Digideiddio sbesimenau botanegol o Dde Asia ar gyfer y project Hawliau a Defodau

, 21 Chwefror 2023

Dros y 7 mis diwethaf mae curaduron wedi bod yn gweithio ar y project Hawliau a Defodau a ariennir gan Gyngor Ymchwil y Celfyddydau a'r Dyniaethau (AHRC). Nod y project yw gweithio gydag aelodau o'r gymuned leol i ail-ddehongli sbesimenau Botaneg o Dde Asia, o’r Casgliad Botaneg Economaidd yn bennaf, er mwyn darparu cyd-destun diwylliannol, deall dulliau traddodiadol o ddefnyddio cynhyrchion o’r planhigion ac er mwyn gwneud y casgliadau yn fwy hygyrch.

Mae'r Casgliad Botaneg Economaidd yn cynnwys tua 5500 o sbesimenau ac amrywiaeth o wahanol gynhyrchion o blanhigion, megis dail, gwreiddiau, ffibrau a hadau, ac mae gan bob un ohonyn nhw werth arwyddocaol yn economaidd, yn ddiwylliannol neu fel meddyginiaeth. Mae'r project hefyd wedi defnyddio casgliadau o sbesimenau llysieufa, darluniau botanegol, sbesimenau is-blanhigion a Materia Medica.

Mae digideiddio'r sbesimenau yn un dull allweddol o wneud y casgliadau yn fwy hygyrch, gan gynhyrchu delweddau y gellir eu rhannu â staff yr amgueddfa, gydag ymchwilwyr a gyda chymunedau y tu hwnt i'r amgueddfa. Defnyddiwyd sawl techneg i ddigideiddio'r sbesimenau, yn dibynnu ar eu maint a’u ffurf.

Mae'r Cynorthwy-ydd Ymchwil, Nathan Kitto, trwy gyfrwng amrywiol offer a thechnoleg, wedi adeiladu casgliad o dros fil o ddelweddau sy'n cynnwys taflenni llysieufa fasgwlaidd, sbesimenau mewn jariau a blychau, a darluniau hardd o waith llaw. Bydd y delweddau hyn yn cael eu storio yn llyfrgell delweddau ar-lein Gwyddorau Naturiol yr Amgueddfa, ynghyd â data’r sbesimenau, y gellir wedyn eu defnyddio fel adnoddau ymchwil a chyfeirio. Yn y dyfodol bydd y delweddau ar gael yn ehangach trwy gyfrwng Casgliadau Ar-lein yr amgueddfa

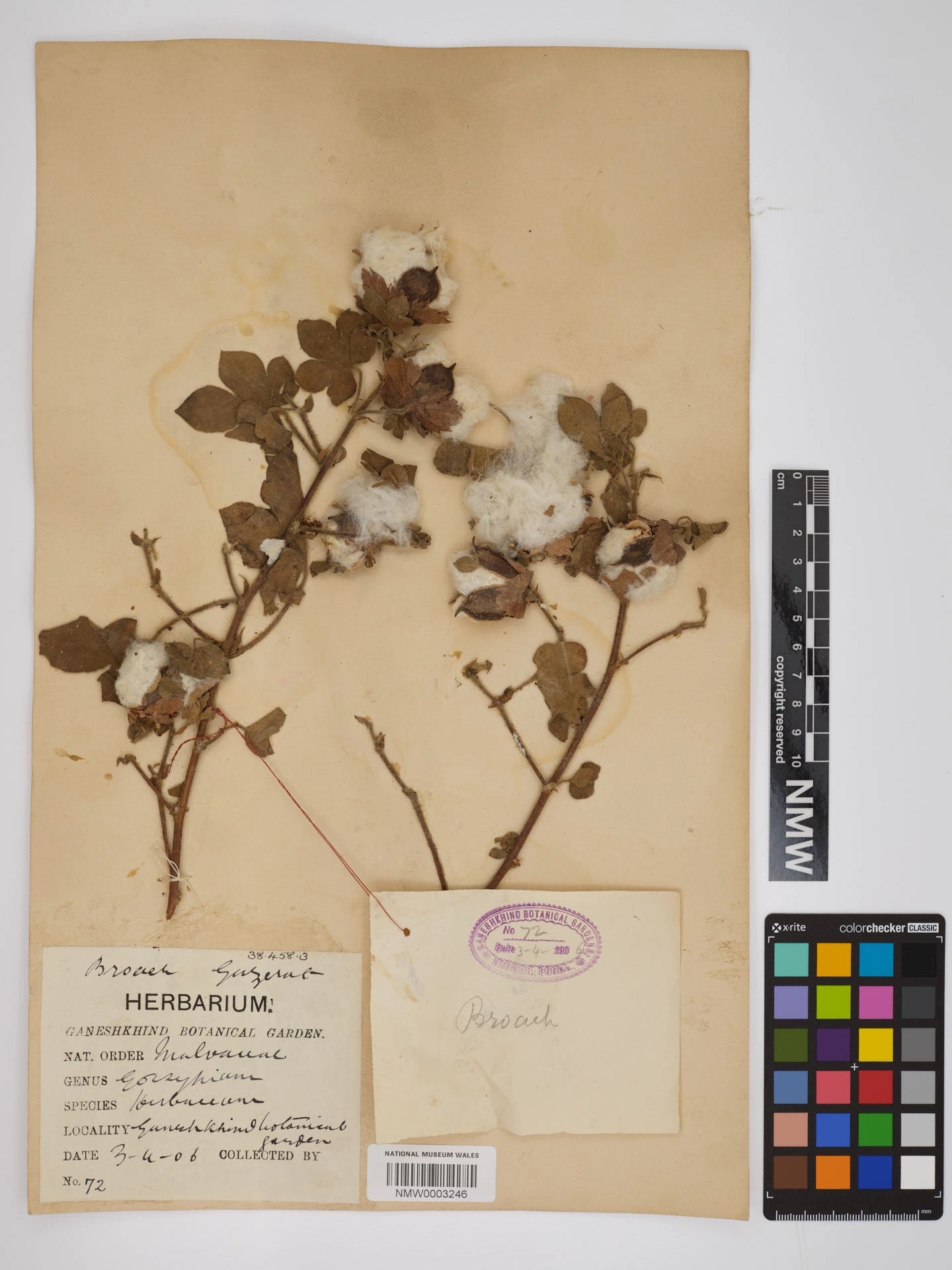

I ddechrau, crëwyd delweddau 2D gan ddefnyddio camera SLR digidol ansawdd uchel. Mae hyn yn gam hanfodol er mwyn cofnodi manylion unigryw’r sbesimen, gan gynnwys y rhif derbyn, enw cyffredin ac enw a tharddiad gwyddonol y rhywogaeth. Fel arfer, mae siart lliw yn cael ei gynnwys yn y ddelwedd er mwyn sicrhau cysondeb o ran lliw, maint a graddfa. Defnyddir offer micrograff hefyd i gymryd lluniau eithriadol agos o sbesimenau. Trwy chwyddo'r sbesimen, gellir gwahaniaethu manylion cain na ellir eu gweld fel arfer, gan roi dimensiwn hollol wahanol.

Yn ddiweddar, prynwyd offer sganio 3D uwch-dechnoleg newydd, diolch i grant gan AHRC. Mae sganiau 3D manwl iawn wedi'u cynhyrchu o rai sbesimenau penodol a oedd yn addas o ran maint a siâp. Mae'r offer yn ein galluogi i gymryd delwedd lawn 3D o sbesimen ac felly gall defnyddwyr terfynol gylchdroi'r sbesimen a’i weld o bob ongl, sy’n rhoi persbectif reit wahanol o gymharu â delwedd dau ddimensiwn.

Mae'r sganiwr yn gweithio trwy gymryd sawl ffrâm neu ddelwedd o'r gwrthrych o onglau gwahanol er mwyn adeiladu delwedd 3D go iawn. Mae gan un math o sganiwr, sef yr Artec Micro, broses fwy awtomataidd gyda'r offer yn gwneud y rhan fwyaf o'r gwaith, drwy gylchdroi a dewis onglau penodol i gymryd delweddau o ansawdd uchel. Ar y llaw arall, mae'r Artec Space Spider yn sganiwr llaw, sy’n cael ei reoli gan y gweithredwr. Mae’n cymryd mwy o ddelweddau wrth i’r gwrthrych gylchdroi. Roedd yn hawdd iawn i'w ddefnyddio ac yn gywir iawn hefyd. Ar ôl cael digon o ddelweddau o wahanol gyfeiriadau, mae’r delweddau’n cael eu cyfuno gan ddefnyddio meddalwedd Artec Studio arbenigol. Gydag ychydig o fireinio ac ail-leoli, mae model 3D yn cael ei greu a'i lanlwytho i Sketchfab. Dyma'r stiwdio ar-lein lle mae modd optimeiddio'r ddelwedd 3D o'r sbesimen gyda goleuadau a golygiadau safleol. Mae'r llyfrgell o ddelweddau Botaneg Economaidd 3D, sydd i'w gweld yma, yn dangos 21 model o sbesimenau, gyda gwybodaeth ategol am y modd y defnyddir y rhywogaethau unigol fel meddyginiaeth ac mewn diwylliannau traddodiadol.

Mae yna fanteision di-ri o gael modelau 3D o sbesimenau amgueddfa; maen nhw’n gwneud y casgliad yn hygyrch i bawb, ac yn addas ar gyfer chwiliadau ar-lein. Mae modd archwilio’r gwrthrychau’n fanwl heb gyffwrdd â’r sbesimen gwreiddiol nac achosi unrhyw ddifrod. Nid yw ased digidol yn dirywio dros amser a gellir ei gopïo a'i storio mewn sawl man a’i ddefnyddio hefyd i greu modelau printiedig 3D. Ar ben hynny, mae gwrthrych 3D digidol yn golygu bod modd rhyngweithio’n wahanol â’r gwrthrych.

Defnyddiwyd y modelau 3D i wneud sbesimenau’r Amgueddfa yn hygyrch i aelodau'r cyhoedd yn ystod gweithdai cymunedol. Cafwyd adborth cadarnhaol iawn yn sgil y math hwn o ymgysylltu a bu’n fan cychwyn da ar gyfer trafodaethau am gasgliadau’r amgueddfa a'r dulliau niferus o ddefnyddio'r sbesimenau. Ond y cam cyntaf yn unig yw creu'r modelau 3D hyn. Mae'r curaduron ar y project Hawliau a Defodau yn awyddus i weld sut bydd pobl yn parhau i ryngweithio â'r modelau yn y dyfodol ac yn gobeithio y bydd yn adnodd defnyddiol a deniadol i'r cyhoedd a'r amgueddfa ei rannu. Os oes gennych chi unrhyw sylwadau am y gwrthrychau sy'n cael eu dangos yn y blog hwn, cysylltwch â: heather.pardoe@amgueddfacymru.ac.uk.