Virtually cleaning an eighteenth-century painting

, 7 Medi 2011

Graham Davies, Online Curator, Amgeddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

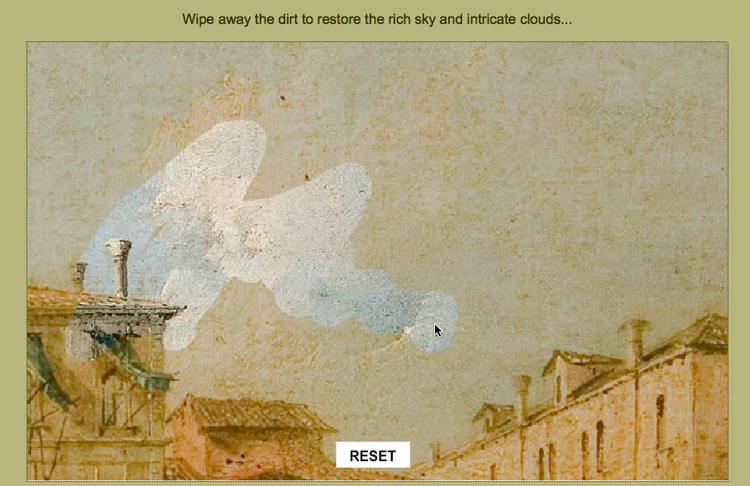

When a member of the Art department approached me to ask if I could feature two views of the same painting online – one version covered in dirt and yellowed varnish (as the painting was when it came into the Museum), and the other version showing hidden detail and crisp colours (after being cleaned by Museum conservators) – I realised it would make a perfect interactive if you could use your mouse to virtually 'clean' the dirty canvas to reveal the clean version underneath.

Guardi's view of the Grand Canal, Venice

The painting in question is Francsesco Guardi's View of the Palazzo Loredan dell'Ambasciatore on the Grand Canal, Venice, painted around 1775-85.

Acquired by Amgueddfa Cymru in 2011, this painting is an important acquisition as Guardi's Venetian views are regarded as highly significant in the history of landscape painting.

You clean the painting

To make the most out of this dramatic before-and-after view, I needed to work out a way of 'virtually' cleaning the painting online by dragging a mouse over the dirty image to reveal the original details and colours previously hidden underneath the dirt and old varnish.

Reinvent the wheel?

I wanted something that allowed the mouse to act as an eraser, allowing one image to be rubbed out to reveal a secondary image underneath. A hunt around the internet brought up the required functionality already created by by Jonathan Nicol (www.f6design.com/journal).

The next step was to acquire high-resolution copies of both dirty (before) and cleaned (after) digital images of the artwork from the Photography department.

Precisely aligning two slightly differently angled photographs of the same picture

When I opened these digital images in Photoshop it became apparent that variations in the perspective, and distance of the photographic captures, resulted in two images that did not precisely match up once overlaid on top of one another.

After an hour of miniscule adjustments using the image warp feature on Photoshop, using the images as separate layers within Photoshop (one set at 50% opacity), I eventually achieved a precise overlaid match.

I abandoned trying to do this at 100% view as the image was so large and the time lag in processing too great to view the results (even for my G5 at 2.44Gz and 8GB RAM). I had to settle for a 25% view that filled my Apple 32" screen)

Once I had a satisfactory matched up and aligned the 'dirty' layer on top of the 'clean' layer, I could create the two corresponding TIFF images to incorporate into the Flash file as a basis for the interactive.

After a bit of tweaking, fiddling, and constant testing, I managed to create a simple interactive, allowing you to use your mouse to erase the dirt and grime, revealing the clean painting underneath.

Exploring the detail

I then decided to repeat this process to create several versions, all using crops of the high-resolution images to show close up details of the painting.

Areas of particular interest I chose to separate out were people rowing a gondola, the architectural detail of the buildings, and the detail of the sky and clouds where much original detail had been almost totally obscured by years of grime, dirt and previous 'touch-ups' to the painting. The clean version revealed original intricate details and brushwork.

Future applications for Museum archives and collections

I am hoping this functionality can be utilised for other online images of the collections in the future. Ideas I have at the moment are to reveal hidden under-drawings only visible under x-ray light — as in the example of Richard Wilson's Dolbadarn Castle (NMW A 72), which has been painted over a portrait of a woman, and Landscape with Banditti around a Tent (NMW A 69) which he painted over a Venetian-style reclining nude.

Additional ideas include viewing a landscape or post-industrial townscape that can be erased to reveal a historical image underneath...

![Golygfa o'r Palazzo Loredan dell'Ambasciatore ar y Gamlas Fawr yn Fenis [cyn glanhau]](/media/14015/version-full/dirty_guardi.webp)

![Golygfa o'r Palazzo Loredan dell'Ambasciatore ar y Gamlas Fawr yn Fenis [wedi glanhau]](/media/14016/version-full/clean_guardi.webp)