Clapio Wyau

, 31 Mawrth 2020

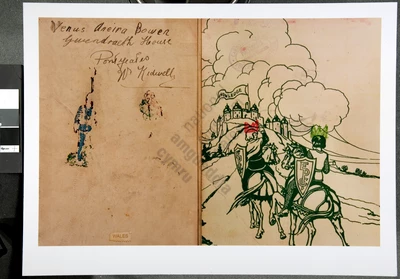

Teclynnau Pren

Mae’n siwr y gallwch restri llawer o’r delweddau sydd o’n cwmpas mewn siopau ac yn y cyfryngau yn ystod adeg y Pasg: wyau siocled lliwgar, cywion a chwningod bach fflwfflyd, y lili wen a theisennau simnel i enwi rhai ohonynt.

Ond tybed a ydych chi’n gwybod beth yw’r ddau declyn yn y lluniau ar y dde?

Arferion y Pasg

Yr wythnos hon bûm yn gwrando ar recordiadau yn yr Archif Sain yn ymwneud ag arferion y Pasg. Ceir sôn am ystod eang o draddodiadau: eisteddfota; “creu gwely Crist”; canu carol Basg; torri gwallt a thacluso’r barf ar ddydd Iau Cablyd er mwyn edrych yn daclus dros y Pasg; bwyta pysgod, hongian bwnen a cherdded i’r eglwys yn droednoeth ar ddydd Gwener y Groglith; yfed diod o ddŵr ffynnon a siwgr brown ar y Sadwrn cyn y Pasg; dringo i ben mynydd i weld yr haul yn “dawnsio” gyda’r wawr a gwisgo dillad newydd ar Sul y Pasg; chwarae gêm o gnapan ar Sul y Pasg Bach (sef y dydd Sul wedi’r Pasg).

Clapio Wyau

Ond y traddodiad a dynnodd fy sylw fwyaf oedd yr arfer ar Ynys Môn o fynd i glapio wyau. Byddai mynd i glapio (neu glepio) cyn y Pasg yn arfer poblogaidd gan blant yr ynys flynyddoedd yn ôl, a dyna yw’r ddau declyn y gellir eu gweld ar y dde: clapwyr pren.

Yn ôl Elen Parry a anwyd yn y Gaerwen yn 1895 ac a recordiwyd gan yr Amgueddfa yn 1965:

Fydda ni fel rheol yn câl awr neu ddwy dudwch o’r ysgol, ella rhyw ddwrnod neu ddau cyn cau’r ysgol er mwyn cael mynd i glapio cyn y Pasg. Fydda chi bron a neud o ar hyd yr wsnos, ond odd na un dwrnod arbennig yn yr ysgol bydda chi’n câl rhyw awr neu ddwy i fynd i glapio. Bydda bron pawb yn mynd i glapio. A wedyn bydda’ch tad wedi gwneud beth fydda ni’n galw yn glapar. A beth odd hwnnw? Pishyn o bren a rhyw ddau bishyn bach bob ochor o bren wedyn, a hwnnw’n clapio, a dyna beth odd clapar.

Byddai’r plant yn mynd o amgylch y ffermydd lleol (neu unrhyw dyddyn lle cedwid ieir) yn curo ar ddrysau, yn ysgwyd y clapwyr ac yn adrodd rhigwm bach tebyg i hwn:

Clap, clap, os gwelwch chi’n dda ga’i wŷ

Geneth fychan (neu fachgen bychan) ar y plwy’

A dyma fersiwn arall o’r pennill gan Huw D. Jones o’r Gaerwen:

Clep, Clep dau wŷ

Bachgen bach ar y plwy’

Byddai’r drws yn cael ei agor a’r hwn y tu mewn i’r tŷ yn gofyn “A phlant bach pwy ’dach chi?” Ar ôl cael ateb, byddai perchennog y tŷ yn rhoi wŷ yr un i’r plant. Yn ôl Elen Parry:

Fe fydda gyda chi innau pisar bach, fel can bach, ne fasgiad a gwellt ne laswellt at waelod y fasgiad. Ac wedyn dyna wŷ bob un i bawb. Wel erbyn diwadd yr amsar fydda gyda chi ella fasgedad o wyau.

Fel arfer, byddai trigolion y tŷ yn adnabod y plant ac os byddai chwaer neu frawd ar goll, byddid yn rhoi wŷ i’r rhai absennol yn un o’r basgeidiau. Dyma ddywedodd Mary Davies, o Fodorgan a anwyd yn 1894 ac a recordiwyd gan yr Amgueddfa yn 1974:

A wedyn, os bydda teulu’r tŷ yn gwbod am y plant bach ’ma, faint fydda ’na, a rheini ddim yno i gyd, fydda nhw'n rhoed wyau ar gyfer rheini hefyd iddyn nhw.

Wyau ar y Dresel

Ar ôl cyrraedd adref byddai’r plant yn rhoi’r wyau i’w mam a hithau yn eu rhoi ar y dresel gydag wyau’r plentyn hynaf ar y silff uchaf, wyau’r ail blentyn ar yr ail silff ac yn y blaen.

Gellid casglu cryn dipyn o wyau gyda digon o egni ac ymroddiad. Yn ôl Joseph Hughes a anwyd ym Miwmaris yn 1880 ac a recordiwyd gan yr Amgueddfa yn 1959:

Bydda amball un wedi bod dipyn yn haerllug a wedi bod wrthi’n o galad ar hyd yr wythnos. Fydda ganddo fo chwech ugian. Dwi’n cofio gofyn i frawd fy ngwraig, “Fuost ti’n clapio Wil?”, “Wel do”, medda fo. “Faint o hwyl ges ti?”, “O ches i mond cant a hannar”.

Math o Gardota?

Er bod pawb fel arfer yn rhoi wyau i’r plant, mae’n debyg y byddai rhai yn gwrthod ac yn ateb y drws gan ddweud “Mae’r ieir yn gori” neu “Dydy’r gath ddim wedi dodwy eto”. Byddai rhai rhieni hefyd yn gyndyn i’w plant fynd i glapio gan eu bod yn gweld yr arfer fel math o gardota. Dyma ddywedodd un siaradwr:

Fydda nhad fyth yn fodlon i ni fynd achos oedd pawb yn gwybod pwy oedd nhad. Wel fydda nhad byth yn licio y byddan ni wedi bod yn y drws yn begio, ond mynd fydda ni.

Adfywiad

Mae’n fendigedig gweld fod yr arfer o glapio wedi ei adfywio bellach ar Ynys Môn ac felly, mae’n debyg am un wythnos o'r flwyddyn, unwaith eto yng Nghymru, mae’n ddiogel ac yn dderbyniol i roi eich holl wyau yn yr un fasged!