Accidents happen: we drop our favourite coffee cup in the kitchen and it shatters into a million pieces; parking the car, we misjudge the distance to that bollard and, oops, scratch the car; the faulty television overheats and catches fire. We usually try to protect ourselves against such accidents by assessing the risk, and mitigate against risk to help us avoid accidents. We install smoke detectors, fire extinguishers and emergency stairs to help us get out of a burning building should the worst happen.

Our immediate thought in the event of a disaster is, quite rightly, the preservation of life. But objects that mean something to us are often a victim of disasters, too. This may be the family photographs getting lost in a house fire. Or it could be an entire historic building, which is important to the local or even national history. The very recent fire at Clandon Park House in April 2015 illustrates how quickly an important part of British social and parliamentary history can be destroyed (the Onslow family, whose estates this was, provided three speakers to the House of Commons over the centuries).

What if heritage is destroyed not by accident, but entirely purposefully? In 2013, a construction company in Belize destroyed a Maya pyramid to turn it into gravel for road fill. The pyramid was 2,300 year old – millennia of heritage, memory and civilisation were destroyed, incredibly, because the ancient structure provided a cheap and easy source of building material.

At other times, heritage – monuments, buildings, statues, or even individual objects – are the target of anger. In post-communist Eastern Europe, statues of Stalin or Lenin are being removed as symbols of power of a by-gone era. Palmyra, the prosperous Assyrian city in today’s Syria, has temples 2,200 years old, was first destroyed by the Romans in 273 AD, by the Timurids in 1400, and is now threatened once again with becoming a casualty of war and ideologies.

Whether you agree with the symbols and ideologies of the people who came before you, our own being is born from previous historic events. Our music, stories, architecture, even our state of government would be nothing without the histories that led up to them. To make sense of our modern world we need to remember – remember positive events for the good they are, and negative events so we can avoid dark hours of history repeating themselves. Ultimately, the past informs our present.

In this project, funded by Cardiff University Engagement Seed Funding, we explore the effect of armed conflict on stone surfaces, emergency planning and heritage salvage, strategies for post-conflict remediation, and construction of memories of WWI or post-communist Eastern Europe.

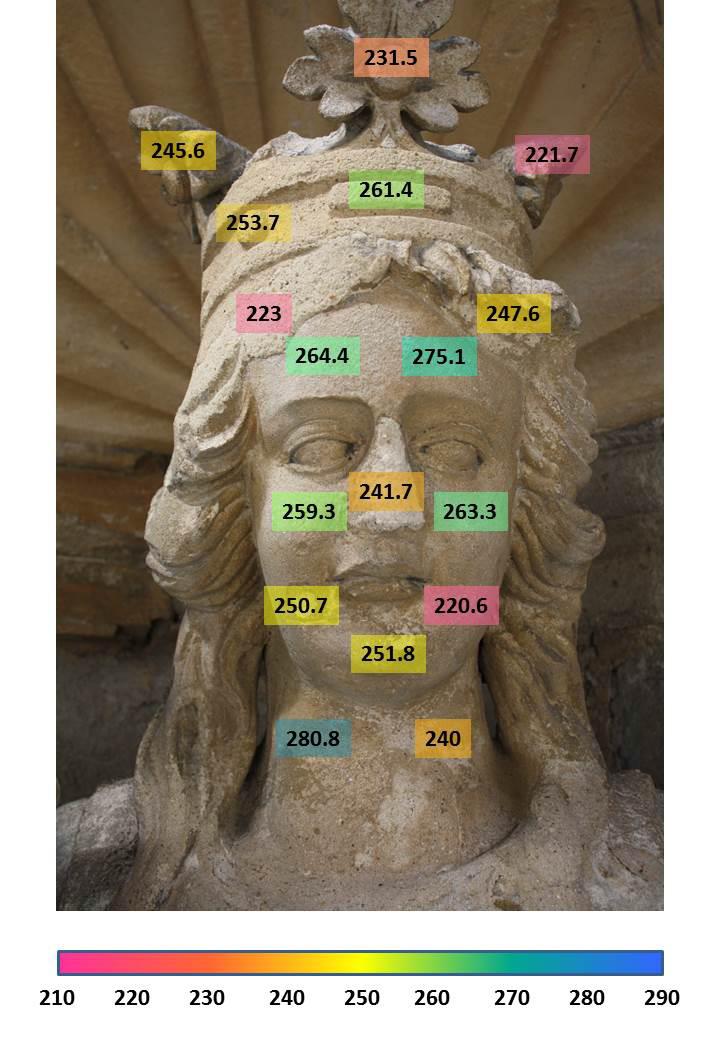

Dr Lisa Mol (Early Career Lecturer, Cardiff University, School of Earth and Ocean Sciences) works on the impact of armed warfare on stone surfaces, which links to heritage conservation and long-term strategies for post-conflict remediation. Lisa asks people to shoot with guns at pieces of building stone to study what happens on impact.

Building on his recently published monograph on the construction of memory of the First World War, and on sites of memory in Eastern Europe, Dr Toby Thacker (Senior Lecturer in Modern European History, Cardiff University, School of History, Archaeology and Religion) will cover the contested role of damaged historical sites in the construction of memory.

Dr Christian Baars (Senior Preventive Conservator, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales) is a member of the Welsh Government’s Emergency Planning Network Wales; he ensures the long-term preservation of museum collections, has experience working with the emergency services and will highlight the importance of preserving heritage for future generations while addressing the issues of looting and illicit trade in cultural objects.

If you are interested in this subject please follow our blog and come along to one of our events at National Museum Cardiff this summer.