Museums are outgoing institutions. Our doors are open to anyone, regardless of age, level of ability, ethnicity, and so on. We are happy to welcome everyone and will do our best to accommodate people’s needs and interests. Many museums are free because we do not want low income to be a barrier for visiting. AC-NMW’s Conservation Department has recently stepped up its outreach programme. We organise regular Open Days (the next one is on 25th October), talks, behind-the-scenes tours, schools activities etc – preservation of the museum’s objects is an important part of what the museum does and quite rightly forms part of the museum’s public offer. So much for museums.

Now for the visitors. Why do people visit museums? Because they have travelled here and are trying to get a sense of place. Because they want to spend some quality time with friends/family. Because they have a specific interest. There are many reasons, most of which indicate that visiting museums is a leisure activity that reflects what people are interested in and how they like to spend their spare time, just like reading, cycling or watching box sets on TV. Jehra Patrick summarised in her blog some of the motivational identities of museum visitors compiled by John H. Falk. She also suggested that to get people in the doors, museums should stop telling them why they should come and start asking them why they do.

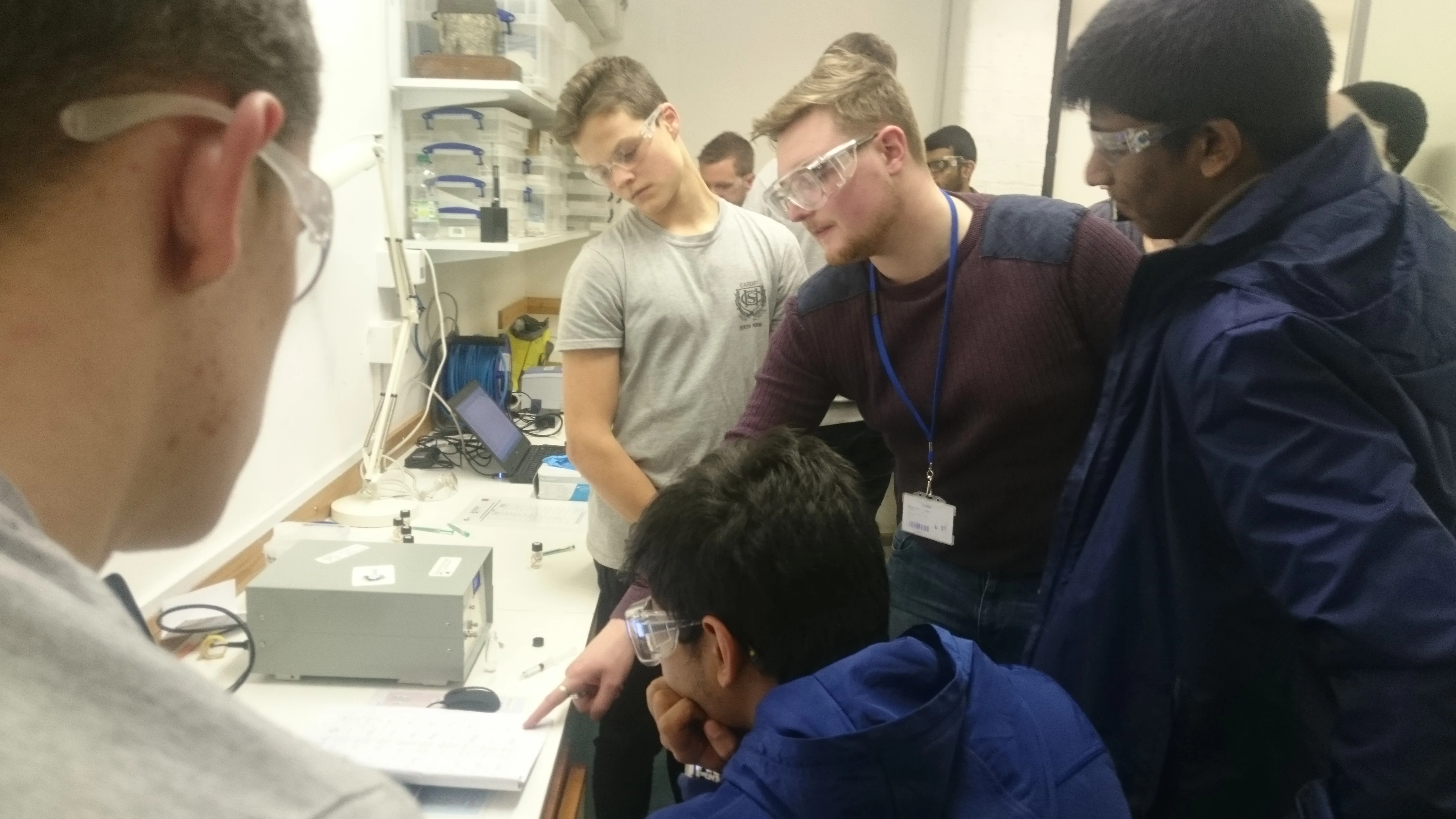

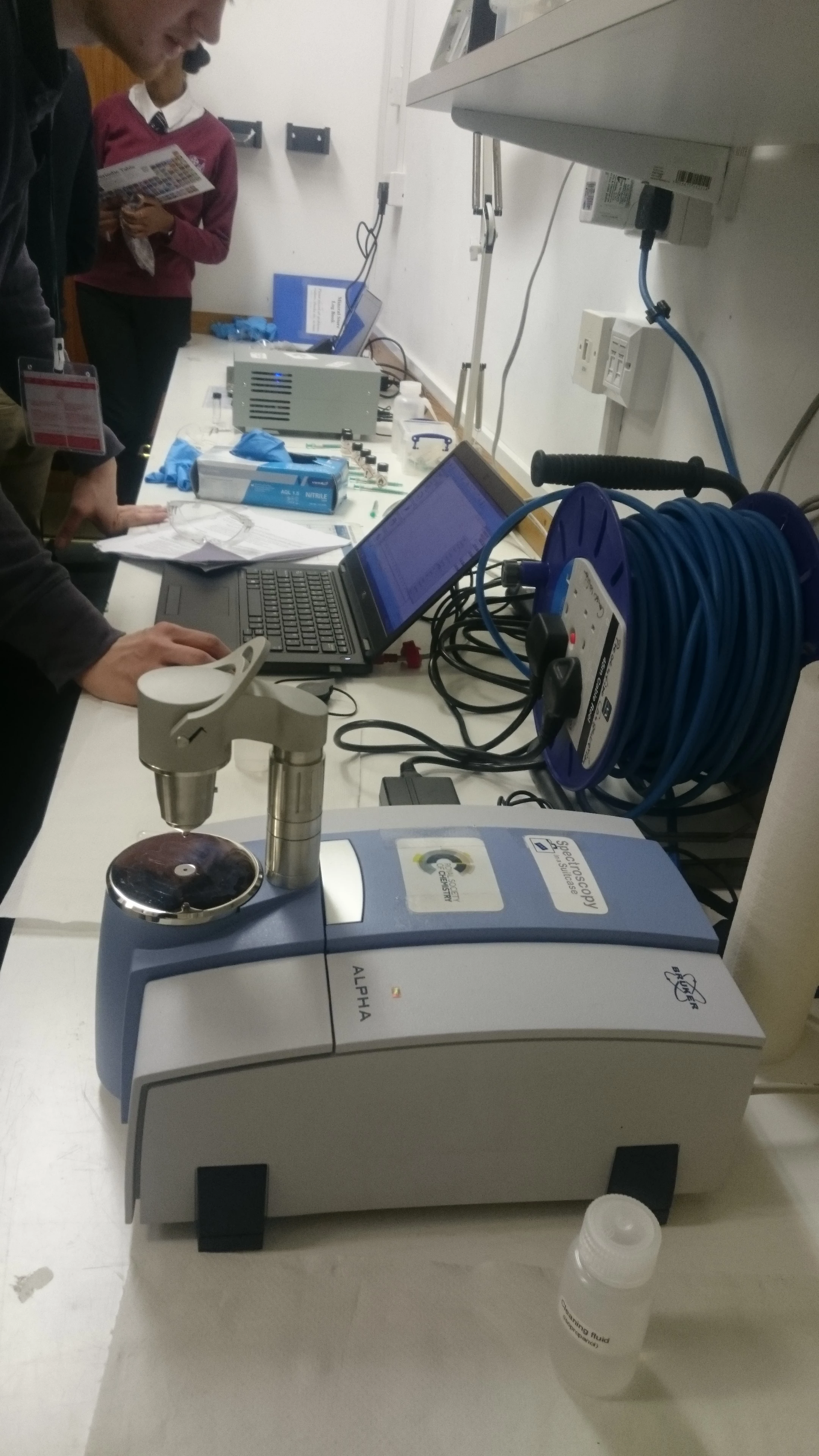

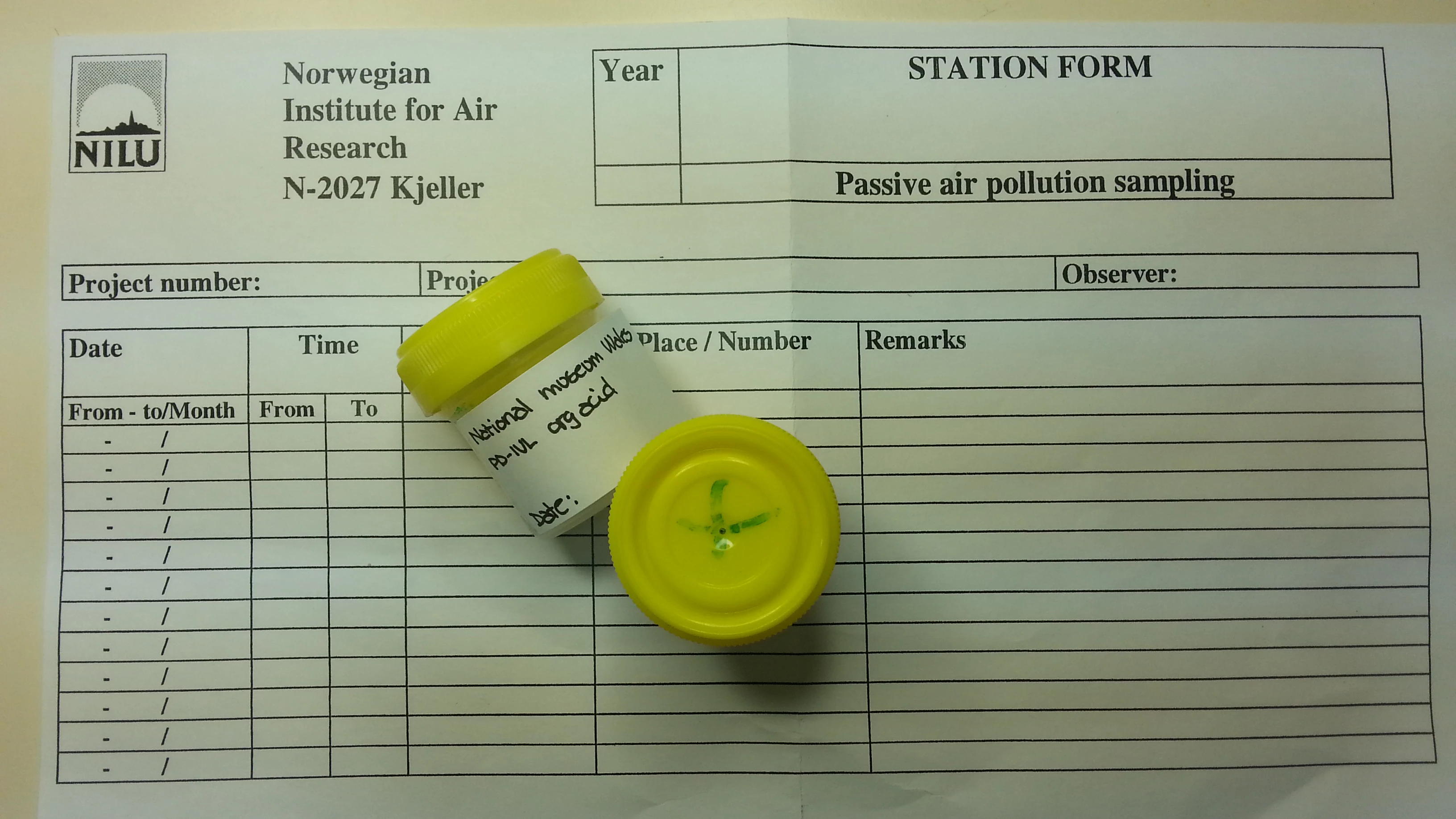

Last year we asked visitors whether they would like conservators to be more visible in public spaces. The feedback was a resounding and emphatic ‘YES!’ by 90% of our visitors. We heard the shout and started scheduling more of our regular maintenance work during public opening hours both at St Fagans and in the city centre. Again we checked with the visitors and, low and behold, they said they would like to see conservation in action even more often. Visitors are insatiable, one might conclude. Or are we really that good? Either way, it was all good news, the new way of working was a success, we congratulated ourselves, lots of shoulder padding going on etc.

Now a dear friend asked recently: ‘do visitors like to talk to museum staff about Conservation, or do they just like to talk to staff?’ Jaw drops. Had we not asked visitors whether they would like to speak to conservators? And had they not told us that they did? Well, yeah – but what we didn’t ask was whether it mattered that they spoke to conservators. Or anyone else.

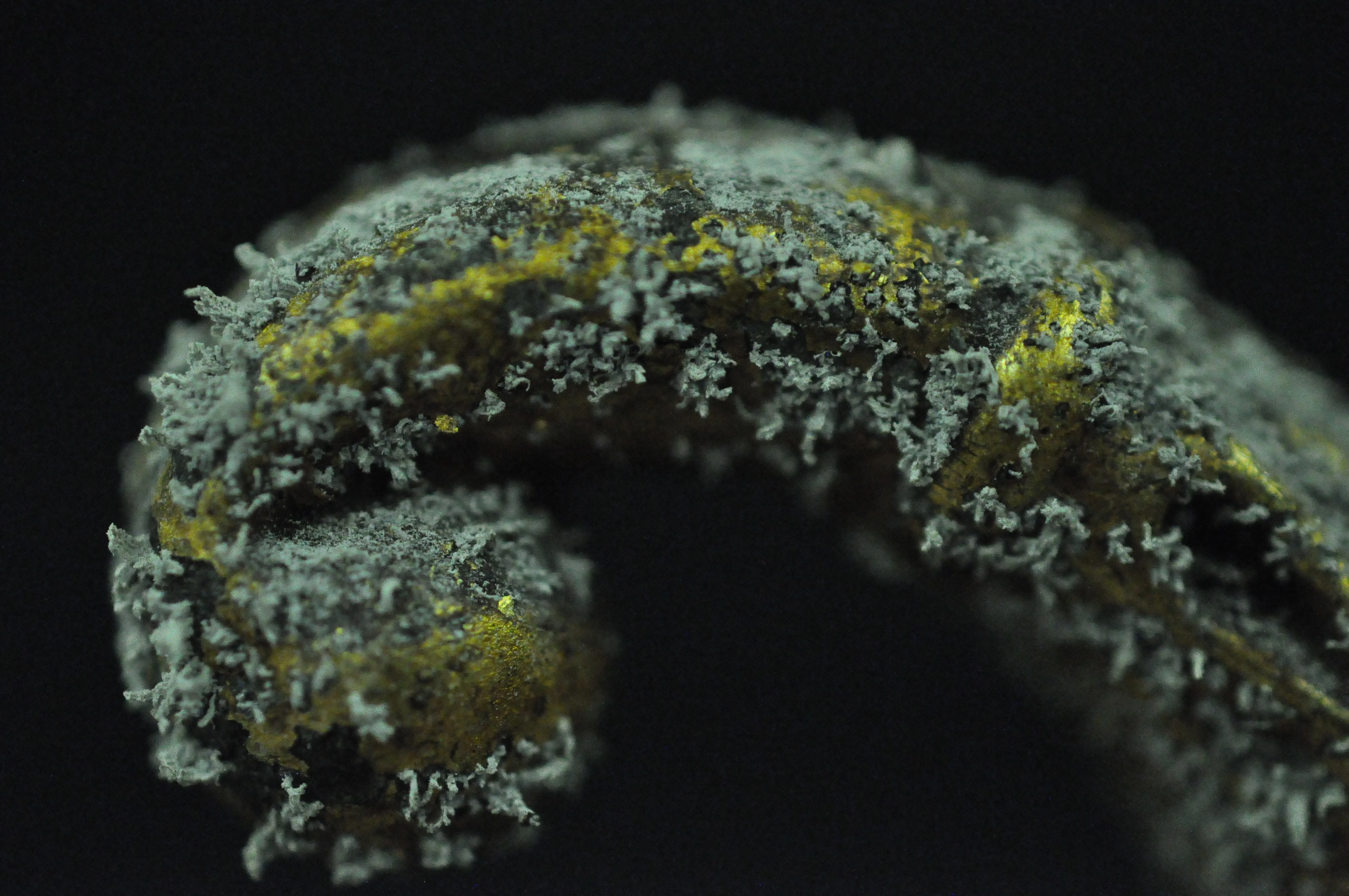

It is certainly clear from experience (I am now straying from hard data into anecdotal evidence) that many museums visitors like to talk. When we work in the galleries or historic houses there are endless opportunities for chatting. We, as staff and volunteers, make it as obvious as possible that we are approachable and happy to talk. Many visitors use the opportunity to do just that: ask questions about our work, about the objects on display, or tell us about a moth infestation they once had in a carpet. The latter does not tend to happen randomly – pest management is one aspect of our work.

However, there is certainly a difference between being a member of museum staff (visitor perception) and being a highly skilled individual with years of experience who is fully subscribed to the museum’s policy of inclusivity, enthusiastically raring to inform visitors about the museum’s efforts in heritage preservation (conservator perception). It is interesting to note that, when working in the galleries, conservation is not the only thing we talk about. We also find ourselves giving directions, answering questions about objects on display, telling people about other cultural venues in South Wales. And – for reasons of liability – avoiding giving advice on moth infestations in domestic carpets.

Does it need a conservator to answer general enquiries? Of course not, and the museum already has additional staff for just that sort of thing. Should a conservator therefore refuse to answer such questions? Again, of course they should not – courtesy and politeness alone should be reason enough to attempt to answer any question.

Visitors cannot be expected to distinguish between different members of museum staff or volunteers. I, as a conservator, have to be aware of this and be prepared to answer any question asked of me as best I can to create experiences that fulfil visitor needs. It is also clear that visitors have expectations of their museum experience that often differ from what staff believe the offer is. The route to success for me, as member of staff, is therefore to be flexible and acknowledge the visitor’s diverse interests and needs. And to ask the right questions.

Find out more about care of collections and Preventive Conservation at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.