A Day in the Life of a Natural History Curator

, 11 Mai 2020

A Day in the Life of a Natural History Curator

My name is Jennifer Gallichan and I am one of the natural history curators at National Museum Cardiff. I care for the Mollusc (i.e. snails, slugs, mussels, and octopus) and Vertebrate (things with backbones) collections. Just like everybody else, museum curators are adapting to working from home. But what did we use to do on a 'normal' day, before the days of lockdown?

Caring for the National Collections

Most of our specimens are not on display. Amgueddfa Cymru holds 3.5 million natural history specimens and the majority are held behind the scenes in stores. Caring for the collections is an important part of our role as curators. We have to meticulously catalogue the specimens to ensure that all of the specimens are accounted for. As you can imagine, finding one object amongst 3.5 million could take a while.

We spend a lot of time working with you, our fantastic visitors. Much of our time is spent answering the thousands of enquiries we receive every year from families, school children, amateur scientists, academics of all kinds, journalists and many more. We also host open days and national events throughout the year which are another great opportunity to share the collections. Many of us are STEM (Science, Technology Engineering & Mathematics) ambassadors, so an important part of our role inspiring and engaging the next generation of scientists.

Our museums are crammed full of fascinating objects and interesting projects to inspire and enjoy. We spend a lot of time with our excellent volunteers, helping them to catalogue and conserve the collections, guiding them through the often intricate and tricky jobs that it has taken us decades to perfect.

Museums across the world are connected by a huge network of curators. We oversee loans of specimens to all parts of the globe so that we can share and learn from each other’s collections. We have to be ready to deal with all manner of tricky scenarios such as organising safe transport of a scientifically valuable shell, or packing up and transporting a full sized Bison for exhibition.

Despite the fact that a large part of the collections are behind the scenes, they are open to visitors. Researchers from across the globe come to access our fantastic collections to help with their studies. We also host tours of the collections on request.

Despite having millions of specimens, museum collections are not static and continue to grow every year. Be it an old egg collection found in an attic, or a prize sawfish bill that has been in the family for generations, it’s an important part of a curator’s job to inspect and assess each and every object that we are offered. Is it a scientifically important collection or rare? Has it been collected legally? Do we know where and when it was collected? Is it in a good condition? Do we have the space?

A fun part of the job is working with our brilliant Exhibitions department to develop and install new exhibitions. We want museums to be exciting and inspiring places for everyone so we spend a lot of time making sure that the information and specimens we exhibit are fun, engaging, inspiring and thought provoking.

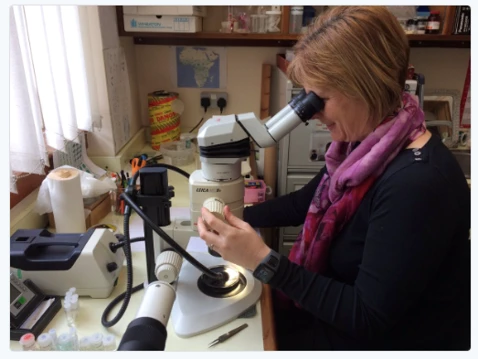

Last but definitely not least, when we aren’t doing all of the above, we are doing actual science. Museums are places of learning for visitors and staff alike. Many of us are experts in our field and undertake internationally-recognised research. This research might find us observing or collecting specimens out in the field, sorting and identifying back in the lab, describing new species or researching the millions of specimens already in the collections.

Despite lockdown, we are working hard to keep the collections accessible. We’re answering queries, engaging with people online, writing research papers and chipping away at collection jobs from home. And like all of you, we are very much looking forward to when the museum opens its doors once again.

If you want to find out more about the things we get up to in the museum, why not check us out on Twitter or follow our blog? You can also find out more about all of the members of the Natural Sciences department here.

sylw - (2)

Hi Adam

Thanks for your message. There are a variety of ways that animals come into the collections at the Museum. Many of them were collected in the 1800s–1900s, others are more recently collected or donated. Many of the donations to the museum are from specialists and enthusiasts that built up collections of their own. All new specimens must be sourced with appropriate licences, and from proper sources, and you must have a very good reason to collect them.

Lots of specimens are on display in the galleries to help our visitors learn more about the natural world. Others are kept in our stores behind the scenes for research by staff and visitors. Museums are also important storehouses for biodiversity – holding a record of the natural world over time. For example, we hold specimens of 10 extinct species of vertebrate, including the Dodo and Tasmanian Tiger. Specimens in the collections help us all to better understand our environment and, in some cases, help preserve existing species or ecosystems.

How we study the specimens differs depending on the type of animal it is, and what we want to know. So, for example we might take a sample of skin or fur for analysis to tell us more about the environment it lived in. We might also study the animal’s skeleton or teeth to learn about how it moved, or what it ate. If the specimen is smaller, or we want to look at the microstructure of something, we use a microscope to look at it up close. We also have a DNA lab at the museum so we can learn more about its genetic makeup, such as how closely it is related to another species. Lots of animals are very small and so can only be studied under microscope.

You can learn more about the collections by visiting our web pages and by reading more of our blogs tagged with Natural History.

With best wishes

Jen Gallichan (Curator of Vertebrates)