Sefydlwyd fforymau yn gynnar yn y project Creu Hanes yn Sain Ffagan i'n helpu ni i ddatblygu ein harferion cyfranogi. Un o'r fforymau hyn oedd y Fforwm Dysgu Anffurfiol, a'i ffocws oedd ar ddysgu i oedolion a'r gymuned a'u cyfranogiad. Roedd y partneriaid ar y fforwm hwn yn gysylltiedig â'r meysydd gwaith hyn yn bennaf a daethant ynghyd i'n cynorthwyo ni i ddatblygu rhaglen addysg i oedolion yn yr Amgueddfa.

Yn ystod y project, chwaraeodd y Fforymau rolau gwahanol, ac roedd rhai yn fwy gweithredol nag eraill. Gweithiodd y Fforwm Dysgu Anffurfiol gyda ni cryn dipyn ar y dechrau ac yna drwy gydol oes y project, ac roedden nhw'n gyfrifol am helpu i lunio cwmpas maes Dysgu Oedolion yn yr Amgueddfa.

Yn 2015, pan ddechreues i weithio gyda'r fforwm fe aethon ni ati i ailystyried eu rôl ac adfywio eu rhan nid yn unig yn y project ond ym maes Addysg Oedolion drwy'r Amgueddfa, yn ogystal â chyfrannu at ddatblygiad y rhaglen Llesiant.

Ers hynny mae'r fforwm, sy’n dwyn y teitl Fforwm Addysg Oedolion bellach, wedi mynd o nerth i nerth. Maen nhw wedi'n helpu ni drwy'r project a gyda gwaith newydd a gwaith sy’n mynd rhagddo. Mae llawer o'r partneriaid gwreiddiol yn parhau gyda ni ers cwblhau'r project yn 2018, ac mae partneriaid newydd wedi ymuno ers hynny, gan ychwanegu at amrywiaeth ac ehanger y grŵp.

Dyma flas o rywfaint o'r gwaith rydyn ni wedi'i wneud gyda'n gilydd dros y blynyddoedd a'r hyn sydd gan bartneriaid i'w ddweud:

"Roedd hi'n fraint i Llandaf 50+ gael gwahoddiad i ymuno â'r Fforwm Addysg i Oedolion a mynychu ei gyfarfodydd chwarterol yn yr Amgueddfa Werin.

Amcanion ein helusen yw helpu i leddfu problemau unigedd ac ynysu cymdeithasol ymhlith pobl hŷn, a'u hannog nhw i drefnu, a chymryd rhan mewn gweithgareddau a digwyddiadau cymdeithasol. Felly, roedd gweithio gyda Sain Ffagan, a sefydliadau a grwpiau elusennol lleol yn gyfle heb ei ail. Fe arweiniodd y cyfle i gyfrannu at drafodaethau ynghylch cyfleusterau a chyfleoedd i bobl hŷn yn ystod aildrefnu'r Amgueddfa at lawer o awgrymiadau gan ein haelodau ynghylch problemau bod yn hŷn.

Mae'n hawdd iawn canolbwyntio ar eich sefydliad chi'ch hun heb fod yn ymwybodol o'r hyn sy'n digwydd yn y sector gwirfoddol ac elusennol. Er bod gennym gyfle i roi diweddariad ar ein gweithgareddau ni yn y Fforwm, mae'n wych clywed beth arall sy'n digwydd. Ac rydyn ni hefyd yn cael cyfle i gwrdd â phobl newydd o ardal Caerdydd a'r Fro, pobl sy'n helpu eraill i wella eu bywydau. Yn ôl ein Trysorydd ar ôl ei chyfarfod cyntaf: 'doeddwn i ddim yn sylweddoli bod cymaint yn digwydd, mae pobl yn gwneud pethau gwych'.

Ac rydyn ni'n clywed am gyfleoedd i wirfoddoli hefyd. Mae gennym atgofion melys o gatalogio llyfrau o hen lyfrgell Sefydliad y Gweithwyr Oakdale, a'u gweld nhw yn ôl ar y silffoedd lle dylen nhw fod. Y llyfrau ar beirianneg, oedd yn ehangu'r meddwl, clasuron y plant i'w diddanu amser gwely, a hyd yn oed rhai a oedd ychydig yn feiddgar (ac yn boblogaidd hefyd o weld y stampiau y tu mewn i'r clawr!). Ac yna ginio pleserus, ar ôl pob sesiwn yn arwain at greu cyfeillgarwch am oes.

Mae'r Fforwm wedi gwneud i Llandaf 50+ deimlo fel rhan o'r Amgueddfa ac fe ddenodd ein hymweliad a thaith i'r Amgueddfa niferoedd gwych o'n haelodau, pawb yn ailymweld gyda ffrindiau newydd ac yn mwynhau esboniadau'r tywyswyr hyddysg. Dychwelodd nifer ohonynt gyda'u teuluoedd yn nes ymlaen yn y flwyddyn i sôn am yr hyn a ddysgwyd.

Rydyn ni hefyd yn gallu trosglwyddo'r wybodaeth rydyn ni'n dysgu amdani yn y Fforwm i'n haelodau. Aeth nifer ohonynt i ddigwyddiadau yn ystod Wythnos Addysg Oedolion gan fwynhau crefftau newydd a hel atgofion am yr hen rai. Caiff teithiau cerdded newydd a thaflenni eu hegluro yn ystod cyfarfodydd 50+ ac rydyn ni'n annog pobl i ymweld.

Gobeithio bydd y Fforwm yn parhau i alluogi ein helusen, fechan ond gweithgar, i weithio gydag Amgueddfa mor bwysig a phoblogaidd yn y dyfodol, er lles pawb." (Gwirfoddolwr, Llandaf 50+)

Project Ail-ddehongli Sefydliad y Gweithwyr Oakdale

Roedd aelodau'r fforwm yn hanfodol i'r gwaith o ail-ddehongli Sefydliad y Gweithwyr Oakdale yn ystod 2015-16. Yn sgil eu cyfraniad nhw, gwelwyd yr adeilad yn ailagor gyda dehongliad mwy cyfranogol a chyfeillgar i'r defnyddiwr. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys datblygu adnoddau i ddysgwyr Cymraeg, pobl sy'n byw gyda dementia ac unigolion gyda chyflyrau synhwyraidd. Gallwch nawr fynd i mewn i bob un o ystafelloedd y sefydliad - o'r blaen dim ond cip drwy'r drws oedd yn bosibl cyn y gwaith ail-ddehongli.

"Ym mis Mawrth 2016, fel aelod o grŵp Hanes Lleol Prifysgol y Drydedd Oes yng Nghaerdydd, fe gymerais i ran ym mhroject ail-ddehongli Sefydliad y Gweithwyr Oakdale, neu'r 'stiwt' fel y byddai'r trigolion lleol yn ei alw. Fel rhan o’r project, bûm i'n ymchwilio i'r adeilad, a godwyd yn ystod y Rhyfel Mawr, ac a barhaodd i fod yn ganolfan gymdeithasol ac addysgiadol allweddol i lowyr yr Oakdale a'r gymuned ei hun drwy'r ystafell darllen, cyfarfodydd, y llyfrgell, cyngherddau, ffilmiau a dawnsfeydd am sawl blwyddyn wedi hynny. Penllanw'r project oedd ailagor yr adeilad yn ystod ei flwyddyn ganmlwyddiant, a ddathlwyd gyda pharti i bobl leol o Oakdale gyda minnau'n ysgrifennu erthygl yng nghylchgrawn chwarterol cenedlaethol P3O 'Third Age Matters'. (Valerie Maidment, U3A Caerdydd).

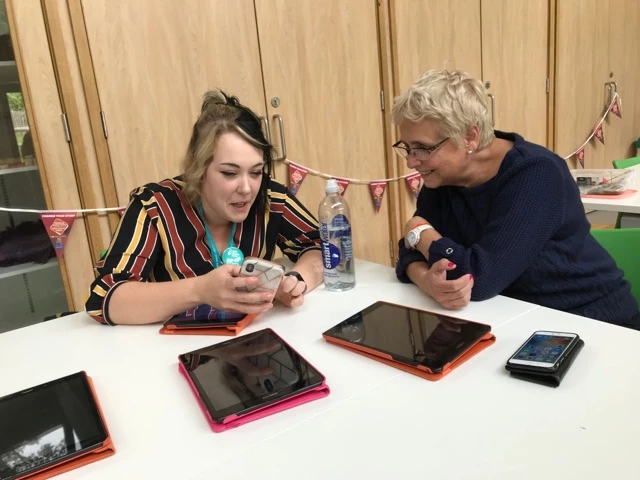

Treialu Addysg Oedolion yn Sain Ffagan

Mae aelodau'r Fforwm wedi bod yn ganolog i dreialu cyrsiau a sesiynau blasu yn Sain Ffagan dros y blynyddoedd diwethaf. Fe wnaethon ni weithio gyda phartneriaid cymunedol lleol Action Ely Caerau (ACE) i recriwtio gwirfoddolwyr i beilota ein cwrs achrededig cyntaf mewn sgiliau gwnïo yn 2016. Roedd yr holl gyfranogwyr yn lleol i'r ardal ac yn wynebu rhwystrau o ran cymryd rhan mewn cyfleoedd dysgu traddodiadol. Roedd y cwrs ynghlwm â'r Amgueddfa ei hun gan fod y cyfranogwyr yn gwneud gwisgoedd i staff yr Amgueddfa eu gwisgo wrth gyflwyno sesiwn yr Oes Haearn i ysgolion. Roedd y gwisgoedd yn seiliedig ar batrwm traddodiadol, a rhoddwyd arweiniad i'r cyfranogwyr ynghylch y technegau yr oedd eu hangen i'w gwneud gan y tiwtor profiadol a'r wniadwraig gwisgoedd hanesyddol arbenigol, Sally Pointer. Doedd dim un o'r cyfranogwyr wedi gwnïo o'r blaen ac fe adawodd pawb ar ddiwedd y cwrs 10 wythnos, nid yn unig â chymhwyster yn eu meddiant, ond wedi gwella eu hyder a'u diddordeb ar gyfer dysgu pellach.

“Rydyn ni wir wedi mwynhau gweithio gyda'r Amgueddfa Werin ac maen nhw wedi dod yn bartner hynod werthfawr ym Mhroject Bryngaer Cudd CAER. Enghraifft o ddylanwad y bartneriaeth hon yw'r cwrs gwnïo a drefnwyd ar y cyd. Mae'r cwrs wedi'i achredu gan Agored Cymru ac yn cael ei gynnal mewn partneriaeth ag Addysg Oedolion Cymru ac mae'r project wedi'i seilio ar gryfderau'r ddau sefydliad gydag Addysg Oedolion Cymru yn recriwtio cyfranogwyr o'n cymunedau lleol (ac yn cynnal yr hyfforddiant yn yr hyb cymunedol lleol). Mae'r Amgueddfa Genedlaethol wedi creu amgylchedd croesawgar gan hwyluso'r hyfforddiant a threfnu ymweliadau i'r ymwelwyr â Sain Ffagan. Cwblhawyd y cwrs gan y 13 o gyfranogwyr, oedd yn wynebu rhwystrau rhag dysgu a’r un ohonyn nhw wedi gwnïo o'r blaen. Ymhlith y canlyniadau roedd gwell hunanhyder a diddordeb o'r newydd mewn dysgu. Mae'r amgueddfa'n parhau i ddefnyddio gwisgoedd yr Oes Haearn a wnaed ganddyn nhw, felly maen nhw wedi llwyddo i wneud eu marc! Rydyn ni wrth ein bodd gyda'r math hwn o broject ac yn gyfranogwyr brwd yn y Fforwm Addysg Oedolion er mwyn sicrhau y gallwn ni barhau i weithio gyda phartneriaid fel yr Amgueddfa Genedlaethol ar y math hwn o broject yn y dyfodol." Dave Horton, Rheolwr Datblygu ACE.

Wythnos Addysg Oedolion:

Mae un o aelodau allweddol y Fforwm, y Sefydliad Dysgu a Gwaith, yn cynnal ymgyrch Wythnos Addysg Oedolion ledled Cymru bob blwyddyn. Maen nhw wedi cynnig cefnogaeth o ran datblygu a chyflwyno ein rhaglenni dros y blynyddoedd ac rydyn ni wedi bod yn gyfranogwyr rheolaidd ers 2015. Rydyn ni wedi profi gweithgareddau a gweithdai crefft, wedi ymchwilio i'r potensial o gyd-gyflwyno a chynnal cyrsiau, ac wedi sicrhau ein bod wedi gallu cynnig cyfleoedd i gyfranogwyr ein sefydliadau partner, yn ogystal â chynnig cyfleoedd ar raddfa ehangach, er enghraifft, drwy gynnal ffair wybodaeth yn 2019. Eleni, ar gyfer Wythnos Addysg Oedolion, rydyn ni wedi bod yn falch i gymryd rhan yn y digwyddiad digidol hwn, gan greu rhaglen o gyfleoedd yn seiliedig ar wneud, ar grefftio ac ar greu.

Dyma ddyfyniad o un o'n partneriaid allweddol, Hafal. Mae cyfranogwyr Hafal wedi treialu a chymryd rhan mewn gweithdai yn ystod Wythnosau Addysg Oedolion blaenorol ac ar wahanol adegau gydol y flwyddyn.

"Rwy'n cynnal project garddio i grwpiau o bobl yn Hafal, yr Elusen Iechyd Meddwl a leolir yn Amgueddfa Werin Cymru Sain Ffagan.

Mae bod yn rhan o'r Fforwm Addysg Oedolion wedi rhoi cyfle anhygoel i mi fynd â grwpiau i amrywiaeth o weithdai a gynhelir yn yr amgueddfa. Roedd y gweithdy Copr Addurniadol yn llwyddiant ysgubol, yn yr un modd â'r gweithdy cerfio llwy garu, ac fe wnaethon ni weithio am sawl wythnos yn helpu gyda tho gwellt yr adeilad to crwn.

Mae cael gwybod gan aelodau eraill y fforwm am yr hyn sydd ganddyn nhw ar y gweill yn y gymuned hefyd wedi cynnig cyfleoedd i ni fynychu gweithgareddau gwahanol. Un o'r rhain oedd y gloddfa archeolegol ym Mryngaer Trelái, lle cawson ni daith o amgylch y safle a gweld rhai o'r arteffactau oedd yn cael eu darganfod yno.

Arweiniodd hyn at weithdy yn yr amgueddfa gyda'r prif archaeolegydd, yn edrych yn fanylach ar yr hyn a ddarganfuwyd ar y safle a beth allai hyn ei ddweud wrthym am y ffordd roedd pobl yn byw ar y pryd, ac roedd hyn yn hynod ddiddorol i bawb yn y grŵp.

Mae llawer o gyfleoedd dysgu yn cael eu trafod yn y fforymau a gallaf roi gwybod i'm grwpiau i fel y gallan nhw fanteisio ar y cyfleoedd os ydyn nhw'n dymuno.

Mae Loveday yn llawn gwybodaeth ac yn gyfeillgar tu hwnt, ac yn dda iawn am gysylltu pobl â'i gilydd er budd pawb. Mae wedi bod yn fraint i fod yn rhan o'r fforwm." (Lesley, Ymarferydd Adfer, Hafal)

Cynnal cyrsiau yn Sain Ffagan

Ers agor y cyfleusterau newydd yn Sain Ffagan yn 2017, rydym wedi gweithio'n galed gyda phartneriaid i sefydlu cyfleoedd i sefydliadau eraill ddod â'u cyfleoedd dysgu i'r Amgueddfa. Rydyn ni wedi gweithio gydag Adran Ehangu Mynediad Met Caerdydd, a ddaeth â chyfres o weithdai i'r Amgueddfa yn 2019, er enghraifft, Ysgrifennu Creadigol a Therapi Ategol. Roedd y cyrsiau hyn yn defnyddio'r Amgueddfa a'i chasgliadau i greu ysbrydoliaeth a dylanwadu ar gynnwys y cyrsiau. Mae'r bartneriaeth hon yn galluogi dysgwyr i brofi persbectif unigryw Cymreig ar eu profiad dysgu.

Dyma'r hyn roedd gan dîm Ehangu Mynediad Met Caerdydd i'w ddweud am y bartneriaeth:

“Bu'n bleser o'r mwyaf i gydweithio â Sain Ffagan, ac mae hyn wedi'n galluogi ni i gyfoethogi'r cyrsiau drwy rannu'r adnoddau a'r arbenigedd rhagorol sydd ar gael yn yr Amgueddfa. Mae tiwtoriaid o'r Brifysgol yn gallu gweithio gyda'r staff yn Sain Ffagan i ymgorffori diwylliant Cymru i'w cyrsiau ac mae'r creiriau yn dod â phopeth yn fyw i'r myfyrwyr.

Drwy rannu adnoddau, cyhoeddusrwydd ac arbenigedd, mae'r myfyrwyr yn cael budd ehangach drwy’r bartneriaeth nag y byddai’n bosibl fel arall. Rydyn ni hefyd yn gallu cyrraedd cymuned ehangach ac yn gallu ymgynghori drwy gyfrwng y fforwm dysgu fel bod gennym ddealltwriaeth well o'r hyn y byddai'r gymuned yn dymuno'i ddysgu.

Yn olaf, mae'n wych gallu cynnal cyrsiau mewn adeiladau mor anhygoel a chael cymorth gan yr holl staff sydd bob amser yn broffesiynol, yn gyfeillgar ac yn bwysicaf oll, yn cynnig croeso cynnes." (Jan Jones, Pennaeth Ehangu Mynediad, Met Caerdydd).

Rydyn ni hefyd yn gweithio'n agos â Chymraeg i Oedolion yn Ysgol y Gymraeg ym Mhrifysgol Caerdydd. Rydyn ni wedi cynnal Sadwrn Siarad, diwrnod o weithgareddau Cymraeg, yn ystod yr haf am sawl blwyddyn, ond yn 2019, roedden ni'n gallu cynnig gofod ystafell ddosbarth er mwyn cynnig dosbarthiadau Cymraeg gyda'r nos yn Sain Ffagan. Cynhaliwyd peilot ym mis Ionawr 2019 pan ddechreuodd cwrs Mynediad 1. Yn dilyn llwyddiant hwn, dechreuwyd dau gwrs pellach yn y mis Medi canlynol, ac aeth y dysgwyr o'r cwrs cyntaf ymlaen at gwrs Mynediad 2.

Dyma'r hyn sydd gan dîm Cymraeg i Oedolion yn Ysgol y Gymraeg i'w ddweud am y bartneriaeth:

“Mae Dysgu Cymraeg Caerdydd yn falch iawn o gael y cyfle i gydweithio â Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru. Ffurfiwyd y bartneriaeth drwy Fforwm Addysg Oedolion sy’n cael ei arwain gan Loveday Williams o’r Amgueddfa ac mae’r cyd-weithio rhyngom wedi mynd o nerth i nerth ers hynny. Yn Ionawr 2019, cynhaliwyd cwrs dysgu Cymraeg lefel Mynediad ar gyfer dechreuwyr yn yr Amgueddfa. Mae’r gwaith wedi dwyn ffrwyth ers hynny gan i ni ddarparu tri chwrs ym mis Medi 2019, cwrs dilyniant a dau gwrs lefel Mynediad i ddechreuwyr. Er i ni orfod oedi’r dysgu wyneb yn wyneb ym mis Mawrth eleni, mae’r holl gyrsiau wedi parhau’n rhithiol ac yn parhau ar-lein am 2020-2021. Felly er nad oes modd i ni gynnal dosbarthiadau yn Sain Ffagan ar hyn o bryd, mae’r Fforwm Addysg Oedolion yn ein galluogi ni i barhau i gyd-weithio a chynllunio at y cyfnod nesaf.” (Mari Rowlands, Dysgu Cymraeg Caerdydd)

Edrychwn ymlaen at barhau i weithio gyda phob un o'n partneriaid a sefydlu partneriaethau newydd yn y dyfodol, wrth i ni asesu sut olwg bydd ar ein "normal newydd" a sut y gallwn ni barhau i weithredu a thyfu ein darparu addysg i oedolion.