Beth wnaethoch chi yn ystod y Cyfnod Clo? Wnaethoch chi fwynhau byd natur, a gweld pethau newydd wrth gerdded eich milltir sgwâr bob dydd? Dyna wnaeth dau o Gymrodorion Ymchwil Anrhydeddus yr Amgueddfa, Dr Joe Botting a Dr Lucy Muir, a chanfod trysorfa o ffosilau newydd ger eu cartref yn y canolbarth. Doedd y ddau ymchwilydd annibynnol yn methu teithio i Amgueddfa Cymru i barhau â’u gwaith ar fywyd hynafol, felly dyma nhw’n defnyddio cyllido torfol i brynu microsgopau er mwyn astudio eu canfyddiadau newydd yn fanwl. Mae’r ffosilau’n perthyn i sawl grŵp anifeiliaid gwahanol, gan gynnwys rhai sydd bron byth yn ffurfio ffosilau am fod ganddynt gyrff meddal, heb gregyn, esgyrn na dannedd. Mae Joe a Lucy yn cydweithio gyda phalaeontolegwyr o bob cwr o’r byd i astudio ffosilau a dehongli’r hyn allan nhw ei ddatgelu am fywyd ym moroedd Cymru dros 460 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl.

Mewn erthygl a gyhoeddwyd heddiw yng nghyfnodolyn Nature Communications – dan arweiniad Dr Stephen Pates o Brifysgol Caergrawnt a gyda chymorth Dr Joanna Wolfe o Brifysgol Harvard, mae Joe, Lucy a’u cydweithwyr yn disgrifio dau ffosil anarferol o’r safle newydd. Ffosilau ydyn nhw o anifeiliaid bach iawn, meddalgorff, sy’n debyg i greadur rhyfedd o’r enw Opabinia, oedd yn byw yng Nghanada dros 40 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl. Disgrifiwyd anifail tebyg o’r enw Utaurora mewn creigiau o oed tebyg yn UDA. Wyddon ni ddim os yw’r ffosilau o Gymru yn perthyn i’r un teulu o anifeiliaid a ganfuwyd yng Ngogledd America, ond maen nhw’n sicr yn dangos fod anifeiliaid rhyfedd, tebyg i opabiniidau yn byw yn y moroedd yn llawer hirach nag oedden ni’n ei gredu, a dros ardal ddaearyddol fwy.

O ble mae’r ffosilau’n dod?

Cafodd y ffosilau eu canfod mewn chwarel ar dir preifat ger Llandrindod (mae’r union leoliad yn gyfrinach er mwyn gwarchod y safle). Cafodd y ffosilau eu canfod mewn creigiau a ddyddodwyd dan y môr yn y cyfnod Ordoficaidd, dros 460 miliwn o flynyddoedd yn ôl, pan oedd canolbarth Cymru dan ddŵr gydag ambell i ynys folcanig fan hyn a fan draw.

Pa fath o anifeiliaid oedden nhw?

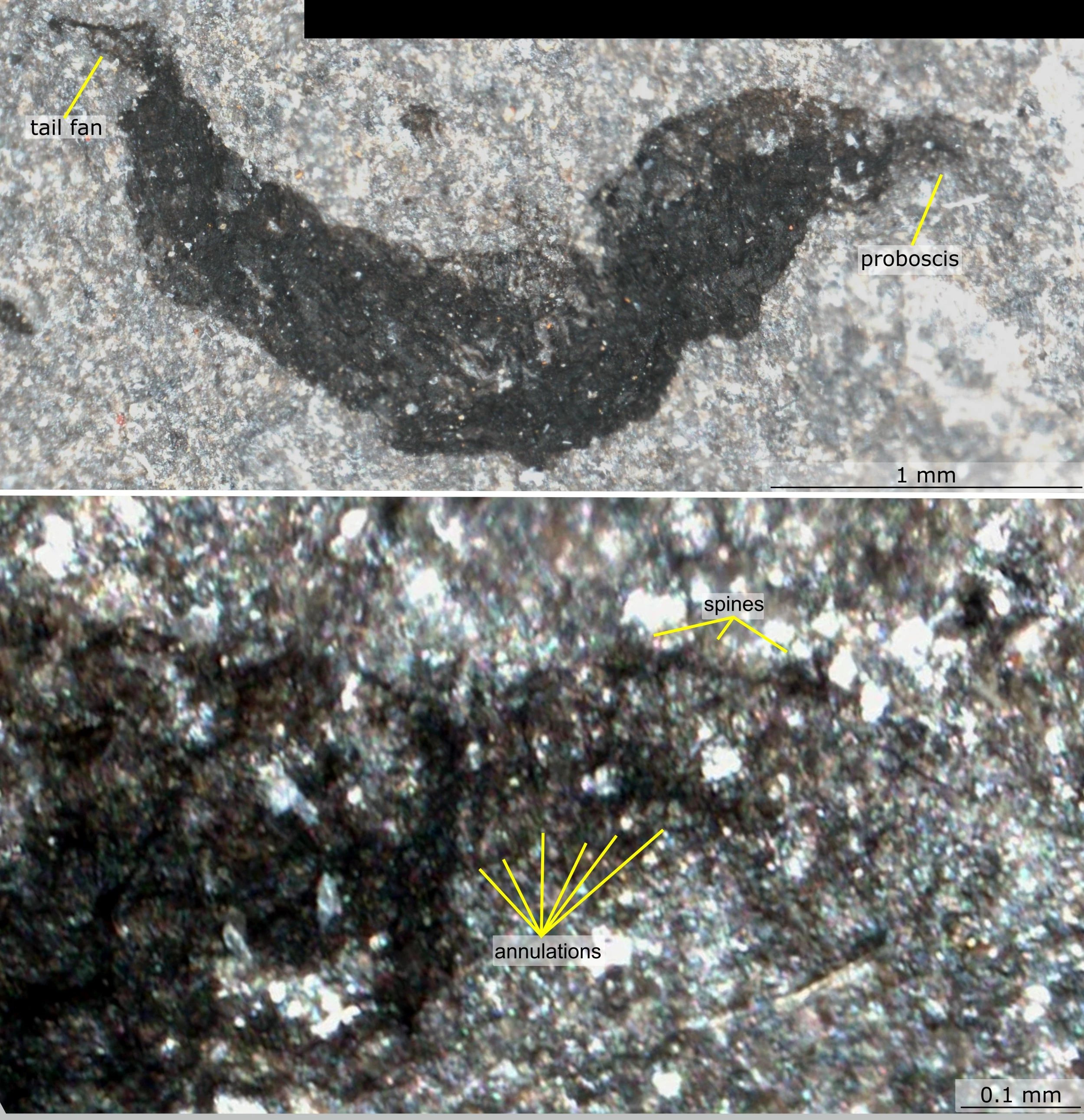

Mae’r ffosilau o Gymru yn edrych fel ‘opabiniidau’ – anifeiliaid rhyfedd oedd i’w gweld cyn hyn mewn creigiau Cambriaidd llawer hŷn yn unig. Anifeiliaid morol oedd Opabiniidau, gyda chyrff meddal a bongorff tenau gyda rhes o fflapiau ar y ddwy ochr (ar gyfer nofio mae’n bosib) a phâr o goesau trionglog cwta oddi tanynt. Ar un pen i’r bongorff roedd cynffon fel gwyntyll.

Ar y pen arall roedd eu nodwedd amlycaf – proboscis, neu dduryn hir yn ymestyn o’r pen, fel rhyw fath o sugnydd llwch. Yn wahanol i’r Opabiniidau Cambriaidd, mae rhes o bigau bach ar broboscis y rhywogaeth o Gymru. Y gred yw bod y proboscis yn hyblyg, ac efallai’n cael ei ddefnyddio i gasglu bwyd o wely’r môr a’i symud at y geg, oedd y tu ôl i’r proboscis ar ochr isaf y pen. Roedd y coesau a’r proboscis yn gylchog, gyda nifer o segmentau fel modrwyau. Ond doedd y rhain ddim yn ‘gymalog’, yn yr un modd ag y mae coesau cranc neu gorryn yn gymalog. Y gred yw bod opabiniidau yn rhannu’r un cyndadau ag anifeiliaid coesau cymalog modern o’r enw ‘arthropodau’, heb fod yn gyndeidiau uniongyrchol.

Mae’r mwyaf o’r ddau ffosil yn 13mm o hyd, gan gynnwys y proboscis 3mm. Mae’r lleiaf yn 3mm o hyd, gyda’r proboscis bron i draean o’i holl hyd. Mae rhai gwahaniaethau rhwng y ddau ffosil, sy’n awgrymu bod y lleiaf yn fersiwn iau o’r sbesimen mwy, neu efallai’n rhywogaeth hollol wahanol. Ond mae’r ddau sbesimen o Gymru yn llawer llai na Opabinia, sydd â ffosilau hyd at 7cm o hyd.

Enw Cymreig i ryfeddod Cymreig!

(Mae gan bob rhywogaeth, boed yn fyw neu wedi marw allan, enw gwyddonol mewn dwy ran – enw genws ac enw rhywogaeth. Yr enw gwyddonol a ddewiswyd ar gyfer un o’r anifeiliaid ffosil yw Mieridduryn bonniae. Enwyd y rhywogaeth ar ôl Bonnie, nith perchnogion y tir lle canfuwyd y ffosilau, i ddiolch i’r teulu am eu cefnogaeth a’u brwdfrydedd yn ystod y gwaith ymchwil. Mae’n eithaf cyffredin i rywogaethau newydd gael eu henwi ar ôl y bobl wnaeth eu darganfod, neu sydd wedi gwneud llawer o waith ar rywogaethau tebyg. Daw enw’r genus drwy gyfuno’r geiriau Cymraeg mieri a duryn (proboscis). Ysbrydolwyd hyn gan y rhes o bigau, tebyg i fieri, ar hyd proboscis yr anifail. Mae’n anarferol i enw gwyddonol gael ei seilio ar y Gymraeg – geiriau Lladin neu Groeg yw gwreiddyn y rhan fwyaf. Bydd yr enw Mieridduryn yn dyst i’r ffosil gael ei ddarganfod yng Nghymru.

Penderfynwyd nad oedd yr ail ffosil wedi ei gadw’n ddigon da i’w gydnabod yn rhan o’r un rhywogaeth, neu ei enwi fel rhywogaeth wahanol.

Beth alla i wneud os ydw i’n canfod ffosil anarferol?

Mae’r ffosilau hyn yn dangos fod llawer o bethau newydd, cyffrous i’w canfod yng Nghymru. Os ydych chi’n canfod rhywbeth diddorol a ddim yn siŵr beth yw e, bydd gwyddonwyr yr amgueddfa yn barod i geisio ei adnabod i chi, boed yn ffosil, carreg, mwyn, anifail neu blaned. Anfonwch ffotograff aton ni (gyda cheiniog neu bren mesur i ddangos y maint) a manylion ble wnaethoch chi ei ganfod. E-bostiwch ni drwy wefan yr Amgueddfa neu drwy Twitter @CardiffCurator. Mae sawl Taflen Sylwi ar ein gwefan hefyd, fydd yn eich helpu i adnabod rhai o’r gwrthrychau mwyaf cyffredin.