Graham Davies, Digital Programmes Manager, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales

"Content is King". The phrase is strong, infallible, sitting proud on his pedestal, a little like the Queen Mother, or the National Health Service. Sacrosanct. But has the time come to question some of our long held adages in the world of digital content and web design? Is content actually 'King' anymore?

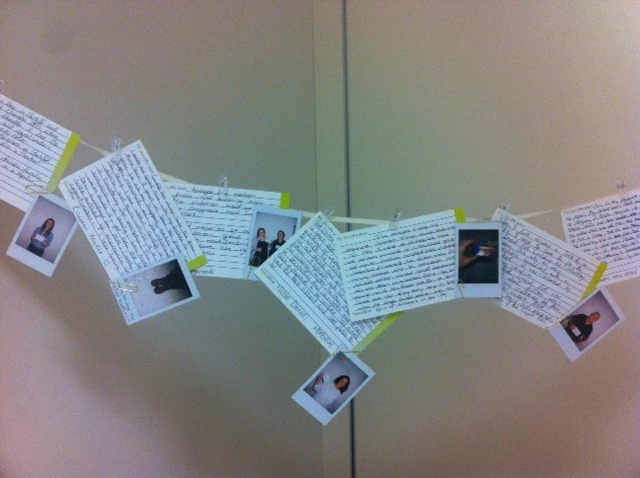

Fresh back from an energising few days with the fab team at Culture24 at the Let's Get Real workshops and conference, I am determined not to let the enthusiasm and momentum get buried by the squillions of things in my inbox that greet me now that I am not 'Out of Office' anymore.

The discussions of the last few days have left me pondering over our constantly evolving digital landscape.

Which direction, and how high do we have to throw our digital content ball to get it successfully into the constantly moving net of engagement?

Jessica Riches, in her talk on 'Learning from Brands' seemed very surprised that she was the first of the day to mention the phrase ‘Content is King’

This made me think. And think again. About the shift in focus to be more about platforms, the importance of audiences and what channels those audiences use and reside in.

So has the time come to update or even rewrite the rulebook?

1. Content is King?

Surely it's not just raw content that is king anymore. Who your content is intended for significantly alters how it should be written and where it should be published. What is the intent of those people reading it? (as apposed to the intentions of those writing it). So I give you rule rewrite number 1:

Content, Intent and Purpose are the new King, Queen and Jack

By thinking of it this way, you are reminded that content on its own doesn't stand any more. It's equally important to also think of why you are writing it and where the people are who want to read it?

2. Build it and They Will Come?

This fell off its pedestal a long time ago, but if we were to prop it back in place the stonemasons would need to re-carve the plinth to read:

Write it and take it to where they are. Or perhaps better still: Go pay them a visit and have a chat

This helps reinforce the idea that we can't be institutional broadcasters anymore, we should be working with our audience to help them answer what they want to know, rather than what we want to tell them.

To demonstrate this, Shelley Bernstein provided us with a superb keynote speech at the Let's Get Real conference on how the Brooklyn Museum are trusting the audience and developing a wholly user-centric approach to their new responsive museum.

3. Design Responsive Websites

Great, Yes, very good. Although a revision of this phrase can encompass web design by default whilst primarily focussing on content:

Optimise your content to be platform independent

4. Think Mobile First

Yes, we must, and we should make this behaviour ingrained. By turning this rule upside-down, our new banner proclaims (and by its very nature automatically assumes mobile first):

Remember to check the desktop

Think back to those good old days where everything had to be retrofitted to work in IE 6. Who now retrospectively checks that everything reads and works well on a desktop? Not many I'm guessing.

But beware. Herein lies the paradox: Remember, people looking to visit one of our venues are more likely to be looking us up through a mobile device. However, people looking at in-depth long-form curatorial and academic material are predominantly still using desktops.

This is where headline metrics can be misleading, if your website as a whole shows a rise in mobile, that doesn't mean that all the content on the site is being accessed through mobiles. This is why metric analysis is so crucial before we apply blanket statements based on overall trends.

This brings me onto to something bigger I have been mulling over recently...

"Can we put it on the website please"?

Quite frankly, I dislike the term "Website". I often ask what section or area people are actually referring to, for websites these days have come to contain many distinct areas and functions, serving completely separate and different audiences and requirements. Maybe this is the crux of the problem? At the moment we are all busy working on a 'one solution fits all approach'. Shouldn't we be thinking of applying separate templates and content strategies based on different audience requirements within our own websites?

Going back to our rewritten rule number one, and this should be applied within (and throughout) our own organisational websites too.

All this can help us ensure that we consistently put the users needs at the centre of our goals and ambitions. Just by thinking a little differently about our assumptions, we have the ability to take a quicker, more direct route to successful engagement.