig ymhlith merched, yn endemig wrth iddyn nhw geisio dianc rhag eu bywydau caled, a sefydlwyd nifer o undebau i geisio mynd i’r afael â hyn gan gynnwys Undeb Merched y Rhondda, a sefydlwyd ym mis Ebrill 1901. Roedd y mudiad mor llwyddiannus fe benderfynwyd ei ehangu, a Cranogwen, fel yr Ysgrifenyddes Defnyddol gyda’i chyfeiriad yn Llangrannog, yn allweddol yn newid yr enw i Undeb Dirwestol Merched y De (UDMD). Unwaith eto, roedd Cranogwen yn teithio'n helaeth gyda'r Undeb.

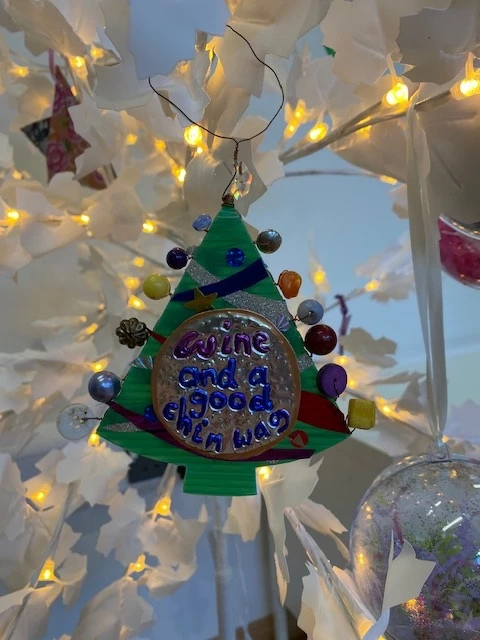

Wrth gyrraedd pob tref byddai aelodau’r Undeb yn gorymdeithio drwy’r strydoedd gan gario baneri, cyn aros mewn capel i weddïo, canu emynau a darllen o'r Beibl cyn gwrando ar areithiau gan aelodau blaenllaw. Byddai siaradwyr gwadd hefyd gan gynnwys menywod adnabyddus o Gymru fyddai’n denu'r cynulleidfaoedd yn eu cannoedd. Ar ôl y digwyddiad byddai te a theisen a chyfle i gymdeithasu, arian yn cael ei gasglu, a byddai pamffledi a bathodynnau ar gael i'w prynu. Yn dechnegol, broets yw’r enghraifft yng nghasgliad Amgueddfa Cymru, ac nid yw’n glir ai’r broetsys hyn oedd y bathodynnau fyddai Cranogwen yn eu gwerthu.

Erbyn Rhagfyr 1901, roedd canghennau newydd o UDMD yn ymddangos ledled de Cymru ac erbyn i Cranogwen farw ym 1916 roedd 140 o ganghennau ar draws y De.

Roedd Cranogwen yn ddiflino, ac allwn ni ond rhyfeddu at ei hegni. Yn ogystal â’i holl weithredoedd da, roedd hi’n esiampl i gymaint o ferched ifanc i fod yn llenorion ac areithwyr, dim ots beth ddwedai’r dynion.

Bu farw Cranogwen yn 1916 yn nhŷ ei nith yn Wood Street Cilfynydd, Rhondda Cynon Taf. ‘No other woman enjoyed popularity in so many public spheres'[vi] nododd y Cambrian Daily Leader. Yn anffodus, wyddon ni ddim pryd fu Jane farw, ond gobeithio y bydd y cofiant sydd i ddod gan Jane Aaron yn datgelu mwy. Prin bum mlynedd ynghynt roedd y ddwy yn dal i fyw gyda’i gilydd yn Llangrannog a thŷ yn y dref honno oedd y cyfeiriad a ddefnyddiodd Cranogwen am y rhan fwyaf o’i hoes. Waeth pa mor bell y byddai’n teithio, byddai bob amser yn mynd adref at Jane.

Cofeb i Sarah Jane Rees, Llangrannog (WikiCommons)

[i]Y Gwladgarwr, 5 Mai, 1866

[ii]Baner ac Amserau Cymru, 14 Ebrill 1866

[iii]Cardiff Times, 5 Hydref 1866

[iv]Seren Cymru, 4 Ionawr 1867

[v]Y Tyst Dirwestol Cyf. XIII rhif. 154 - Hydref 1910

[vi]Cambrian Daily Leader, 28 Mehefin 1916