Heddiw – 8 Mawrth – mae amgueddfeydd ac archifdai ledled Cymru yn dathlu Diwrnod Rhyngwladol y Menywod. #BeBoldForChange yw’r thema eleni – neges amserol, gwta chwe wythnos wedi’r orymdaith fawr yn Washington DC a thu hwnt. Yn y blog hwn, mi fydda i’n trafod gwrthrych o’r casgliad sy’n amlygu ysbryd debyg ar waith yn 1911-13 – sef baner a ddefnyddiwyd gan y Cardiff & District Women’s Suffrage Society i fynnu’r bleidlais i fenywod.

Dull di-drais

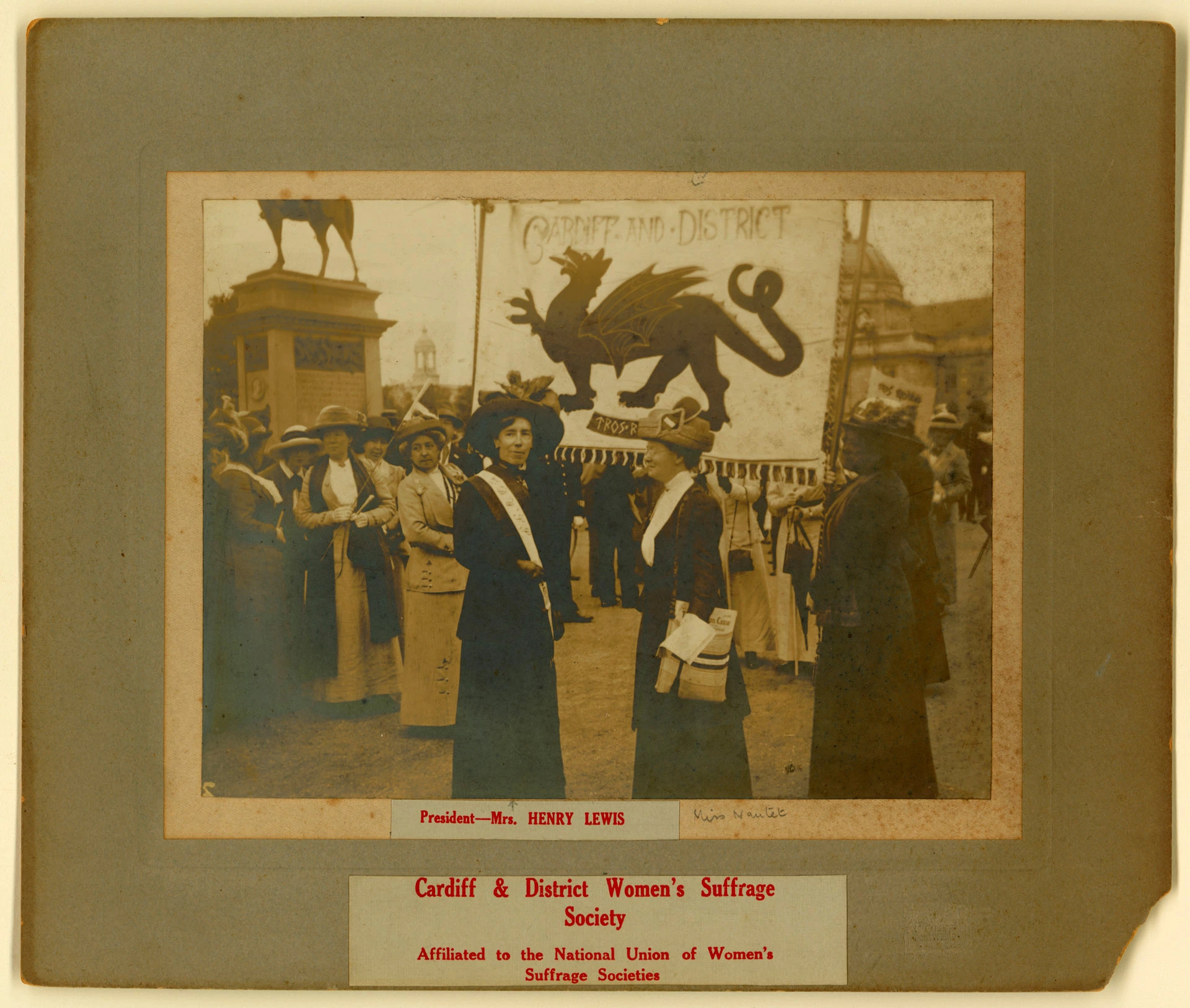

Er mai hynt a helynt y swffragetiaid oedd yn hawlio sylw’r wasg, roedd mwy o lawer o ‘suffragists’ yn bodoli yng Nghymru. Roedd y ‘suffragists’ yn credu mewn gweithredu heddychlon a newid y drefn drwy ddulliau cyfansoddiadol. Yn eu plith, roedd aelodau’r Cardiff & District Women’s Suffrage Society. Hon oedd y gangen fwyaf o’r National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies tu allan i Lundain. Rose Mabel Lewis (Greenmeadow, Tongwynlais) oedd wrth y llyw yng Nghaerdydd – neu Mrs Henry Lewis fel y cyfeirir ati yn nogfennaeth yr Amgueddfa! Yn gyffredinol, roedd aelodau blaenllaw'r gangen yn fenywod dosbarth canol a oedd yn adnabyddus o fewn mudiadau a chylchoedd cymdeithasol y ddinas. I godi ymwybyddiaeth o’u hachos ac i lenwi coffrau’r gangen, roedden nhw’n cynnal digwyddiadau ac yn gwerthu copïau o gylchgrawn y mudiad, The Common Cause. Mae adroddiad blynyddol y gangen ar gyfer 1911-12 yn rhestru gweithgareddau di-ri, yn eu plith dawns gwisg ffansi, gyrfa chwist a ffair sborion. Yn y flwyddyn honno, dyblodd nifer aelodau’r gangen i 920.

Crefft ymgyrchu

Rose Mabel Lewis bwythodd y faner sidan sydd bellach yng nghasgliad yr Amgueddfa – enghraifft bwerus o rym y nodwydd fel arf i ledaenu neges ac i fynegi barn. Er nad ydym yn gwybod union ddyddiad y faner, rydym yn sicr iddi gael ei defnyddio mewn protest yn 1911. Ar 17 Mehefin y flwyddyn honno, arweiniodd Rose Mabel fenywod de Cymru yn y Women’s Coronation Procession yn Llundain. Mae dogfennau derbynodi’r faner yn cynnwys nodyn o eglurhad gan un o gyn-aelodau’r gangen:

The banner was worked by Mrs Henry Lewis… [she] was also President of the South Wales Federation of Women’s Suffrage Societies + she led the S. Wales section of the great Suffrage Procession in London on June 17th 1911, walking in front of her own beautiful banner… It was a great occasion, some 40,000 to 50,000 men + women taking part in the walk from Whitehall through Pall Mall, St James’s Street + Piccadilly to the Albert Hall. The dragon attracted much attention – “Here comes the Devil” was the greeting of one group of on lookers”.

Roedd baneri fel hyn yn rhan ganolog o ddiwylliant gweledol y mudiad pleidlais i fenywod, ac mae nifer ohonynt i'w canfod mewn amgueddfeydd ac archifdai, gan gynnwys Casgliadau Arbennig ac Archifau Prifysgol Caerdydd. Roedd trefnwyr gorymdaith fawr 1911 yn disgwyl dros 900 o faneri ar y dydd!

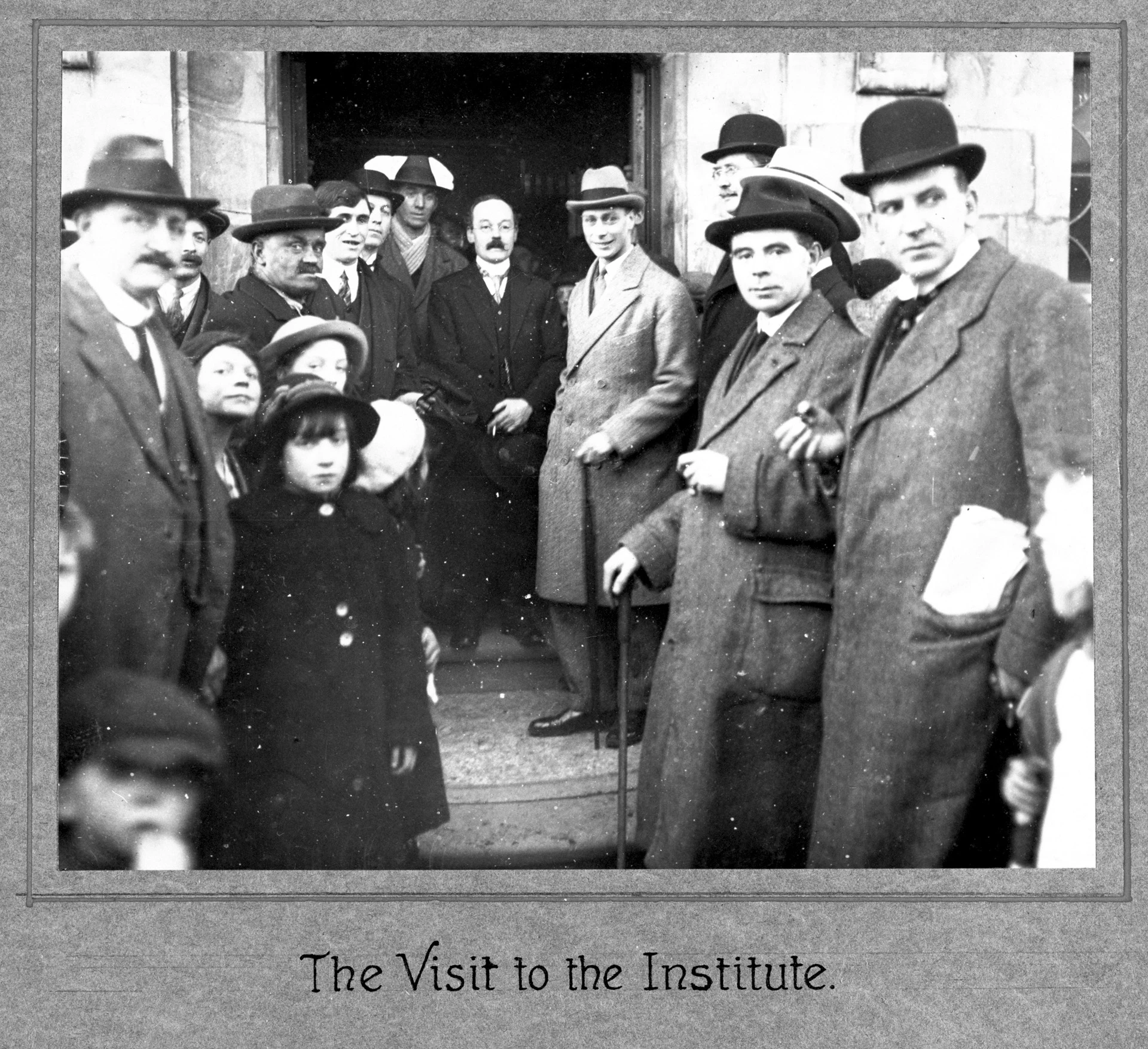

Dwy flynedd yn ddiweddarach, yng Ngorffennaf 1913, gwelwyd y faner ar strydoedd Caerdydd fel rhan o orymdaith yn y brifddinas i nodi’r Bererindod Fawr i Lundain (the Great Suffrage Pilgrimage). Mae casgliad yr Amgueddfa yn cynnwys lluniau anhygoel o Rose Mabel Lewis, ac aelodau eraill y gangen, wedi ymgynnull gyda’r faner tu allan i Neuadd y Ddinas ym Marc Cathays. Yn ôl adroddiad blynyddol 1913-14, roedd rhai o’r aelodau yn betrusgar ynglyn â’r orymdaith, ond wedi eu bywiogi ar ôl derbyn ymateb ffafriol ar y dydd:

It was with misgivings that some members agreed to take part in the procession, but afterwards their enthusiasm aroused and the desire to do something more in the future. The march was useful in drawing the attention of many people to the existance of our society.

Creu Hanes a’r canmlwyddiant

Yn 2018, bydd y faner i’w gweld yng Nghaerdydd unwaith eto – nid mewn rali y tro hwn, ond ymhlith llwyth o wrthrychau arwyddocaol yn ein hanes cenedlaethol fydd i’w canfod mewn oriel newydd yma yn yr Amgueddfa Werin – penllanw ein prosiect ail-ddatblygu, Creu Hanes. Cyd-ddigwyddiad amserol gan fod 2018 yn nodi canmlwyddiant Deddf Cynrychiolaeth y Bobl 1918. Hyd y gwn i, nid yw'r faner wedi bod ar arddangos ers iddi gael ei rhoi i'r casgliad yn 1950 gan y Cardiff Women Citizens' Association. Ar y pryd, ysgrifennodd drysorydd y gymdeithas honno lythyr at Dr Iorwerth Peate yn mynegi eu balchder fod y faner bellach ar gof a chadw yn Sain Ffagan:

A cordial vote of thanks was accorded to you for realising how much the Suffrage Cause meant to women and for granting a memorial of it in the shape of the banner to remain in the Museum.

Elen Phillips @StFagansTextile

Ffynonellau cynradd:

National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies: Cardiff & District Annual Report, 1911-12 (Amgueddfa Werin Cymru).

National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies: Cardiff & District Annual Report, 1913-14 (Amgueddfa Werin Cymru).

Dogfennau derbynodi 50.118 (Amgueddfa Werin Cymru).

Ffynonellau eilradd:

Kay Cook a Neil Evans, 'The Petty Antics of the Bell-Ringing Boisterous Band'? The Women's Suffrage Movement in Wales, 1890 - 1918' yn Angela V. John (gol.), Our Mothers' Land Chapters in Welsh Women's History 1830 - 1939 (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 1991).

Ryland Wallace, The Women's Suffrage Movement in Wales 1866 - 1928 (Caerdydd: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, 2009).