: Amgueddfeydd, Arddangosfeydd a Digwyddiadau

The Museum's gone Quentin Blake and Roald Dahl Crazy!

, 5 Awst 2016

Since the launch of the Quentin Blake exhibition our inbox has been filling up, and the phone hasn’t stopped with fellow Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake superfans wanting to know more about what's going on. Everyone wants to get involved! So I thought I’d share a little bit of what’s been happening so far.

The Exhibition

People have been coming along to draw in the gallery and already our wall is bursting with wonderful drawings.

Want to join in? https://museum.wales/cardiff/whatson/8916/Quentin-Blake-Inside-Stories/

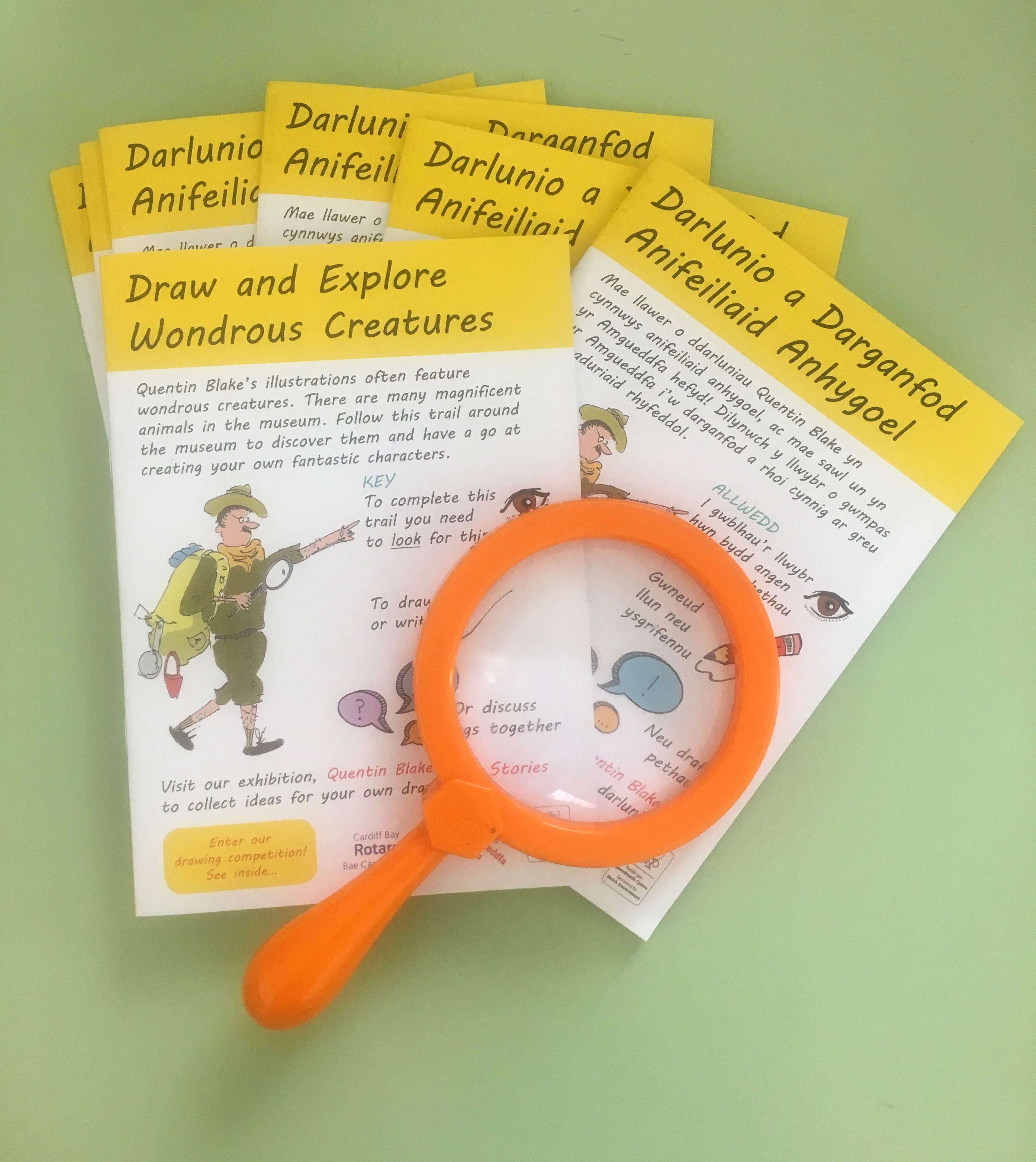

Activity Booklet

Our activity booklets have been flying out and the competition entries have been coming in thick and fast!

To draw your way around the museum and take part in the competition, just pop in to the Clore Discovery centre to get your very own booklet https://museum.wales/cardiff/clore/

Family Workshop

Families have been making some really nice little storybooks of their very own.

Teachers

We have a teacher's pack in both Welsh and English that will help you explore the exhibition with your class - https://museum.wales/media/38707/QB-FINAL.pdf

Cymraeg - https://amgueddfa.cymru/media/38708/QB-FINAL-cy.pdf

If you would like to bring your class to the museum all the information you need about booking is available at - https://museum.wales/cardiff/learning/booking_information/

The Welsh dinosaur comes back to life

, 21 Gorffennaf 2016

When you turn a corner in our Evolution of Wales galleries don’t be surprised if you find Dracoraptor hanigani, the new Welsh dinosaur, peering down on you from its perch on a rock.

The skeleton of this small meat eating dinosaur, currently on display in the Main Hall at National Museum Cardiff, has fascinated the public, but palaeontologists at Amgueddfa Cymru wanted a life-like model of the animal to really show how it looked when it was alive 200 million years ago in the Jurassic.

Bob Nicholls, a Bristol–based palaeo-artist, was commissioned to undertake this task. First Bob had to undertake extensive research to enable him reconstruct the dinosaur. He examined the bones and drew an anatomically accurate skeleton, comparing it to other species. He then added the soft tissue and considered how it would have lived before making an anatomically accurate model using steel, polystyrene, and clay. This was then moulded and a cast made of fibreglass and resin.

It was important to make sure that the reconstruction was as scientifically accurate as possible. Palaeontologists think that the body might have been covered in a feathery down, and possibly with quills along its back and Bob carefully applied feathers to the surface of the model and long quill-like feathers on the back, tail and neck. This was a meticulous process because they all had to be attached in a way that looked natural.

The project took over three months of painstaking work and after it was completed Bob said “There is no greater honour for a palaeo-artist than to be the first to show the world what a long extinct animal looked like”.

The result is incredible - you can imagine Dracoraptor jumping down into the gallery and running around.

Glamming up the worms!

, 8 Gorffennaf 2016

Our exciting, family-friendly exhibition ‘Wriggle’ has recently opened delving into the wonderful world of worms. Producing this exhibition has taken many months of planning, hard work and some excellent teamwork.

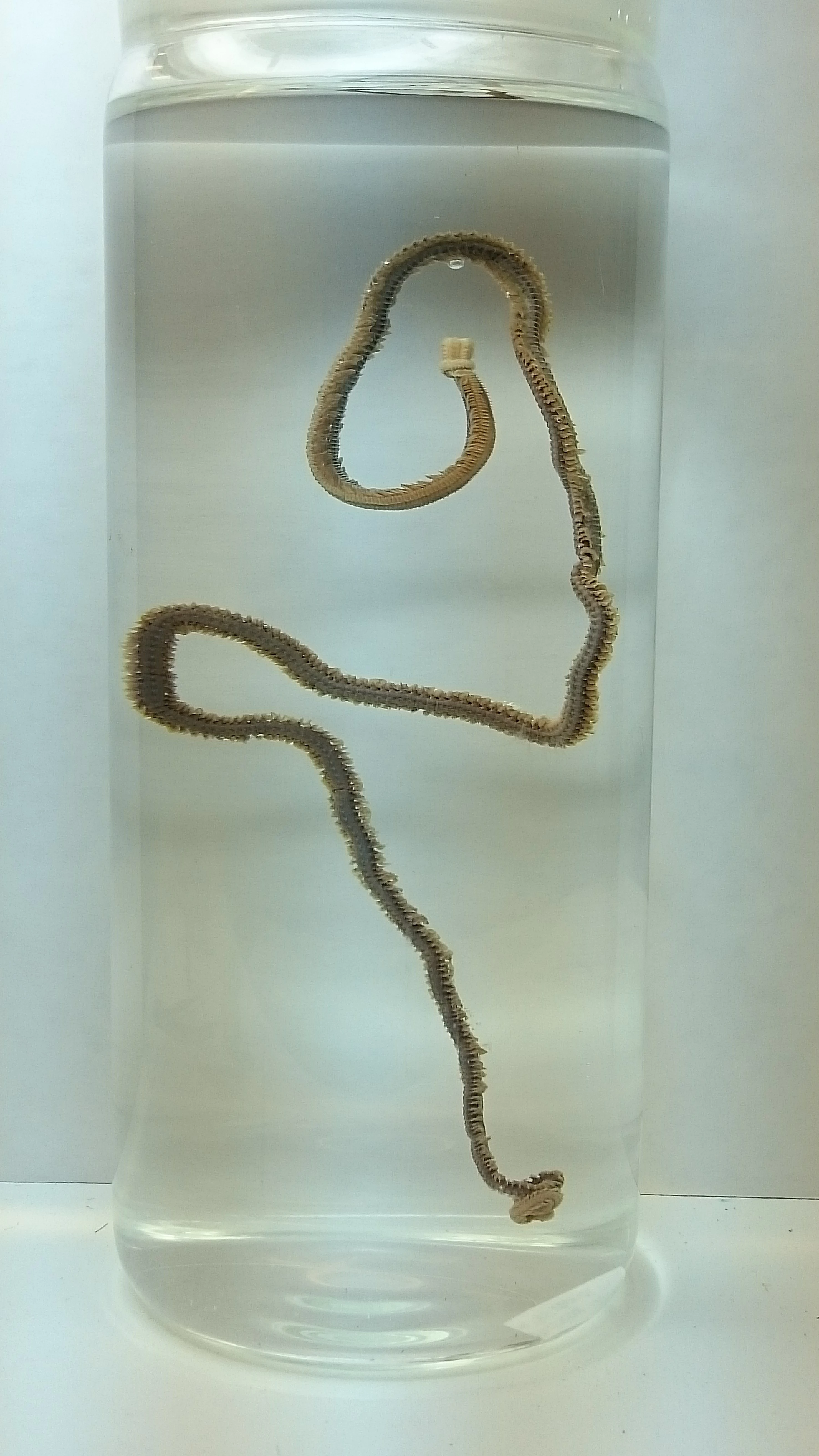

The natural science conservators have been very much part of that team, and in the run up to the opening we were very busy working on numerous specimens and creations. My talented colleague Annette focused on creating the beautiful mini dioramas and other displays in the wonderful ‘wriggloo’ center piece. However my role was to work on ‘glamming’ up the worms from our fluid preserved collections!

Fluid preservation, or ‘pickling’ as it is affectionately called, is an important means of preserving many of our specimens. The fluid stops decay and helps preserve the whole 3D form of an animal or plant specimen. Many different fluids can be used but the familiar and commonly used ones are chemicals like ‘formalin’ or alcohol.

Unfortunately there can be many problems to using fluid preserved specimens in display. Whilst the 3D shape is kept, colour cannot be properly preserved. Also many of the chemicals used are potentially toxic and need to be avoided in a public environment. Thus the challenge is to make that brownish, stringy shape in the bottom of a jar safe to display and to look like the worm it is!

Working closely with our worm curators we first established where the specimen was going to be displayed in the exhibition. It was then a case of working through the selected specimens for use in the exhibition and deciding how best they could be displayed.

The overall aim was to make the worms look smart! So we used our best museum jars of beautifully craft borosilicate glass made by a British company called Dixon glass. We also have a stock of rectangular jars called ‘battery’ jars. These are very difficult to obtain but make wonderful display jars. Fluids were changed where required and a number of techniques used to display the worm clearly in the jar so that the visitor can see it at its best.

The result is a rich mix of real specimens embedded in a family friendly and interactive exhibition - it is always very pleasing to be able to display a part of the science specimens in a gallery situation.

If you visit the exhibition then please do take a close look at the diversity of all these worms, and we very much hope you enjoy the visit.

All hail the dragon

, 7 Gorffennaf 2016

During the past two weeks our Geology galleries were closed for essential maintenance. Now they are open to the public again, much to the delight of anyone looking after dinosaur-mad 6-year olds, who, quite rightly, have been disappointed by the temporary withdrawal of some of National Museum Cardiff’s most popular displays.

So in you come for a peek of all those refreshed displays. But what’s that? Seemingly nothing has changed?? Everything still looks as it did before the ‘major refurbishment’ – so what was so major about it?

The idea of undertaking maintenance was not to change the displays – apparently our visitors are happy with the way they are – but to update technology and fix things that were broken. This is why you have to look closely to spot what we have been so busy doing. Very busy in fact; including the planning phase, which took several months, we had at least 23 people working on the gallery. It was very busy every day, with staff and contractors working around each other, from the dinosaur foot prints pavement all the way up to the ceiling (which is 12m high in this gallery).

What you won’t notice is that the fire beams were replaced to alert us early and reliably in the event of a fire. You’ll have to look closely to spot the new lights: the spot lights underneath the ceiling are now all converted to LED. You may find that the image quality of the display screens is a million times better than it was before. What you certainly should notice is that the displays are much cleaner. We also repaired damage to displays. As the saying goes: if you touch - we need to touch up. The paint work, that is. And if anyone happens to walk into a display case the specimens inside move sometimes. If we don’t spot this early enough, they can topple off their shelf and break. We used the opportunity last week to put them all back in their place, hence our plea to you: this is now not a race to see how quickly they can be knocked off their perch again, so absolutely no prize for anyone who thinks they can dislodge the displays. Our specimens – which, actually, belong not to the museum but to the Welsh public – are fragile and repairing them costs tax payers’ money, which we do our best not to waste.

There is one thing that is entirely new to the gallery, something which will be obvious immediately to said 6-year old dinosaur enthusiast (and those of any other age, too): the new Welsh dinosaur now has a permanent home as part of our dinosaur display. A life-sized artist’s impression, feathers and colours and all, is now peeking from the early Jurassic back to its Triassic cousins. It is truly magnificent and inspiring, and actually one of the first models to represent the latest research that these kinds of dinosaurs were clad in feathers. The enthusiast in myself wants to add pathos to this announcement, which is difficult to express in a blog. Hence I’ll stop myself right here and simply invite you to come and see it.

Oh, one more thing. While working in the displays in the past two weeks we found countless sweet wrappers, discarded chewing gums and bits of sandwiches and apples in various hidden corners. These kinds of things encourage pests which we don’t want in the museum any more than you would want them in your house. We have the restaurant, café and schools sandwich room where you are welcome to eat, and there are bins in the Main Hall before you enter the galleries. We would be immensely grateful if you didn’t take any food into the galleries.

Find out more about care of collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.

cofnodion diweddar

Goleuo’r Ffordd – Pennod Nesaf Neuadd Weston

Gweithdai Rhithwir Bylbiau'r Gwanwyn i Ysgolion

Cynhesrwydd y Gaeaf yn Amgueddfa Wlân Cymru: Lapiwch Eich Hun yn Hud y Gwlân

Blwyddyn eithriadol! Blwyddyn ers cau drysau'r Amgueddfa Lechi dros-dro ar gyfer ailddatblygu!

categorïau

- Pob cofnod

- Addysg

- Ailddatblygu Llechi

- Amgueddfeydd, Arddangosfeydd a Digwyddiadau

- Blog y Siop

- Casgliadau ac Ymchwil

- Casglu Covid

- Crefftwyr Amgueddfa Wlân Cymru

- Cyffredinol

- Holiaduron y gorffennol a’r presennol

- Iechyd, Lles ag Amgueddfa Cymru

- Lleisiau’r Amgueddfa

- Rhyfel Byd Cyntaf

- Streic! 84-85 Strike!

- Ymgysylltu â'r Gymuned