Yr Amgueddfa Wlân Genedlaethol yn Gwehyddu'r Dyfodol

, 26 Chwefror 2020

Mae gwlân yn cael ei ddathlu fel ffibr hollol naturiol, cynaladwy a bioddiraddadwy'r dyfodol. Mewn oes lle mae'n rhaid i ni gwestiynu'r effaith y mae ffasiwn gyflym yn ei gael ar y blaned, mae nifer cynyddol ohonom yn dychwelyd i ffibrau naturiol – nid dim ond ar gyfer dillad, ond hefyd i inswleiddio a dodrefnu eu cartref. Mae gwarchod sgiliau traddodiadol yn rhan bwysig o waith Amgueddfa Cymru, ond gyda'r diddordeb cynyddol hwn mewn ffibrau naturiol a chynaliadwy, yn ogystal â'r ymchwydd mewn ffasiwn a thecstilau cartref, mae’r sgiliau yma a gysidrwyd am flynyddoedd yn 'grefftau treftadaeth ' nawr yn datblygu'n sgiliau pwysig ar gyfer ein dyfodol.

Mae ymwelwyr â'r Amgueddfa Wlân Genedlaethol yn Dre-fach Felindre eisoes yn mwynhau gwylio meistr wehyddwyr Melin Teifi, Melin wlân fasnachol sy'n denantiaid yn yr Amgueddfa, yn gwehyddu ffabrigau hardd mewn patrymau traddodiadol ar wyddau mecanyddol. Maen nhw'n darparu cipolwg diddorol i’n hymwelwyr ar waith a phrosesau melin weithiol. Ond yn anffodus, Melin Teifi yw'r felin wlân olaf yng Nghymru sy'n cynhyrchu gwlanen draddodiadol Gymreig. Yn anterth y diwydiant yn yr ugeinfed ganrif roedd 217 o felinau gwlân yng Nghymru, yn bennaf yn cynhyrchu carthenni Cymreig, gwlanen a brethyn tapestri. Ar hyn o bryd mae 7 i 8 o felinau gwlân yn gweithredu yng Nghymru, ac mae perygl difrifol na fydd y sgiliau hyn yn cael eu cynnal ar gyfer y dyfodol, oni wneir ymdrech gydunol. Dyna pam y mae Amgueddfa Cymru yn arbennig o falch i groesawu tri chrefftwr newydd dan hyfforddiant i'n tîm yn yr Amgueddfa Wlân Genedlaethol. Ymunodd James Whittall, Jay Jones a Richard Collins a ni ym mis Rhagfyr ac maent eisoes wedi dechrau ar eu hyfforddiant mewn sgiliau crefftau treftadaeth. Yn ddiweddar, maen nhw wedi dechrau arddangos rhai o'u sgiliau crefft llaw newydd, i'n hymwelwyr. Mae hyn yn ein helpu i ddod â stori'r diwydiant gwlân a chasgliad yr Amgueddfa yn fyw. Wrth iddyn nhw ddatblygu sgiliau gwehyddu dros y misoedd a'r blynyddoedd nesaf, y gobaith yw y byddant hefyd yn ein helpu i gyflawni rhywfaint o'r galw cynyddol am gynnyrch wedi ei wreiddio mewn traddodiad, a datblygu gweithgaredd masnachol newydd ar gyfer yr Amgueddfa.

Gallai gweithgaredd o'r fath gefnogi ein heconomi wledig ac ysgogi cyfleoedd i'n pobl ifanc wireddu'r potensial o ennill gwaith a bywydau boddhaus yn yr ardal, gyda'r fantais ychwanegol o gefnogi cynhaliaeth a datblygiad y Gymraeg. Mae tirwedd y diwydiant gwlân yng Nghymru yn debygol o newid dros y blynyddoedd nesaf, ac mae potensial i dwf 'melinau meicro', yn ddibynnol ar sgiliau traddodiadol yn cael eu cadw i alluogi cyflenwi i ddylunwyr Cymreig. Rydym yn falch iawn o fod yn chwarae ein rhan i adfer y sgiliau gwerthfawr hyn i gefnogi adfywio'r hyn sydd yn hanesyddol wedi bod yn un o ddiwydiannau pwysicaf Cymru.

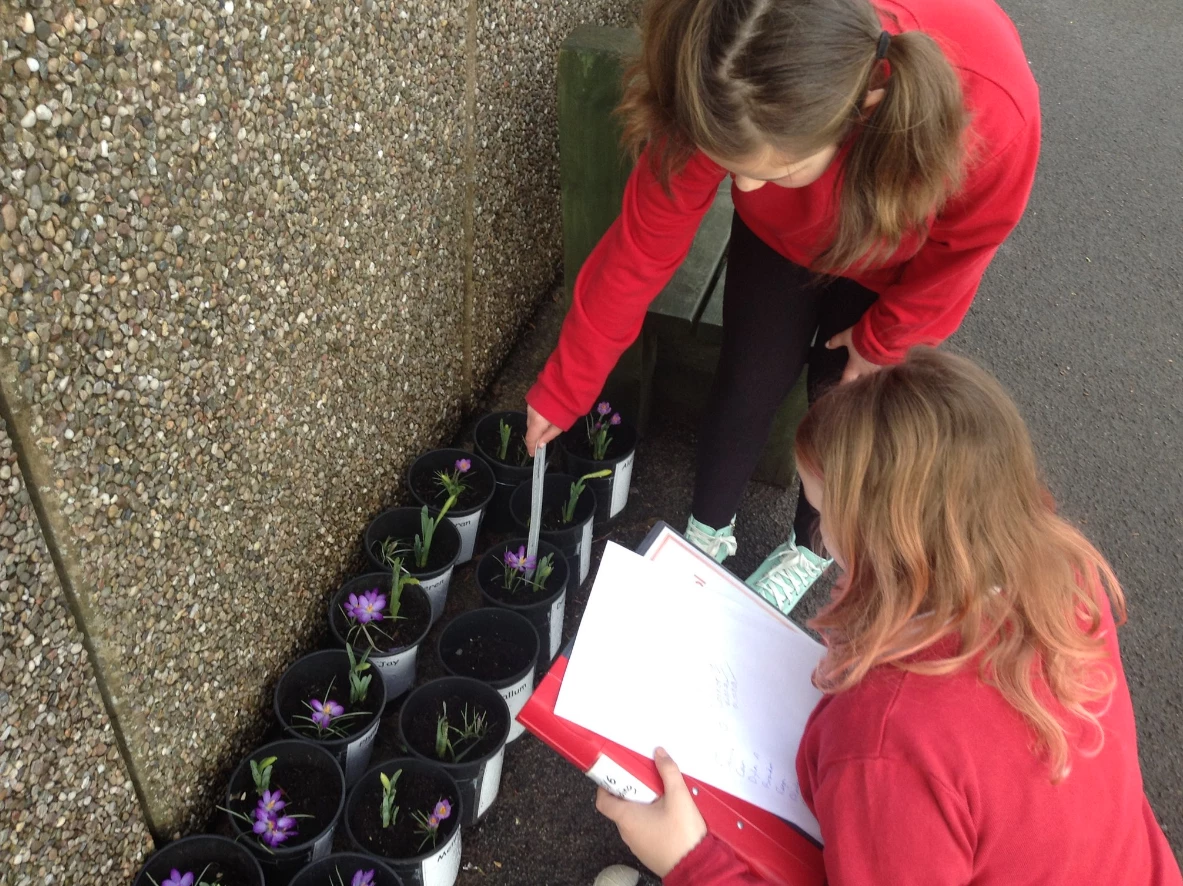

Richard Collins, Crefftwr o dan Hyfforddiant, yn dysgu nyddu ar y droell nyddu.

BBC Radio Wales Rhaglen Roy Noble 01/03/2020: Crefftwyr newydd Amgueddfa Wlân Cymru

(Gwrandewch o 1:12:00)