Scientific expedition to Rara Lake, Nepal

, 19 Mai 2016

Kathmandu University, Norwegian University of Life Sciences and National Museum of Wales

Dr Ingrid Jüttner, Principal Curator Botany, has studied the biodiversity of diatoms, a group of microscopic algae, in the Nepalese Himalaya since the early 1990s. In spring 2016 she was invited by her colleagues from Kathmandu University to join their team on an expedition to Rara Lake, a protected Ramsar wetland in the high Himalaya.

Here is her blog about the visit and scientific work on Nepal’s largest lake in the remote mountains of north-western Nepal.

23 April. In the morning our team met at Kathmandu Airport to take a flight to Nepalgunj, a town in the lowlands of western Nepal. The following day we flew with a small aircraft from Nepalgunj into the mountains of the Mugu district in north-western Nepal.

Our team was led by Dr Roshan M. Bajracharya, the project coordinator of the 5-year SUNREM-Himalaya Project at the School of Science, Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Kathmandu University. This project is funded by NORHED, the Norwegian Research Council, with a grant held by the Norwegian University of Life Sciences in Ås (NMBU), under the leadership of Prof. Bishal K. Sitaula, International Environment and Development Studies (Noragric).

The aim of our expedition was to investigate Rara Lake, to learn about its history, water quality and how the lake relates to its surroundings. We studied sediments, soils, microscopic algae and water chemistry. This will help us to understand how Rara Lake may be affected by climate change and local human activities.

Our team included eight researchers, Prof. B.K. Sitaula from Norway, Prof. R.M. Bajracharya, Dr Chhatra Mani Sharma, Dr Smriti Gurung, Dr Nani Raut, two master students Anu Gurung and Preety Pradhananga from Kathmandu University, and myself.

Rara Lake is the largest lake in Nepal with a 10.8 km2 surface area, a maximum length and width of 5 and 3 km, respectively, and a maximum depth of 167 m. It is situated at 2990 m altitude in the Rara National Park of the Mugu district in north-western Nepal.

The lake drains to the Mugu-Karnali river system via the Nijar Khola. Rara Lake is surrounded by conifer forest, dominated by blue pine associated with several species of Rhododendron, and by alpine meadows. The National Park is home to over 50 species of mammals, including the Himalayan Black Bear and the Red Panda, and to 272 bird species, with the lake itself being important for migrating birds. The lake is also home to three trout species, one of which is endemic.

The area is sparsely populated, but a small settlement including a guesthouse, a health post and an army camp are located at the northern lake shore.

24 April. After a 45 minutes flight from Nepalgunj with spectacular views of Rara Lake from the air our small plane landed at an airstrip in the village of Talcha at 2700 m altitude. From there we walked four hours to the lake.

25 April. The aim of this year’s field visit was to resurvey all sites which were first studied in October 2015. The sites were located in the lake littoral along the entire shore, and also included a number of small inlets and the outlet.

Diatom samples were taken at each site from all available substrata to study diversity and species composition in relation to water chemistry and habitat character. The collections from October and April will enable us to investigate possible seasonal differences between the post-monsoon season in the autumn and the pre-monsoon season in spring.

Physico-chemical parameters including temperature, pH, conductivity, turbidity were measured and water samples were taken for chemical analysis of nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphate, major ions such as silica, sodium, calcium and trace elements. Habitat features such as substratum composition and land use were recorded.

Today we started our field work exploring the north-western shore of the lake and the area near its outlet.

26 April. Four members of our team rowed across the lake to take bathymetric measurements and to locate the deepest part of the lake in preparation for the collection of sediment cores on the following days. A large deep basin with a maximum depth of 167 m is present in the western part of the lake, the area most suitable for coring.

The other team members walked around the entire lake while taking diatom, water and soil samples along the southern shore. The soil investigations included studies of four transects with four sites per transect located along altitude gradients. Soil samples were collected to study physical parameters such as bulk density and texture, chemical parameters including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, organic carbon, pH and cation exchange capacity, and the soil fauna.

After ten hours we arrived back at the guesthouse, it took us approximately seven hours to walk around the entire lake during which we stopped at several sites to collect our samples.

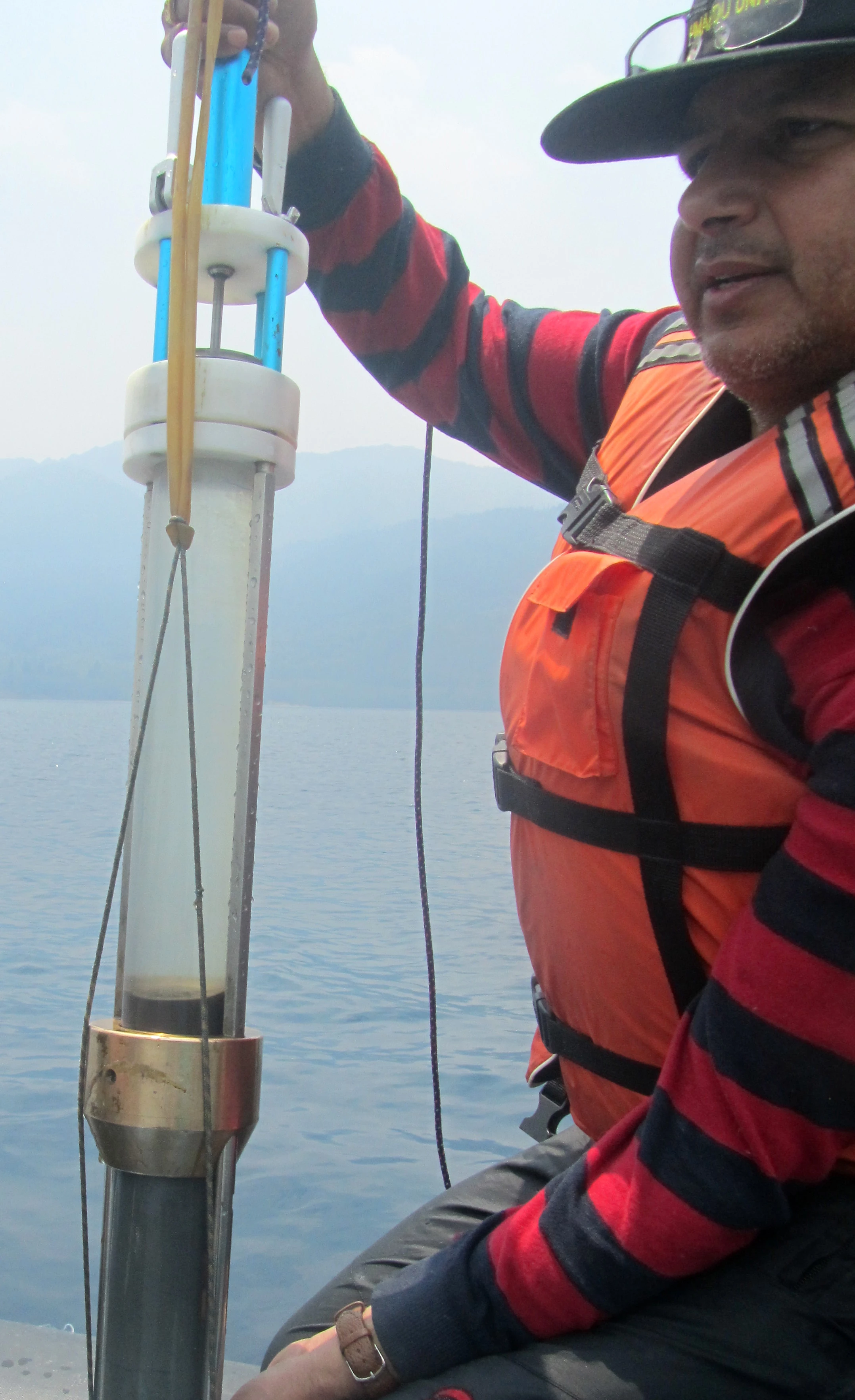

27 April. The morning was taken up by sediment coring which had to be completed by lunch time: in the afternoon the winds are too strong and the waves too high to keep the boat steady in one place. The army camp near our guesthouse provided us with a large inflatable boat and four soldiers to row it.

Lake sediment records contain remains of organisms and persistent chemicals which can be used to reconstruct environmental change over a period of time. Two 30 cm long sediment cores were extracted from a depth of 165 m. One of the cores was cut into 0.5 cm slices and will be used for dating. The second core was cut into 0.5 cm slices for the top 10 cm, and subsequently into 1 cm slices. Diatom assemblages will be investigated in each slice. Any major change in species composition along the core’s profile would indicate environmental change within the lake and in its catchment.

In the afternoon diatom and water samples were collected from several sites along the northern shore in the vicinity of the settlement and the army camp. It will be interesting to see whether negative impacts can be detected in this part of the lake due to polluting runoff.

28 April. In the morning three additional sediment cores were collected, and further bathymetric measurements taken in the eastern part of the lake. The cores will be analysed for trace elements, metals, nutrients and organic contaminants including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). After lunch we left the guesthouse to return to Talcha. On the way collections were made along one other soil transect, and water and diatom samples were collected from three sites on the north-eastern lake shore.

29/30 April/1 May. Since our arrival at Rara Lake mist had fallen and eventually was so dense that planes could not fly any longer into the mountains. We had to take a two day, 400 km long adventurous bus journey along a winding mountain road to return to Nepalgunj. In the evening of 1 May we arrived back safely in Kathmandu.

On 3 May I gave some lectures at Kathmandu University about freshwater algae including diatoms and my research projects in the Himalaya and the United Kingdom.

It was a wonderful opportunity to work together at Rara Lake, to complete our fieldwork successfully and report about my research on diatoms. Our project gave us reason for optimism, and the time spent together was uplifting and encouraging after the devastating earthquakes which hit Nepal in April and May 2015.