Rust but not bust

, 3 Hydref 2016

Nothing lasts forever, not even in your favourite museum. The job of the conservator is to preserve the national collection but decay is all around us. Sometimes it feels like being a surgeon on an intensive care unit. Fortunately we do have a lot of science and technology to help us.

I have recently written about how we refurbished a collection store because corrosive gases being emitted from wooden cupboards caused some metal objects to show early signs of decay. In this blog I want to walk you through the science and analysis behind this project.

Iron rusts, every kid knows that. Leave a nail out in the garden and within weeks, days perhaps, you will notice it develops a lovely orange colour; given enough time, some moisture and oxygen it will eventually become flaky, friable and disintegrate. What happens when iron rusts? Iron atoms react with oxygen and water molecules, leading to oxidation of iron. The result are hydrated iron oxides, a small family of minerals commonly called rust.

Rusting iron has long been a bane of humanity. The Forth Bridge has to be repainted over and over again because it didn’t it would rust and collapse into the Firth below. The same is true of our own Menai Suspension Bridge here in Wales. Wales was the place for the invention of a rust-proofing process for household products made of iron. In the late 17th Century, Thomas Allgood of Pontypool developed a coating for iron involving the use of an oil varnish and heat. This process was called ‘japanning’, as a European imitation of Asian lacquerwork. Pontypool Museum has lots of information about these old local industries on its website so please visit there if you would like to know more.

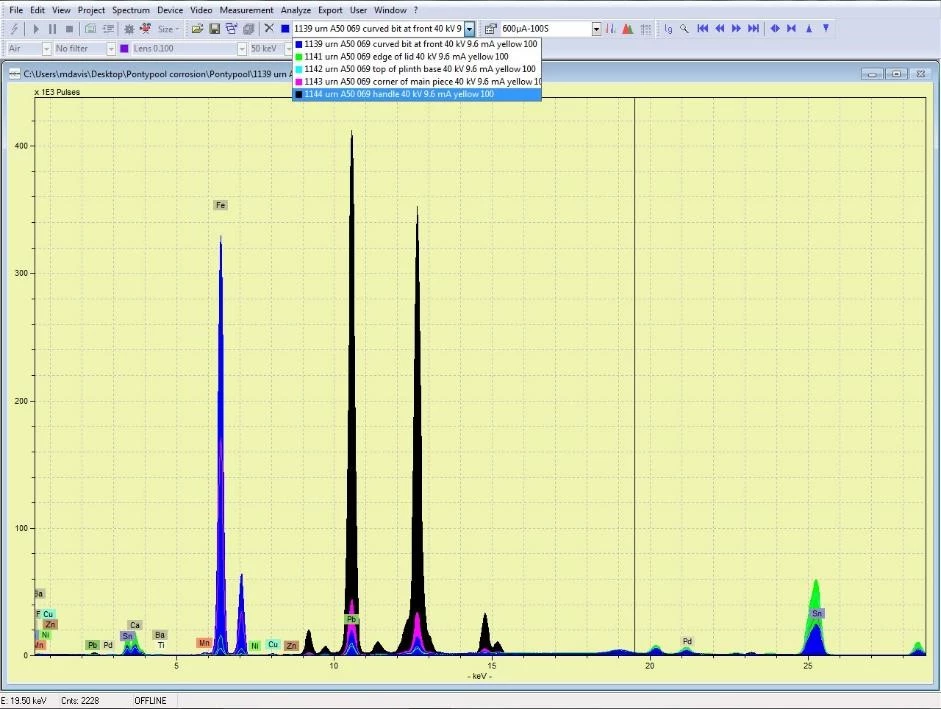

National Museum in Cardiff has a collection of Welsh japanned ware which was largely acquired during the early years of the National Museum. Many of these objects do not consist of iron alone: lead, tin, copper and zinc all feature in varying proportions in different parts of some of the objects. Complicated parts, such as handles and bases, were parts made from softer metals or alloys. We can find out what materials an object is made of using a completely non-invasive technology called X-ray Fluorescence (XRF). XRF directs X-rays towards an object and analyses the X-rays that bounce back. As different elements have their own, unique X-ray fluorescence which the instrument can identify and even use to quantify the elemental composition of objects without having to take a physical sample.

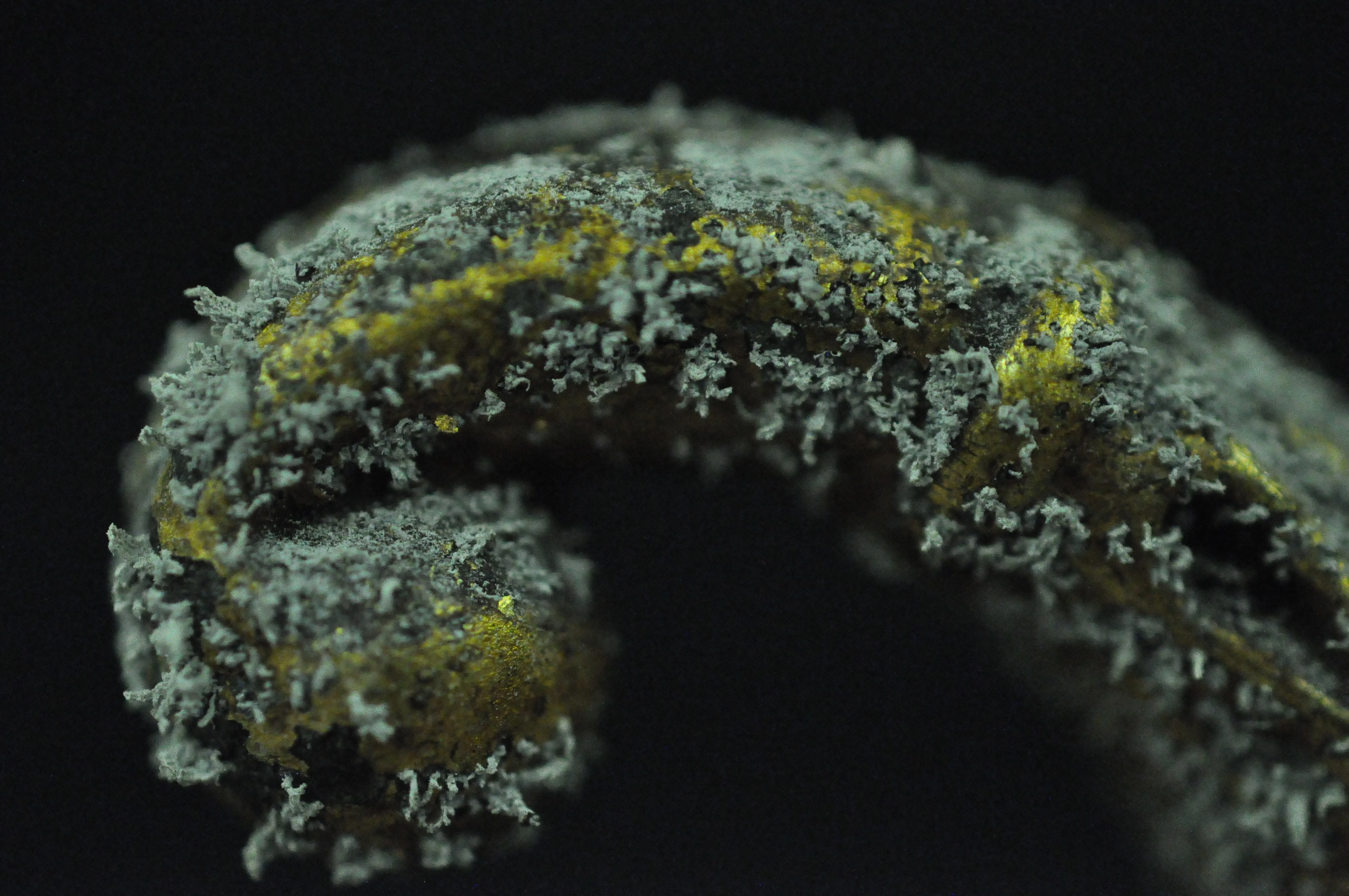

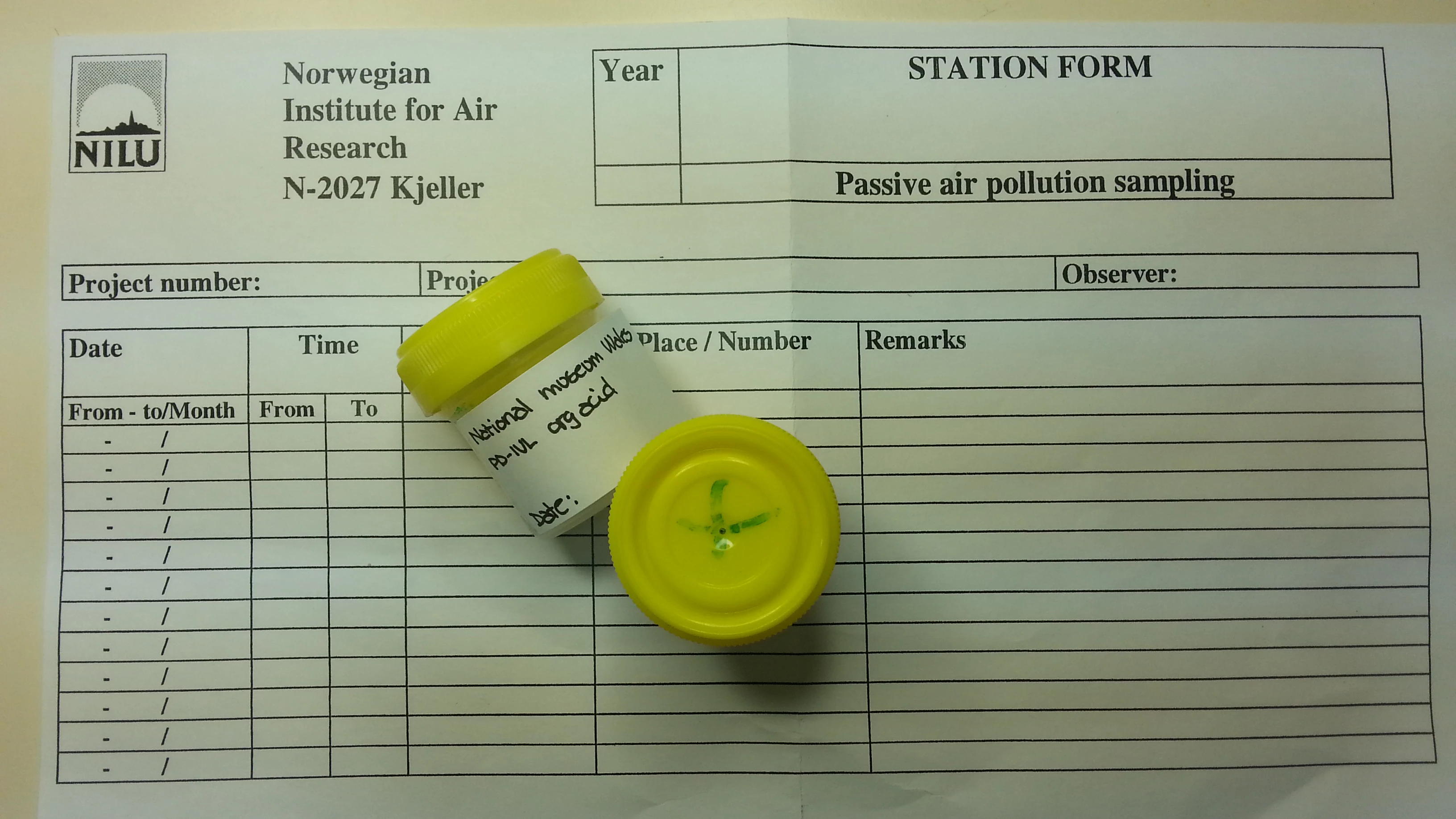

The problem for the museum conservator is that many of these metals, too, corrode under certain circumstances. In the case of the objects which were subject to the previous blog the corrosion of parts with a high lead component was accelerated by the high organic acid concentration within the old storage cupboards. A number of analytical tests exist for identifying and quantifying organic acids in air; we used small discs with an absorbent material that were exposed to the air in the store (both inside and outside of the cabinets) and later analysed in the lab. The results of this test showed that the concentration of acetic acid was 623µg/m3 (250ppb) inside the cabinets and 19µg/m3 (8ppb) in the store, and the concentration of formic acid 304µg/m3 (159ppb) inside the cabinets and 10µg/m3 (5ppb) in the store.

We know that both acetic and formic acids are emitted by wood, and both acids can react with various metals to produce, in some cases, some impressive corrosion products. Clearly, the concentrations of both acids were higher inside the storage furniture than in the store itself, giving us a massive clue that the problem was caused by the cabinets and not air pollution entering the store through the air conditioning system. The fresh air supply into the store, on the other hand, kept the concentration of pollutants low in the store itself.

Corrosion and decay comes in many forms, and we also use other technologies to help us identify corrosion products. Of these more in a future blog. In the meantime we are continuing to eliminate the sources of corrosive substances from the museum to help preserve the national collection.

Find out more about care of collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.